The Diary of Murasaki Shikibu is a striking example of emaki, a Japanese illustrated scroll, composed in the mid-thirteenth century and inspired by the diary of Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court during the Heian period (794-1185). In its present form, the Diary of Murasaki Shikibu consists of twenty-three text passages and twenty-four illustrations in the classical Japanese yamato-e style; it takes the form of three handscrolls, six framed pages, and two hanging scrolls, currently stored in six different collections in Japan.

The Diary of Murasaki Shikibu begins with a series of magnificent descriptions of ceremonies celebrating the birth of Princes, but then her pen starts to drift off in a different direction, and as she begins transcribing her thoughts we realize that this diary is, in fact, speaking to us of the deeply personal feelings, inner agonies, and sorrows of a lady-in-waiting in service at a court.

The Charm of Bold Outlines and Acute Angles

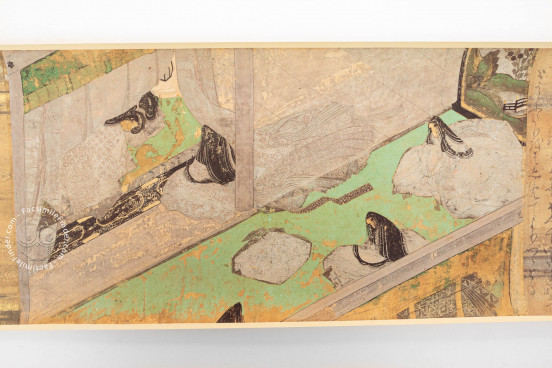

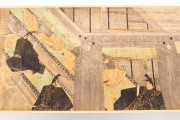

The illustrations favor deep colors and often use the "building-up" technique of tsukuri-e, in which colors are painted over an outline done in black ink and people's faces and the patterns on clothing are added afterward. In general, the illustrations tend heavily towards explaining the text passages, making them both easy to understand and light on symbolism. In most of the illustrations the pictorial technique involves the use of crisscrossing diagonal lines, a style known as naname kōzu, "diagonal composition", in which both the width and the depth of a building are represented diagonally.

The work's decoration, which relies for the most part on the pictorial technique of tōjikusokutōei—a method characterized by its acute angularity and its refusal of horizontal lines—features startling compositions in which buildings cut into the picture from the right and the left, the top and the bottom; the freshness and the inspired feel of these compositions have much to do with the charm of the work.

The picture is divided up into basic forms defined by acute angles; straight lines and curves are set in contrast with each other, as are colors, which are used very effectively to accent certain aspects of the images; and human figures are presented with simple clarity through strong, clear outlines, with their upper and lower eyelids drawn in, and so on.

It seems likely that the style in which these human figures have been depicted gave rise to the traditional attribution of the paintings to Fujiwara no Nobuzane, who was a master painter of portraits.

A Renowned Poet as Calligrapher

From the Edo period on, the twenty-three text passages of The Diary of Murasaki Shikibu Illustrated Handscroll were attributed to Gokyōgoku Yoshitsune (1169-1206), who wrote over 1600 poems at the end of the Heian period. The calligraphy of the text passages is the same in all four scrolls, pointing to the fact that these four illustrated handscrolls originally constituted a single set.

The Wishes of a Japanese Regent

Consideration of the style of the illustrations and the calligraphy used in the text passages, as well as of the way in which the paper itself is decorated, suggests that The Diary of Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Ekotoba was produced in the second or third decades of the thirteenth century.

The sequence of the Diary of Murasaki Shikibu Illustrated Handscroll as it exists today is considerably confused: it is thought that the work came to be divided up amongst the Hachisuka, Akimoto, and Matsudaira clans sometime in the first half of the seventeenth century.

The art historian Minamoto Toyomune has argued that the production of the handscroll was overseen by the regent (kanpaku) Kujō Michiie (the son of Gokyōgoku Yoshitsune, lived 1193-1252) when his daughter, Empress Shunshi, gave birth to a prince by Emperor Go-Horikawa in the third year of the Kanki era (1231).

He suggests that Michiie decided to have The Diary of Murasaki Shikibu made into a handscroll because, hoping to see his daughter Shunshi become Mother of the Realm (kuni no haha) and to see his family's fortunes prosper, he turned a worshipful gaze back to the auspicious precedent of Empress Shōshi, who had mothered two emperors.

The work is currently stored in six different locations: the Gotoh Museum in Tokyo, the Fujita Art Museum in Osaka, Tokyo National Museum and three private collections.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Ekotoba": Murasaki Shikibu Diary Emaki facsimile edition, published by Maruzen-Yushodo Co. Ltd., 2004

Request Info / Price