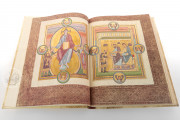

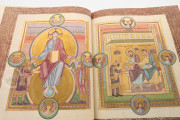

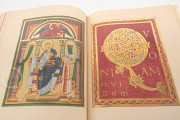

One of the greatest treasures of the University Library of Uppsala, the Codex Caesareus, is a Gospel book commissioned by the German Emperor Henry III for the Goslar minster. One of the opening pages of the manuscript indicates the purpose for which it was originally created: the miniature on fol. 4 shows Emperor Henry III presenting the book to the Apostles Simon and Jude, patrons of a new church built in front of his palace in Goslar.

Even if the dedication miniature in the Uppsala Gospels bears the inscription MXLV in a frame on the top medallion above the church, the date has only a symbolic meaning: Henry III had not yet decided to build a new church. The idea of a church added to the royal residence in Saxony may have come to him during a visit to Italy in 1046, when he received the Imperial Crown in the Basilica of St. Peter.

A charter from 1049, signed by Pope Leo IX, attests that the Emperor had placed the new church under the protection of the papal charts at the time, and that he had taken the role of guardian-controller (a special form of Western Caesar-papism). New legacies in favor of the Church were recorded in 1050, and the inauguration took place on July 2nd, 1051 by the Archbishop Heriman of Cologne, one of the Emperor's most trusted collaborators.

A Jewel of the Echternach School

Scholars generally recognized that the book was produced in the monastery of St. Willibrord at Echternach. The Abbey of Echternach, situated in present-day Luxembourgh on the banks of river Sauer, traces its origins back to the Anglo-Saxon missionary Willibrordus, who came from Northumbria to continue spreading Christianity among the Frisians.

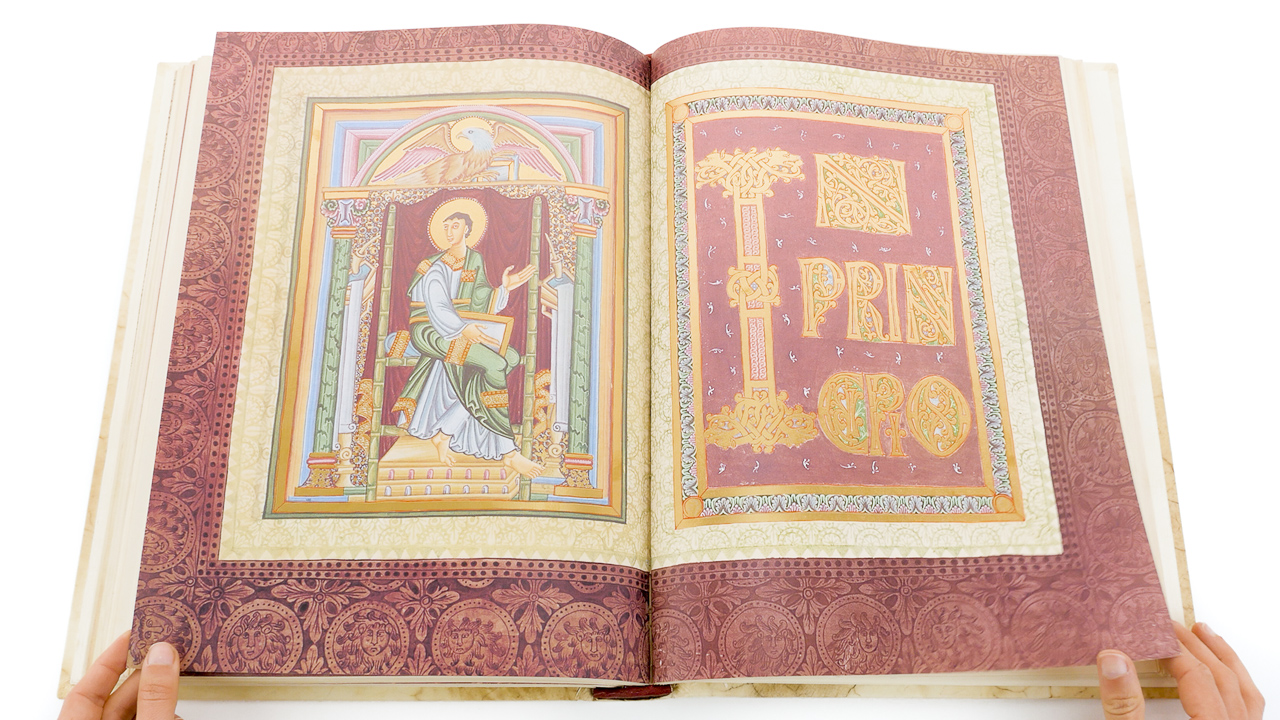

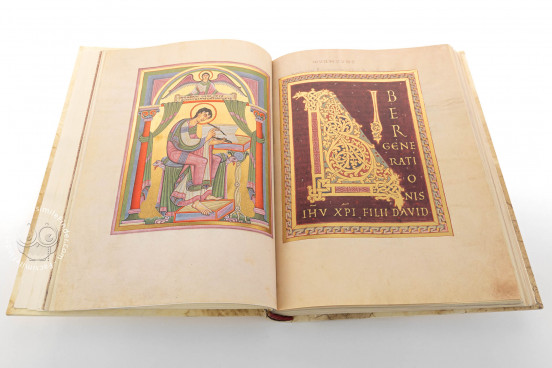

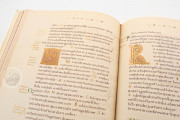

The Uppsala Gospels is one of the seven Gospel-books written in Echternach during the second and third quarter of the eleventh century. One of the characteristics which immediately catches the eye is its truly royal size (about 38 x 28 centimeters), being among the largest ever produced by the Ottonian School. The parchment is of very fine quality, being white like ivory in the manner of the Echternach Gospel-books.

The chronological sequence in which the Echternach manuscripts can be put according to the stylistic development of their full page initials has an inner logic of its own and cannot be reversed or changed at any point.

The painter of the Uppsala Gospels seems to have had the Speyer page still in mind when he designed his In principio composition. The codex takes its place between The Speyer Gospels, or Codex Aureus Escurialensis (completed shortly before Henry III travelled to Italy in the fall of 1046), and the Harley MS 2821 in the British Library.

The Uppsala codex was probably produced during the abbacy of Humbert, who died in 1051.

A Transitional Gospel-book

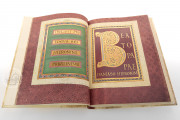

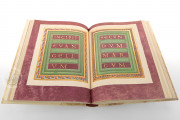

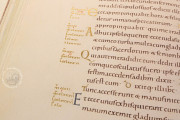

Before the large format was abandoned, there was, in the Uppsala Gospels, a shift from two columns to one, with 31 lines to a page, written in a Carolingian minuscule of great clarity and legibility.

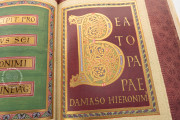

The Gospels were written in brownish-black ink, which sometimes shows considerable variation in hue. The initial letter of each sentence and the colophons were filled with gold or color, the smaller capitals inside the text columns and the rubrics were always written with gold.

Punctuation is simple: a dot, mostly placed slightly above the line, marks the end of a sentence, also where commas would be used. Only one scribe penned the Gospels, likely Echternach scribe B.

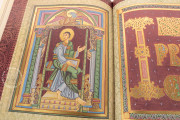

Late-Ottonian and proto-romanesque miniatures

Opposite the picture of Christ in Majesty crowning Henry III and his consort, a second full-page miniature portrays the Emperor alone presenting the Gospel-book to St. Simon and St. Jude. The two miniatures form a pair: the scene on the left shows the solemn confirmation of the Emperor's investiture by the coronation in Rome, and on the left Henry III is presented with his most venerable outfit, the Holy Writ.

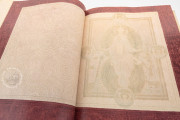

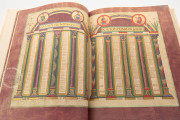

The elaborate full-page textile ornaments are reduced to the two at the beginning of the manuscript, witnessing the transition from the tradition of royal-size books – with several double textile pages – to smaller Gospel-books. However, many purple margins are decorated with textile patterns, in a contrasting network of green lines against white, to emphasize the most relevant miniatures.

Scholar Albert Boeckler recognized three different hands. To the first artist he gives the portrait of St. Matthew – Master of St. Matthew –, to the second – the Master of the Mutineers –, the other three evangelists, and the Canon tables, and to the third, the two frontispiece miniatures – Maiestas Domini and the Dedication Scene.

The miniatures of the Uppsala Gospels are still of imposing grandeur but witness a tendency towards greater rigidity of all forms, typical of the second half of the eleventh century.

A Story That Crosses Europe

Having been presented to the church of St. Simon and St. Jude in Goslar, the Uppsala Gospels entered a second phase of its history which consisted mainly of standing in continuous danger of being stripped of its precious binding, as recorded first in a document dated between 1174 and 1195 concerning possessions of the Goslar Cathedral.

The accepted idea is to connect the abduction of the Codex Caesareus from Goslar and its reappearance a century later in the hands of a Swedish nobleman and collector, with the occupation of Goslar by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years War. No documentary evidence proves that the Gospel-book came to Sweden in the 1530s, by which time the book had already lost its jeweled cover.

The name of the first known owner – Gustavus Petri Celsing – appears on the top of the first page in Latin, followed by other inscriptions in Slavic, Russian or perhaps Cyrillic. Celsing served under King Charles XII in his campaign against Peter the Great of Russia, and then travelled throughout Turkey and the East before returning to his hometown.

There he came into contact with the chief librarian of the Uppsala Academy, Eric Benzelius. In a letter, dated April 7th, 1740, the book is presented by Benzelius as the Gospel-book by the German Emperor Henry II. After the death of Celsing, the codex remained in the possession of his heirs, while most of the books in his collection were sold at auction. His son, Ulrik left the Codex Caesareus to the University Library in Uppsala in 1805.

Binding description

Binding

The original binding made of gold and precious stones was replaced by a simple blue velvet coating of Italian origin, with five silver rosettes, some time after 1632–1634. The Codex still bears the oak boards of its original medieval binding. The front board in particular presents a central rectangular recess and holes that suggest a metal ornament, possibly decorated with a cross.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Uppsala Gospels": Codex Caesareus Upsaliensis facsimile edition, published by Almqvist & Wiksell, 1971

Request Info / Price