To say the Codex Sinaiticus is one of the most important manuscripts in the world would not be an overstatement. Created in the middle of the fourth century in the eastern Mediterranean, it is among the oldest and most complete books to survive. Additionally, it preserves a nearly complete copy of the Christian bible, a text that fundamentally shaped the history and culture of Western Europe. Named for Mount Sinai, it was kept there at the Monastery of St. Catherine for at least a millennium.

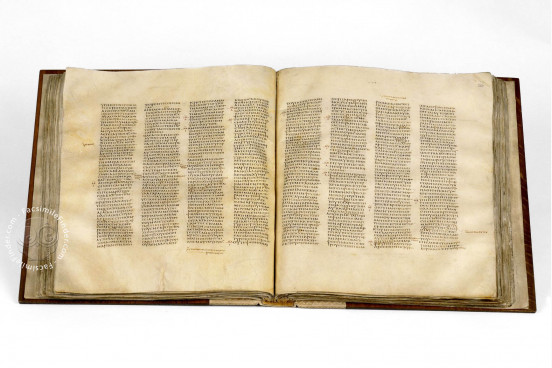

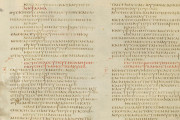

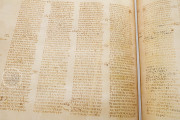

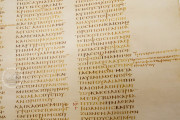

Over four hundred folios comprise the manuscript. The large pages are nearly square. The Greek text is written in Uncial and arranged over four columns of forty-eight lines. No decoration survives, though it is unlikely to have had any. The text has been amended over the centuries. Since the mid-nineteenth century, research has provided valuable insights into the formation of the Christian bible.

The Oldest Complete Copy of the New Testament

Although removed from biblical events by three centuries, the copy of the New Testament preserved in the Codex Sinaiticus is the earliest complete copy of the text that served as the foundation of Christianity.

Along with the Codex Vaticanus, it demonstrates the resources put toward the creation of sacred texts and the importance of pairing Christian texts with older writings to create a singular “bible” that at once contains the history and prefiguration of the Old Testament with the events and letters of the New Testament.

Insight into the Formation of the Bible

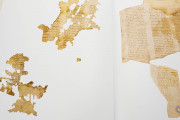

The Codex Sinaiticus contains the Greek text of the Septuagent, however, the manuscript is missing almost all of the first nine quires. The surviving text begins with Leviticus with only fragments from a portion of Genesis.

However, the Old Testament portion does contain additional texts omitted from later versions of the Christian bible: 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, 1 & 4 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Sirach. The New Testament is for the most part complete although the books are arranged in a slightly different order.

Two additional works, the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas, follow the New Testament. Corrections and alterations to the text over eight centuries also serve as important evidence for the fluidity of biblical writings in the early medieval period.

A Manuscript Divided

The full history of the Codex Sinaiticus since its discovery by European researchers is complex and involves multiple nations and legal cases. The text was discovered by Constantin von Tischendorf during a visit to the Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai in the mid-nineteenth century. During a visit in 1845, he was allowed to take 43 folios back to Germany. These are currently the portion of the manuscript housed in Leipzig and were first published as the Codex Friderico-Augustanus.

The remaining 347 folios were taken to Russia in 1859 and kept in St. Petersburg. These were later sold by the Soviet Union to the British Museum in 1933. Additional fragments have since been discovered at Mount Sinai and St. Petersburg.

Binding description

The main block of 347 folios in the British Library was rebound in two volumes divided by the Old and New Testaments in 1935 by Douglas Cockerell within oak boards with white, blind-tooled morocco spines after its acquisition.

We have 2 facsimiles of the manuscript "Codex Sinaiticus":

- Codex Sinaiticus facsimile edition published by British Library, 2010

- Gospel of Matthew from the Codex Sinaiticus facsimile edition published by British Library, 1960