The Lambeth Palace Apocalypse is an exquisite example among illuminated manuscripts focused on the Apocalypse, the description of events at the end of time by Saint John the Divine that forms the final book of the Christian Bible. Made in the 1260s probably in London, the manuscript takes its name from the Archbishop of Canterbury's palace in London. Seventy-eight half-page miniatures and occasional additional imagery in the bas-de-page illustrate the text of the Apocalypse. The manuscript is unique among illuminated Apocalypse manuscripts for its full-page frontispiece of a painter and its twenty-seven full-page miniatures on devotional themes.

The text includes excerpts from an eleventh-century commentary on the Apocalypse by Berengaudus that focuses on the dangers of sin. That commentary—together with the book's devotional imagery—made the manuscript a suitable manual for personal behavior for its patron, Eleanor De Quincy, Countess of Winchester (d. 1274), who is pictured in the manuscript.

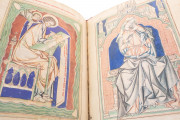

A Puzzling Frontispiece

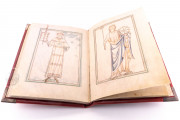

Opening the manuscript is a full-page portrait of a Benedictine monk in the process of painting a statue of the Virgin and Child that seems to be coming to life as he paints it. This image is perplexing both because it depicts a monk and because it alludes not to painting in a manuscript context but within the process of creating a devotional statue.

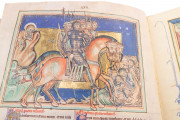

Powerful Imagery

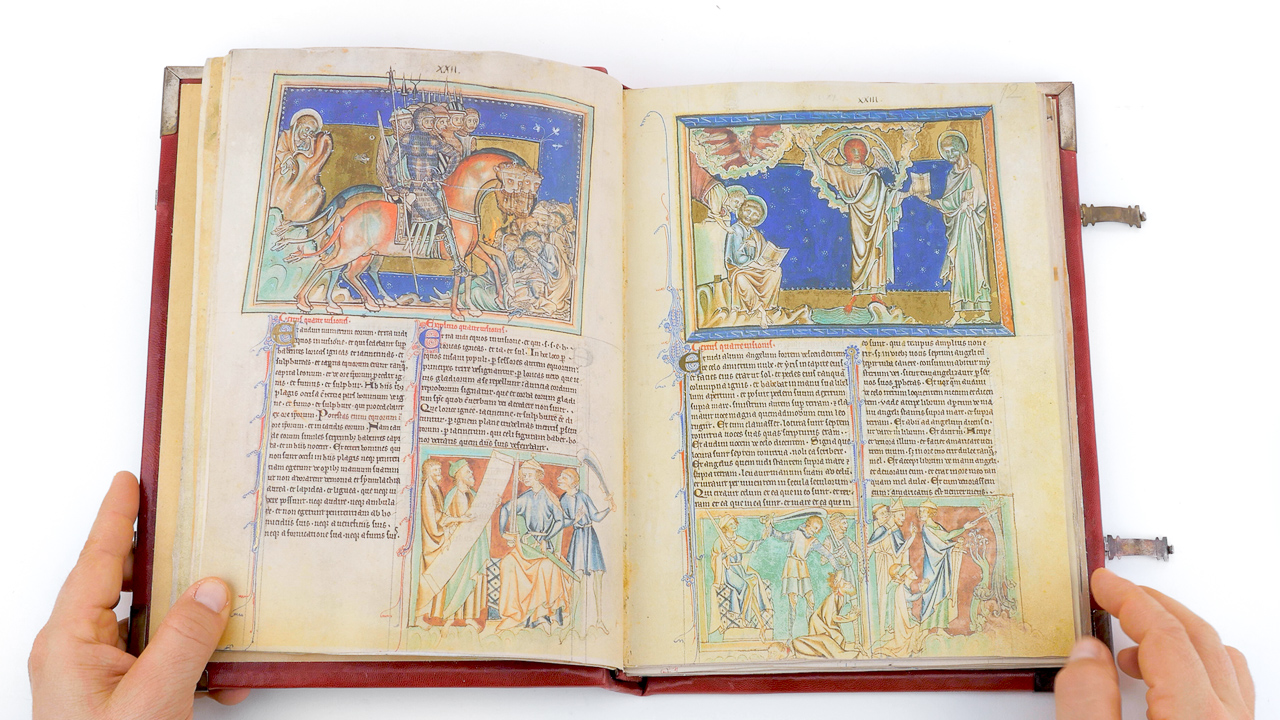

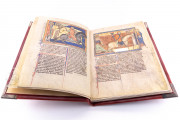

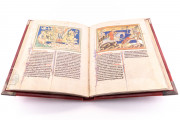

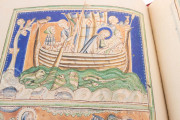

The top half of each page of the Apocalypse text and commentary is occupied by a framed miniature that illustrates the text below. The miniatures are dominated by terrifying scenes of earthly destruction and images of unearthly beasts, such as a seven-headed horned dragon and a multi-headed spotted beast. Saint John himself is sometimes shown experiencing his vision either in the miniature or looking in through a fictive window in the frame.

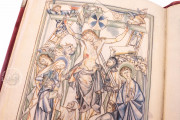

A Devotional Turn

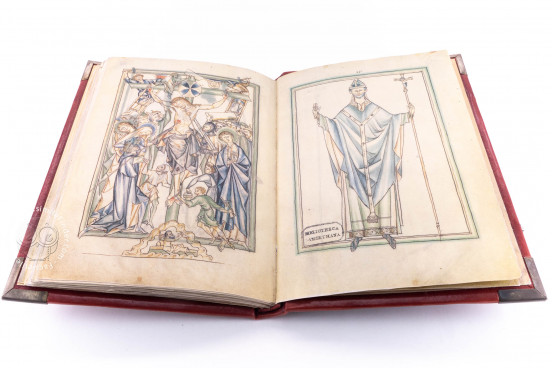

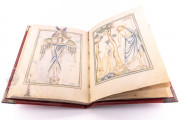

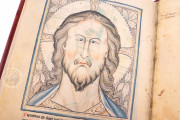

Following the illuminated text of the Apocalypse, the manuscript features a series of full-page miniatures starting with scenes from the life of Saint John the Evangelist, understood in the Middle Ages to have been the author of the Apocalypse. There follow miracle scenes and devotional images, including a Crucifixion. On the last page is pictured the holy face of Christ, according to legend imprinted on a cloth used by Saint Veronica to wipe the sweat from Jesus's brow as he carried the cross to the Crucifixion.

Tinted Drawing Technique

The illuminators of the Lambeth Apocalypse rendered figures in the tinted drawing technique popular in England at the time. Among the full-page miniatures, the figures usually appear on unpainted parchment. In the Apocalypse scenes, by contrast, the figures drawn with washes of color appear against backgrounds of gold and vivid colors.

The artists of the Lambeth Apocalypse were responsible for the illumination of two other Apocalypses, the Gulbenkian Apocalypse and the Abingdon Apocalypse (London, British Library, MS Add. 42555).

At Least Three Scribes

The text, in two columns, was written by at least three scribes in Gothic Textualis script. Each segment of the Latin text of the Apocalypse and the commentary is introduced by a pen-flourished initial. Some of the miniatures feature inscriptions, either in Latin or Anglo-Norman, the French spoken in England.

To Cambridge and Back

The manuscript, once owned by John Lumley (d. 1609), entered the library of Lambeth Palace in the first half of the seventeenth century. Under the Commonwealth (1649 to 1660), the manuscript was transferred to Cambridge University Library, and it returned to Lambeth in 1664, after the restoration of the monarchy. Its current binding, of black morocco by Eyre and Spottiswoode, dates from the nineteenth century.

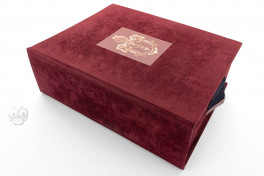

We have 2 facsimiles of the manuscript "Lambeth Palace Apocalypse":

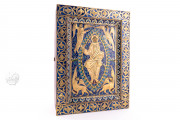

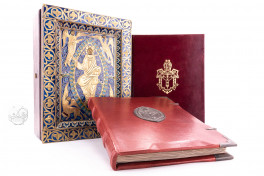

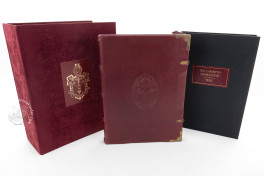

- Die Lambeth Palace Apokalypse (Deluxe Edition) facsimile edition published by Coron Verlag, 1990

- Die Lambeth Palace Apokalypse (Standard Edition) facsimile edition published by Mueller & Schindler, 1990