The Codex Madrid—also known as the Codex Tro-Cortesianus—originated in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico, perhaps in the Tayasal locale, in the fifteenth century. It is one of the four surviving Maya manuscripts containing almanacs that served as handbooks for divination and prognostication. The others are the Codex Dresden, the Codex Paris, and the Codex Grolier.

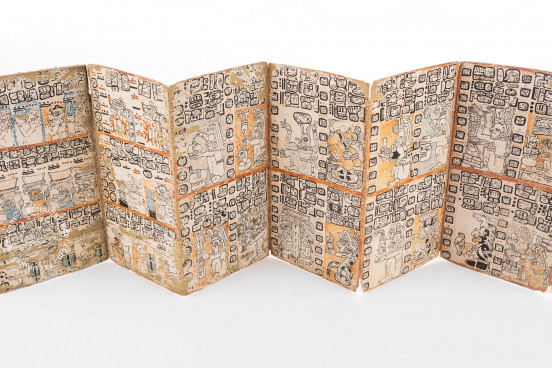

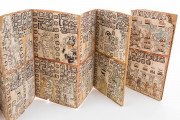

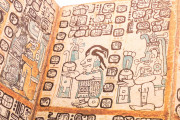

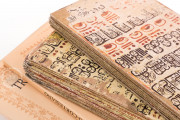

The Codex Madrid is, like the other surviving Maya manuscripts, a screenfold of paper made from the inner bark of a fig tree coated with a thin layer of plaster to receive painting. The manuscript is 22.6 cm high. It is in two parts, the longer being the Manuscrit Troano, which is 416.5 cm long when unfolded. The shorter segment is the Codex Cortesianus, which measures 238.5 cm. Together they form by far the most extensive of the surviving Maya screenfolds with fifty-six panels painted on both sides yielding 112 pages of images, pictographs, and glyphs.

Almanacs concerning the Timing of Ritual and Daily Life

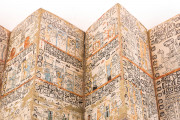

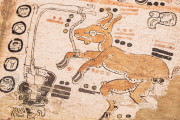

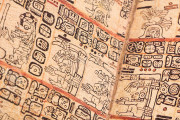

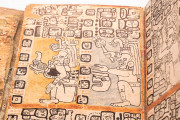

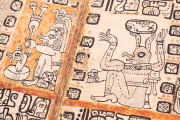

The pictorial and glyphic content of the Codex Madrid is presented in horizontal registers with further grid-like divisions of the surface. Most of the sections marked out include the representation of a deity surrounded by glyphs and pictographs, which together form a sort of thematic almanac addressing aspects of daily life, such as beekeeping, animal trapping and hunting, and planting.

These almanacs are based on the 260-day Maya calendar. Other pages depict ceremonies timed to the 365-day solar calendar. It provides, therefore, glimpses into both public ritual and daily life of the Maya. Its contents were almost certainly compiled from earlier books.

Classic Maya Style

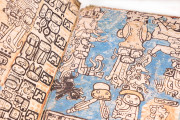

The Codex Madrid was created by nine painter-scribes using brush pens (animal hair mounted on reed handles). Although not the most sophisticated in style of the Maya screenfolds, the Codex Madrid displays the classic Maya color palette of black, brownish-red, and Maya blue, a clear and bright variant of indigo. The red and blue are employed both to color objects and for backgrounds. The blue is sometimes employed in vertical stripes to indicate rain, as on pages 10-11, in connection with the depiction of the rain deity, Chac.

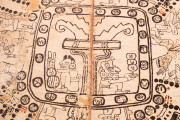

One composition spreads across two panels (pp. 75-76): it shows the Maya creator deities in the center of the universe surrounded by images representing the cardinal points of the compass in a composition reminiscent of a similar diagrammatic representation of time and space in the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer from central Mexico.

A History of Separation and Reunion

It is thought that the Codex Madrid traveled to Europe only after about 1600. A text in Latin and Spanish was written at about that time in New Spain on a piece of European-style paper that was used as a patch to repair damage to the manuscript. It is unknown when its two portions were separated. They were certainly apart in 1866 when the Troano first came to the attention of scholars while in the possession of Juan Tró y Ortolano (1814-1875), after whom it was named.

The Codex Cortesianus was apparently owned by Juan de Palacios in the mid-nineteenth century. José Ignacio Miró sold it to the Museo Arqueológico de Madrid in the 1870s. The two fragments were recognized as constituting a single book by Léon de Rosny (1837-1914) in 1880, naming the combined manuscript the Codex Tro-Cortesianus. The Museo Arqueológico added the Troano to its collection in 1888, reuniting the two portions under one roof, in a collection now known as the Museo de América.

We have 2 facsimiles of the manuscript "Codex Madrid":

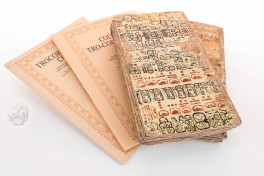

- Códice Trocortesiano facsimile edition published by Testimonio Compañía Editorial, 1991

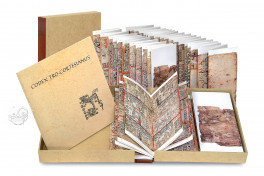

- Codex Tro-Cortesianus (Codex Madrid) facsimile edition published by Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt (ADEVA), 1967