The Old English Illustrated Hexateuch is a copiously illustrated manuscript of a paraphrase in Old English of the first six books of the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. Copied and illuminated at the Benedictine abbey of Saint Augustine's at Canterbury, it boasts 394 miniatures with more than 500 scenes illustrating the biblical text, an early medieval biblical picture cycle of enormous scope. The preface and the opening twenty-two books of Genesis are the work of Ælfric, Abbot of Eynsham, a prolific writer of Christian texts in the vernacular.

The manuscript's illumination is unfinished, providing a fascinating glimpse into the working methods of early English illuminators. Even in its unfinished state, the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch is one of the most important literary and artistic survivals from England before the Norman Conquest.

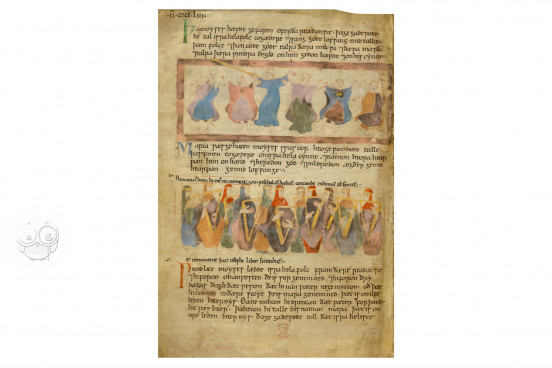

Visualizing Moses

The miniatures chronicle the history of Creation, the Jewish patriarchs, the prophet Moses, and Moses's successor—Joshua. The manuscript includes the earliest representations of Moses with horns, as suggested by the Latin Bible, which renders the Hebrew description of Moses's face as having rays of light when he descends from Mount Sinai into cornuta esset facies ("his face was horned"; e.g., fol.105v).

The first surviving depiction of the implement with which Cain kills his brother Abel, an animal jawbone, is found in the Hexateuch (fol. 8v). There is evidence, although it is debated, that some of the details in the book's miniatures were inspired directly by the Old English text.

Extra-Biblical Subjects

While most of the miniatures illustrate the biblical text, some subjects are without foundation in the Bible. These include the Fall of the Rebel Angels (fol. 2r) and the archangel Michael teaching Adam to work the earth (fol. 7v).

The Script of Old English

The manuscript was written by two scribes in long lines (a single column) in the customary script for writing Old English, English Vernacular Minuscule. There is no consensus concerning the number of painters involved in the manuscript's production, whether one or several. There is no doubt, however, that the miniatures were—contrary to usual practice—sketched out before the text was written.

New Interest in the Twelfth Century

A series of more than 300 notes in Latin and Old English was added to the manuscript in the second half of the twelfth century. These provide commentary and supplemental text, including extracts from the Historia scholastica, a Latin paraphrase of the Bible by the French scholar Peter Comestor (d. 1178).

New Interest in the Sixteenth Century

The first recorded modern owner of the manuscript is Robert Talbot (d. 1558), who transcribed its text in one of his notebooks. By 1621, it was in the collection of Robert Cotton (1571-1631). It was bequeathed to the British nation by Robert's grandson John Cotton (1621-1702) and formed part of the British Museum library's foundational collection in 1753. It was transferred, as were most of the manuscripts in the British Museum's collection, to the British Library in 1973. The current binding of green calfskin dates from 2006.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Old English Illustrated Hexateuch": Old English Illustrated Hexateuch facsimile edition, published by Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1974

Request Info / Price