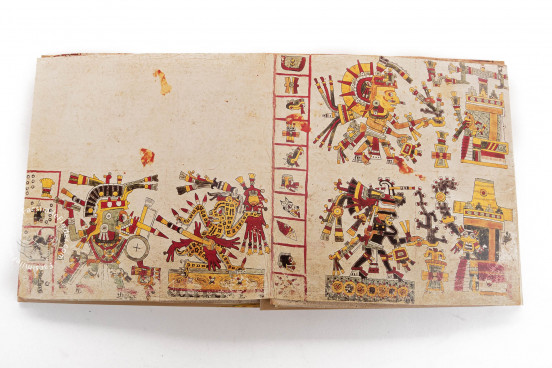

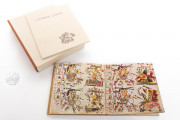

Despite its nickname, the Codex Cospi is not a manuscript of folded sheets sewn at the spine. It is a screenfold manuscript from the Puebla-Tlaxcala region of Mexico probably dating from the early sixteenth century. It is an almanac for religious leaders in divination and ritual events. Pictographs, or read images, of deities, day symbols, ceremonials, and deity impersonators in the Mesoamerican tradition comprise the content of this guide written for indigenous ritual practitioners.

It is one of the Borgia Group of manuscripts, named for the Codex Borgia and which includes the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, the Codex Laud, and the Codex Vaticanus B. The panels of the Codex Cospi are nearly square.

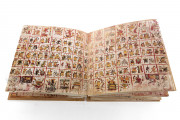

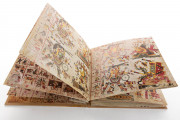

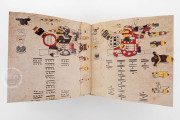

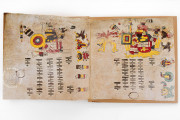

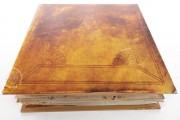

When unfolded, the screenfold's length extends to 364 cm. Five rectangular polished leather strips of varying lengths were glued together to create the support, which is covered with a thin layer of plaster. Twenty-four of the manuscript's forty pages have received painting, thirteen on the obverse and eleven on the reverse. The images on the obverse present the tonalpohualli, the 260-day cycle Aztec calendar. The painted pages on the reverse contain rituals involving bundled offerings.

Two Artists' Tools of the Trade Identified

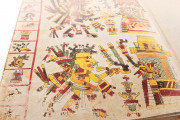

Two painter-scribes created the manuscript, one responsible for the obverse and the other for the reverse. The painter-scribe of the obverse used continuous, smooth black outlines to create forms filled with opaque colors. His tool was a brush firmly grasped by a tight fist, held in a vertical position. Before supplying the figural art, the painter-scribe divided the page using thin red lines to create boxes for days of the calendar. The painter-scribe of the reverse divided each panel into two horizontal registers using a fine graphite line. The black outlines were created using a pen rather than a brush, which has led scholars to speculate that this artist was working after the arrival of the Spaniards, who brought with them the habit of using a quill pen.

Content in Four Parts

The obverse is comprised of three sections. Panels 1-8 form a complete almanac of the 260-day calendar. Arranged in five tiers of fifty-two days, they are read from the lower left of panel one to the upper right of panel eight. Panels 9-11 show the Venus deity piercing five figures, each representing a dangerous four-day period. These three pages are to be read in a boustrophedon (zig-zag) pattern bottom to top, top to bottom, bottom to top. On the next two panels,12-13, the days are arranged in four groups (associated with a crocodile, a jaguar, a deer, and a flower) representing the cardinal points of the compass and the seasons. The images portray deities and deity impersonators placing offerings in front of temples.

The reverse of the screenfold illustrates rituals, one per panel, that revolve around the presentation of offerings of counted bundles to certain deities. Bestowing these bundles was a method of ensuring safety and good luck.

From Mexico to Bologna

It is possible, but not certain, that the Codex Cospi was among a group of Mexican objects given by the Spanish Dominican Domingo de Betanzos (1480-1549) to Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici) in 1532/1533, when Clement visited Bologna and that—for reasons unknown—it remained in the city rather than traveling to Rome. The manuscript was given in 1665 by Valerio Zani to Marquis Ferdinando Cospi (1606-1686), a collector of curiosities. In 1672, Cospi donated his collection to the city of Bologna, and it was housed in the Palazzo Pubblico. The "Museo Cospi" was transferred in 1742 to the city's Istituto delle Scienze. The institute became part of the University of Bologna in 1803, and the object is now housed in the Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna.

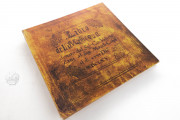

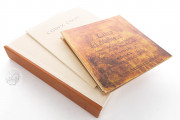

Seventeenth-Century Binding

The parchment covers of the screenfold were almost certainly created on the occasion of the presentation of the manuscript to Cospi. Both front and back covers are decorated with fan motifs, and an inscription on the front cover proclaims in Italian that the manuscript was given to Cospi by Zani on December 26, 1665. That inscription also reveals that the object was believed at the time to be from China, a misapprehension that was later corrected.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Codex Cospi": Codex Cospi facsimile edition, published by Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt (ADEVA), 1968

Request Info / Price