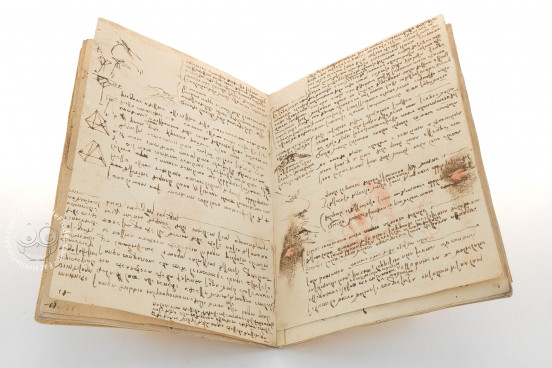

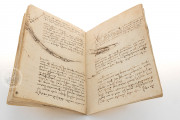

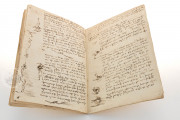

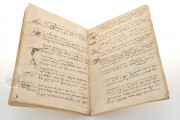

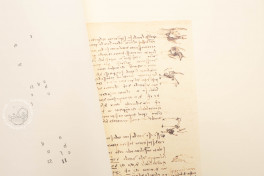

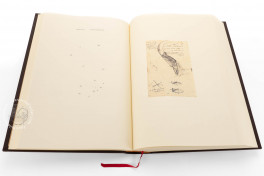

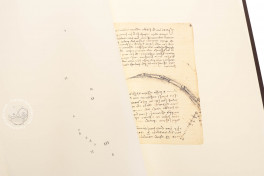

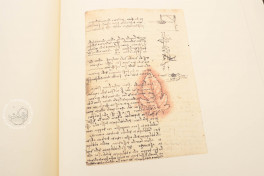

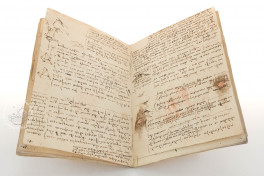

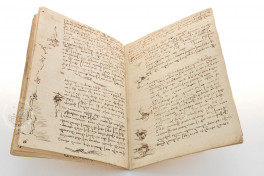

In the Codex on the Flight of Birds, composed between 1505 and 1506, Leonardo da Vinci documented extensive observations and theories that would later become foundational to early twentieth-century aviation. Through meticulous pen-and-ink illustrations, Leonardo explored diverse aeronautical concepts including mechanical principles, metallurgical applications, gravitational effects, wind and water dynamics, feather functionality, wing aerodynamics, and avian movement mechanics.

This remarkable manuscript contains architectural drawings and machine blueprints, but primarily consists of Leonardo's detailed studies on avian flight dynamics. These insights are recorded in Leonardo's characteristic mirror writing, with text flowing from right to left in inverted form.

Leonardo: Renaissance Polymath and Aviation Pioneer

Beyond his renown as a Renaissance artist, Leonardo da Vinci maintained profound interest in technological innovation. He conceptualized various inventions including military designs for armored vehicles and diving apparatus. Among his diverse scientific pursuits, the possibility of human mechanical flight particularly captivated him. Leonardo dedicated over 35,000 words and 500 illustrations to aerodynamics, developing designs for both gliders and helicopter prototypes while systematically investigating atmospheric properties and avian flight patterns.

Historical Influence on Modern Aviation

The Codex on the Flight of Birds has been examined by scholars across centuries. Following its first published edition in 1893, although incomplete, evidence strongly suggests that Otto Lilienthal, the first person to achieve controlled gliding flights, and the Wright Brothers were familiar with Leonardo's aeronautical theories, which influenced their groundbreaking work in aviation.

The Manuscript's Complex Provenance

The Codex underwent a complex journey through the centuries. After Leonardo's death, his student Francesco Melzi inherited the manuscript before it passed to Pompeo Leoni, who organized it with his own numbering system. In 1637, Count Arconati donated it to the Ambrosian Library, from where Napoleon relocated it to the Institut de France in Paris in 1797. The manuscript was subsequently stolen by Guglielmo Libri between 1841-1844, with portions sold in London to Charles Fairfax Murray while the remainder went to Count Giacomo Manzoni of Lugo.

Reconstruction and Contemporary Preservation

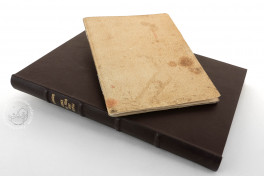

Following Manzoni's death, his descendants sold the majority of the Codex to Teodoro Sabachnikoff, a Russian Renaissance scholar who acquired one of the London folios (folio 18) and published the first printed edition in 1893. Sabachnikoff donated the manuscript to Queen Margherita of Italy, who entrusted it to the Royal Library of Turin. The Codex was gradually reconstructed through subsequent acquisitions: folio 17 in 1913, and the remaining folios (1, 2, and 10) purchased by Enrico Fatio and later donated to King Victor Emmanuel II. Finally bound in 1967, the complete Codex remained unlisted in storage until being catalogued in February 1970 as Varia 95.

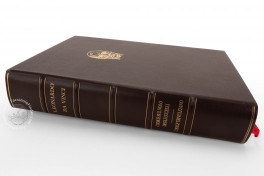

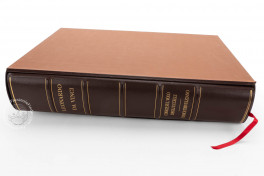

We have 5 facsimiles of the manuscript "Codex on the Flight of Birds":

- Codice sul Volo degli Uccelli e Codice Trivulziano facsimile edition published by Art Market, 1989

- Codice sul Volo degli Uccelli (English and French Edition) facsimile edition published by Giunti Editore, 1976

- Codice sul Volo degli Uccelli (Italian Edition) facsimile edition published by Giunti Editore, 1976

- Códice sobre el Vuelo de los Pájaros facsimile edition published by Patrimonio Ediciones, 2019

- Codice del Volo degli Uccelli facsimile edition published by Collezione Apocrifa Da Vinci, 2013