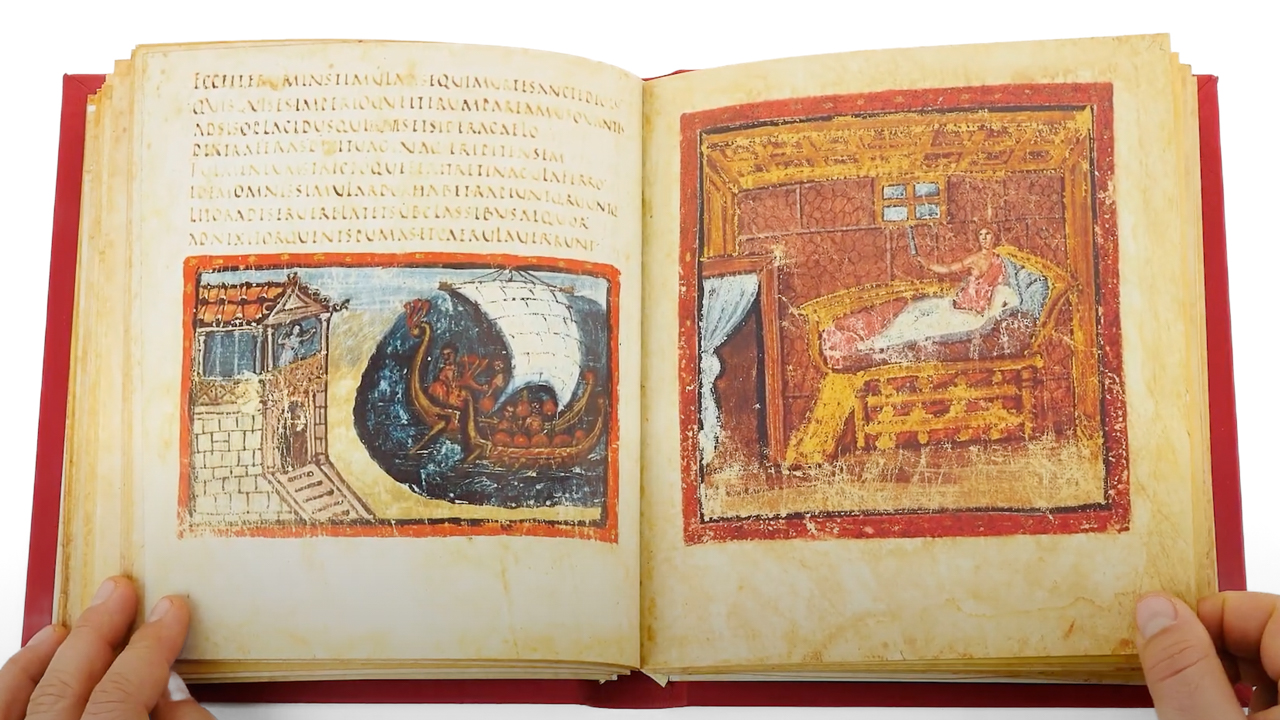

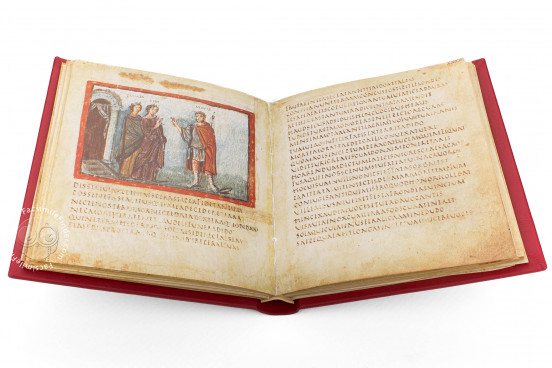

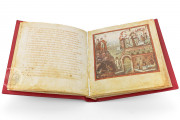

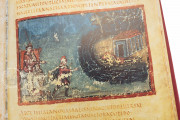

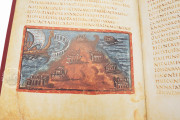

A rare survival from the dawn of the literary codex, the Vatican Virgil, also known as Vergilius Vaticanus, is the preserved portion of an illuminated copy of the major works of the ancient Roman poet Virgil. Made in Rome around 400, it was probably created for a wealthy aristocrat who wanted a copy of the centuries-old works of the golden age of Latin literature using the prevailing book technology and artistic style of the late imperial period. Fifty miniatures are preserved, about one-fifth of the original total.

The manuscript was enormously influential in the Middle Ages and the early modern period, with artists studying and copying its compositions from the ninth to the sixteenth century. The style of its miniatures, especially the atmospheric backgrounds composed of horizontal striations of color, also inspired artists.

Three Artistic Personalities

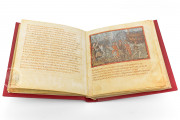

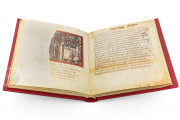

The surviving Latin text is, unfortunately, incomplete. Of the original 440 leaves, only seventy-five remain with fragments of the Georgics and the Aeneid. Most surviving leaves have half- to full-page miniatures.

Three artists worked on the book. The illustrator of the Georgics is an accomplished painter: his figures are well modeled, and he employs delicate shading (nine of the surviving miniatures). The work of the second painter, who illustrated portions of the Aeneid, appears hurried, with bold outlines and little shading. His are some of the best-preserved miniatures (sixteen extant). The third artist demonstrates an eye for detail and a good understanding of the human body (twenty-five of the surviving miniatures).

Modernization of the Revered

The codex form (a book of folded sheets sewn at the spine, with pages that can be turned) was introduced in the Roman imperial period, replacing the papyrus roll as the usual medium for literary works. The creators of the Vatican Virgil were probably copying both text and images from older models in roll form. The codex format and the parchment support, however, allowed the artists to use more paint, provide painted frames, and render atmospheric backgrounds.

The manuscript’s pages are nearly square in proportion, a characteristic feature of early codices. A single scribe copied the text in Rustic Capitals, the script customarily used for literary works in the late imperial period. There is no spacing between words.

From Rome to Tours and Back Again

The manuscript remained in Rome until at least the sixth century when some of the poetic text and the picture inscriptions were retraced. By 840 it was at the collegiate church of Saint-Martin in Tours, possibly bequeathed by the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne (742-814). At this time, the book was mostly intact. The fate of the book is then untraced until the fifteenth century, by which time it seems to have suffered its losses.

By 1514, it was certainly back in Rome, where it served as a model in the artistic circle of Raphael (1483-1520). Pen and wash copies of the surviving paintings were made in the early sixteenth century (Princeton, Princeton University Library, MS 104). The Venetian scholar Pietro Bembo (1470-1547) acquired the manuscript by 1521. His son, Torquato Bembo (1525-1595), sold it to the bibliophilic humanist Fulvio Orsini (1529-1600), who bequeathed it to the Vatican.

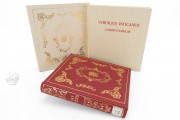

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Vatican Virgil": Vergilius Vaticanus facsimile edition, published by Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt (ADEVA), 1980

Request Info / Price