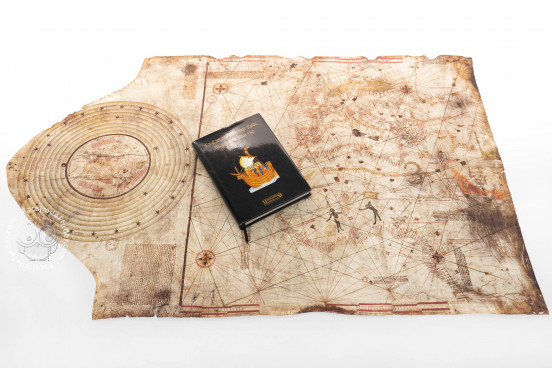

This unsigned chart, probably made in the late fifteenth century, is an interesting example of late medieval cartography. Although it has been known as the "Columbus Chart", its attribution to Christopher Columbus has not been generally accepted. The chart represents the Mediterranean area, mid-northern Africa, Europe, and the Near East, as well as several islands of the Atlantic Ocean. It also contains a circular world map at the left-hand edge of the map, surrounded by circles portraying the celestial spheres.

Containing both graphic and textual information, this chart represents the geographical knowledge available at the time. Nevertheless, the coexistence of two different views of the world on the same map, i.e. a typically fifteenth-century nautical chart and a more traditional world map, makes this chart a transitional map between the late medieval tradition and early modern charts.

Between Tradition and Modernity

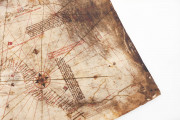

This chart is made on parchment, and measures 112 x 70 cm. Oriented to the north, it portrays most of the known world at the time following the tradition of nautical charts. The northern limit of the chart is southern Scandinavia, while the southern edge is the mouth of the Congo River, presented here with the Portuguese name of Poderoso Fl. ("Powerful River").

Although the chart is undated, several features allows us to suggest a rough dating. The world map beside the chart represents the whole African continent, which was circumnavigated by Bartolomeu Dias in 1488. In addition, in the chart we can see the flag of Castile over Granada, which was taken from the Arabs in 1492. Thus, the chart had to be created after that date.

The abundant place names on the coasts of the continents are written mainly in Portuguese. This detail has been used by some scholars to suggest that the chart may have a Portuguese origin.

In Africa, two black-skinned men are portrayed, one of them with a bow and an arrow, and the other holding a shield. Abundant cities are also drawn, both in Africa and in Europe. We can also see many flags and banners all over the chart, as well as four symmetrically located compass roses.

Following the traditional representation, the Red Sea is colored in red, while the Baltic Sea is in green. The chart contains also several explanatory texts and inscriptions, stemming from different sources.

The circular world map depicted in the left-hand edge of the chart is more traditional, although it portrays a larger Africa, reminding us of the Portuguese voyages around the southern edge of the continent. This circular world map is also accompanied by texts, written in Latin, from Pierre d'Ailly's Imago Mundi, one of the most influential geographical works of the fifteenth century.

This world map, surrounded by the nine circles of the planets and stars, shows a clearly Christian view of the world. It is centered on Jerusalem and represents the Terrestrial Paradise as an island in the far east, surrounded by mountains.

Interestingly, on the eastern coast of Asia, we can see several islands visited by St. Brendan, who, according to tradition, sailed the Atlantic Ocean for seven years before reaching the Paradise in the west.

Several details of both the chart and the world map contained in it, such as the sources used by the author, the importance of the city of Genoa and the emphasis on commercial information, allowed some researchers, like the French historian Jacques de la Roncière, to suggest that the author of the chart was Christopher Columbus. Nevertheless, this attribution has not been generally accepted.

Be that as it may, this chart, held in the National Library of France under the shelfmark GE AA-562 (RES), is a very interesting example of the transitional maps of fifteenth-century southern Europe.

A Chart With an Unknown History

Little is known about the provenance of this chart. It was acquired by the National Library of France in 1848, but its previous owners are unknown. It was studied and presented by the French scholar Jacques de la Roncière in 1925.

Much later, the scholar Danielle Lecoq, after checking Columbus’ personal copy of Pierre d’Ailly’s Imago Mundi held in the Columbian Library in Seville, pointed out that, in one of the abundant marginal notes of that copy, Columbus mentions four charts of paper, all of which contain a sphere. This might suggest that Columbus owned this chart, although he was not its creator. Nevertheless, this is just a theory – the real history of the map remains unknown.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Christopher Columbus's Chart, Mappa Mundi": La Carta de Cristóbal Colón, Mapamundi facsimile edition, published by M. Moleiro Editor, 1995

Request Info / Price