The Book of the Usefulness of Animals (Kitāb manāfi' al-hayawān) is an illustrated Arabic bestiary crafted in 1354, probably in Syria. The manuscript is of great importance in the history of Mamluk painting, being one of the few manuscripts of the period that provides both the date of its compilation (755 in the Islamic calendar) and the name of the compiler, Ibn al-Durayhim al-Mawṣilī.

It is possible to place the manuscript in the textual tradition of bestiaries derived from Aristotle’s Zoology and Ibn Bakhtishū’s medical treatises. Only five illustrated manuscripts in the tradition are extant—three in Arabic and two in Persian—one of them dispersed, its miniatures kept in various collections. The Escorial codex features ninety-one miniatures of very high quality.

An Encyclopedic Bestiary

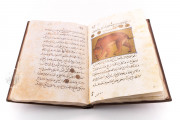

The text groups the living beings in classes: humans, domestic and wild quadrupeds, birds, fishes, and insects. Each animal is introduced by a description of its characteristic features, habits, and reactions in various situations. Then follows an account of the different anatomical parts of the animal and their curative effects on humans.

The two portions of each entry derive from separate textual traditions, the description probably from a translation into Arabic of a pseudo-Aristotelian text on animals by Timoteus of Gaza and the medicinal information from the Book on the Characteristics of Animals and Their Properties and the Usefulness of Their Organs of Ibn Bakhtishū. The author frequently refers to ancient sources, including the Greeks Aristotle, Galen and Dioscorides.

Animals or Emblems?

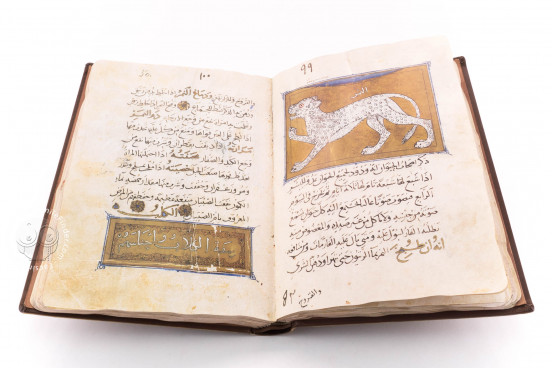

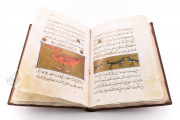

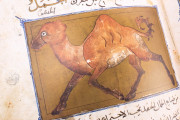

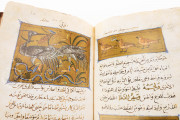

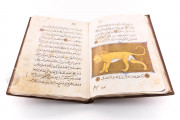

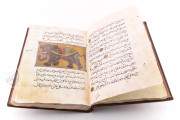

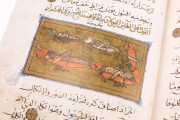

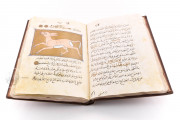

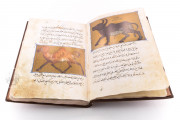

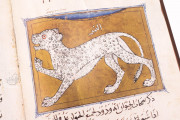

The ninety-one miniatures are an essential complement to the text of the bestiary because the text omits any physical description of each animal. The miniatures do not illustrate any of the particular features of the animals discussed in the text. Nor does the painter attempt to depict the animals in a veristic manner. Instead, the images are essentially emblematic and painted according to established models with great attention to detail.

Many of the animals are shown in pairs, the female and the male, one in motion and the other still. The animals’ eyes are wide open, and their heads are often tilted, with mouths open. Most of the animals are pictured against abstract gold grounds, so the general effect is decorative. Only three miniatures offer a hint of a naturalistic setting: the Herons (fol. 80r), with stylized vegetation and serpentine clouds; the Fish (fol. 118r), with patterned water; and the Crabs (fol. 126r), presenting a strip of grass around the edge of the miniature.

An Unusual Painting Style and Color Palette

The animals were first sketched in black ink, then painted—the paint being thickly textured. Brushstrokes are broad for the body color and fine for the details, a common feature of Mamluk painting. Quite unexpected is the rendering technique used for lights and shadows, painted by juxtaposing gradations of the same color. The palette is also unusual for the absence of the lilac, violet, deep cadmium-red, and bluish-grey common in contemporary Islamicate painting.

The miniatures of the Escorial bestiary are in the customary Syro-Iraqui style derived from the Byzantine tradition with elements of the Baghdad School characteristic of Mamluk painting. Foreign, especially Seljuk and Mongol, influences are especially strong in the Escorial codex and distinguish its paintings from most contemporary Syrian manuscript painting.

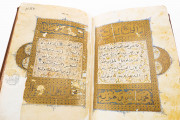

Abundant Use of Gold

The text is written in the elegant, rounded Arabic script called naskh, mostly in black ink. Titles, often in cartouches, are written in white on gold backgrounds decorated with floral motifs and blue stripes. The names of the animals are written in gold with black outlines. Each entry ends with small gold eight-lobed rosettes, each with a red or blue center, a typical Mamluk decorative motif.

More gold rosettes help to articulate the sub-sections of the text. The opening pages of the manuscript are lost, and the text on humans begins in medias res. Glosses are abundant: some supply words missing from the text, others are invocations to Allah.

A Named Scribe

After a final statement, in which the author thanks Allah and claims to have corrected the text by comparing it to the exemplar, the manuscript features two facing colophons (fols. 153v and 154r). Here the compiler, who was probably also the scribe, Ibn al-Durayhim al-Mawṣilī, is named. He was almost certainly not the painter. In all probability, the compilation took place in Damascus, Syria, and the evidence for a Syrian origin is confirmed by the stylistic analysis of the decorations.

Almost certainly born in Mosul, Al-Mawṣilī belonged to a high social class and received a good education, studying Qur’anic sciences and Muslim law. He also studied al-Hāwī, the work of a physician at the Samanid court called Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakarīyā al-Rāzī. Later in his life, Al-Mawṣilī also started a prosperous merchant career travelling to Damascus, Cairo and Aleppo, getting to know several emirs.

Binding

The original binding is lost, perhaps damaged in the great fire of 1671. The current binding is of leather and features the stylized gridiron of Saint Lawrence that is the symbol of the Escorial library.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "The Book of the Usefulness of Animals": Libro de la Utilidad de los Animales facsimile edition, published by Kaydeda Ediciones, 1990

Request Info / Price