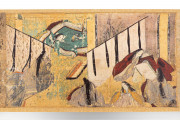

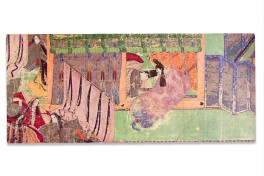

Composed in the twelfth century, the Tale of Genji Scroll (Gengi Monogatari Emaki) is the oldest extant example of monogatari emaki ("illustrated narrative handscroll") in Yamato-e style. The scroll illustrates and explains the plot of the Tale of Genji, a classic eleventh-century Japanese narrative set in the courts of the Heian period and written by the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu. The emaki is a form of pictorial art unique to Japan, consisting of "explanatory comments" (kotobagaki) on the narrative followed by an illustration similar to an independent painting that depicts the scene described by that textual passage.

The Gengi Monogatari Emaki, also known as Takayoshi Genji, spans a total of twenty pictures including detached fragments. At the time when Murasaki Shikibu was writing the Tale of Genji, Japan's aristocratic society was enveloped in the doctrine of Pure Land Buddhism—its visual depictions were viewed as "splendid illustrations" that had to adopt the form of an illustrated handscroll capable of evoking the Pure Land Paradise in the viewer's imagination.

The Flourishing of Elegance and Stillness

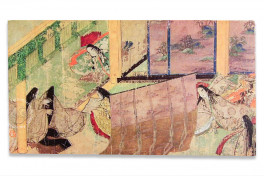

Yamato-e painting employs the painting process of tsukuri-e, the style of onna-e, and the dan'raku format of independently depicted scenes. Tsukuri-e refers to the process that begins with "line-drawing in black ink" (sumigaki) to determine the scene and layout, proceeds to the application of layers of pigment on the painting surface and the arrangement of patterns, and ends with the final painting of details. Onna-e consists of illustrations that depict women and evoke a sense of elegance.

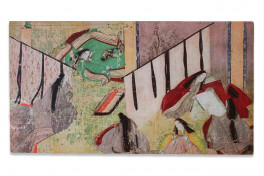

The compositional techniques of the Tale of Genji Scroll condense the authorial intent, through pictorial art, into an optimal expression of elegance and stillness. If portrayed from a side position, the main characters would be invisible, concealed by bamboo blinds or by screens. For this reason, the painters adopted a bird's-eye view composition with a diagonal perspective.

When an indoor scene is portrayed from the perspective of such illustrations, however, the view is completely blocked by the roof. Painters thus fabricated access by eliminating such visual barriers as the roof, ceilings, and occasionally even the head jamb.

Faces are portrayed as "white in the shape of melon seeds" (urizanegao) with a wide forehead. The eyebrows are drawn by overlapping many thin, straight lines, the nose is drawn as a hook shape, and the mouth is indicated by a red dot. This totally deindividualized and unrealistic method of facial representation allows readers to freely project their personal longings onto the illustrations and thus satisfy their imagination.

Appraisers in the Edo period identified the painter as Fujiwara Takayoshi or Takachika and the kotogabaki writers as Asukai Masatsune, Sesonji Korefusa, Jakuren, and others, but these appraisals were not based on historical documents.

The Importance of Form and Beauty

The elaborately crafter calligraphy, penned on luxuriously ornamented paper flecked with gold and silver leaf uses diverse techniques, such as "scattered writing" (chirashigaki), "continuous and floating threads" (remmen yūshi), "indentation" (dan'otoshi), and "overlapped writing" (kasanegaki).

The explanatory comments (kotobagaki) and calligraphy were designed not for reading, but for the primary aim of appealing to the eye through formative beauty. The first sheet of each chapter is decorated to allude metaphorically to the chapter's main theme and ends in a waka (a Japanese poem in thirty-one syllables) that lingers to arouse the viewer's imagination.

An Intricate History

The extant sections, consisting of 65 sheets of text, 19 paintings, and 9 pages of fragments, represent about 15 percent of the original artwork. The surviving sections, kept in Gotoh Museum in Tokyo and the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya, were originally part of a 450 feet long scroll containing over 100 paintings and more than 300 sheets of text.

The three Tokugawa-bon scrolls are thought to have been handed down from the Owari branch of the Tokugawa family who obtained them in the early years of the Edo period (1603-1868). In 1931, the scrolls were donated to the Owari Tokugawa Reimeikai Foundation and, after rearranging them according to the correct sequence, presented to the Tokugawa Art Museum.

Historical documents confirm that, in 1849, the single Gotoh-bon scroll was in the possession of the Hachisuka family, who ruled both the Awa and Awaji provinces, but do not explain when that family first acquired it. In the late Meiji period, it became the property of Masuda Takashi and was subsequently known as the Masuda-bon. The scroll was donated to the Gotoh Museum, founded in 1960, and subsequently renamed the Gotoh-bon.

We have 2 facsimiles of the manuscript "Tale of Genji Scroll":

- Genji Monogatari Emaki facsimile edition published by Maruzen-Yushodo Co. Ltd., 2003

- Die Geschichte vom Prinzen Genji facsimile edition published by Mueller & Schindler, 1973