During their pilgrimage to Jerusalem, many pilgrims succumbed to sunstroke, thirst, and attacks from bandits and non-Christians, losing all their possessions. Those who fell ill were often left behind by fearful companions. Additional threats included wild animals, injuries, and diseases. In response to these dangers, eight knights led by Hugues de Payens vowed to protect these travelers. Around 1118, they founded a chivalric order known as the "Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ." King Baldwin II of Jerusalem provided them with a residence within the Temple of Solomon, earning them the name "Templars."

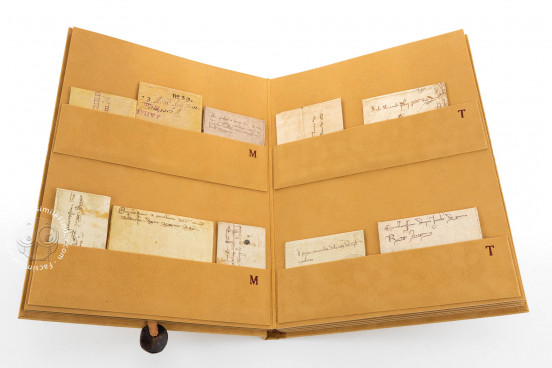

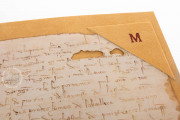

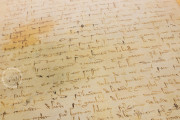

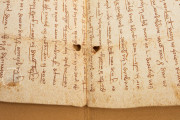

Original Rule of the Templars

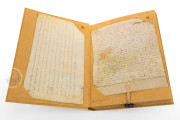

Initially independent, the order received papal endorsement at the Council of Troyes in 1128. Pope Honorius II approved their rule, crafted by Bernard of Clairvaux, and bestowed legitimacy upon them. However, the Templars encountered a challenge: the Original Rule was penned in Latin, which many members, primarily soldiers rather than clerics, could not read. Consequently, it was translated into French for the significant contingent in France.

The Original Rule detailed their monastic duties, attire, hierarchy, and allowed possessions, including servants and horses. It also outlined conduct during peaceful times, decision-making by elders, penances, and offenses leading to expulsion. The rule was kept in the Departmental Archives of Côte D’Or until it was stolen in 1985, though a microfilmed copy was preserved.

Rise and Expansion

The Templars rapidly gained influence, becoming trusted advisors in major political matters and local disputes. By the 13th century, their order had burgeoned to over 15,000 knights and controlled around 9,000 castles and fortresses. Despite vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience, their power and wealth sparked fear among monarchs. Rumors circulated about their political ambitions.

King Philip IV of France, financially strained and indebted to the Templars, saw an opportunity in the controversial practices of the order. The Templars’ attempts to bridge Christianity with other religions were met with disapproval by the Church. Additionally, their secretive initiation rites fueled suspicion.

Trial of the Knights Templar

On October 13, 1307, Philip, with Church approval, arrested many Templars, who were tortured into confessions. This marked the beginning of the order's downfall. Jacques de Molay, their last Grand Master, was captured and spent almost seven years imprisoned before being executed.

At the castle of Chinon, de Molay and other knights awaited a papal intervention that never came. They were accused of heretical practices, such as obscene initiation rites and disrespecting Christian symbols.

Even though a papal commission absolved them in 1308, Philip IV continued his pressure, and in 1312, Pope Clement V dissolved the order.

The Templars' tragic end came with the execution of Jacques de Molay on March 18, 1314, in Paris, marking the fall of one of history’s most enigmatic orders.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Secretum Templi (Collection)": Secretum Templi I facsimile edition, published by Ediciones Grial, 2005

Request Info / Price