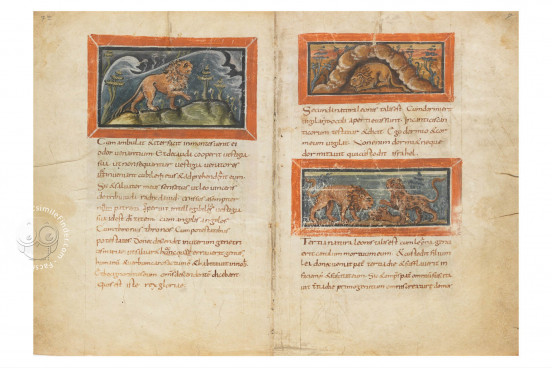

The medieval bestiary collects descriptions of animals—both real and imaginary—birds, and rocks and accompanies these with moralizing explanations. The bestiary of the Middle Ages was a compilation of a variety of sources, the primary one being the Physiologus. The anonymous author of this Greek text, likely working in Alexandria in the fourth century CE, drew source material from several ancient authors from all parts of the world known to Europeans. Some of the earliest witnesses of the Physiologus are in Latin translation. One of the oldest of these is the Bern Physiologus, renowned for being the earliest exemplar with painted illustrations.

The Physiologus is but one small portion of a larger compilation of Latin texts in the Bern manuscript. An extended life of Saint Simeon Stylites and eighteen short summaries of the lives of Christian fathers join the Physiologus. Apart from the large, decorated initial opening the life of Saint Simeon, the only illustrations in the book are the thirty-five miniatures in lively colors interspersed through the Physiologus. Most of the book is dedicated to the Chronicle of Fredegar. A short reading from the Gospel of Matthew followed by a related commentary by Saint Ephrem ends the original codex, and two short texts were added later.

Iconic Images of the Animal World

An ornamental initial S featuring light washes of color within the body of the letter and some interlace decoration opens the life of Saint Simeon. The short chapters of the Physiologus containing the allegorizing descriptions of beasts are introduced by miniatures illustrating their content. Most are set in thick red frames, while others are unframed and set directly onto the blank parchment. The variable arrangement of text and image indicates a close coordination between the scribe and illustrator. Some instances of planning are demonstrated in the traces of visible underdrawings.

The images of the Bern Physiologus are significant for constituting the oldest extant pictorial cycle of the text. The iconography of the miniatures endured for centuries in a variety of artistic media as the rich symbolism of these moralizing descriptions was used in a multitude of applications that went far beyond the boundaries of what would become the medieval bestiary manuscript tradition.

The Scribe Haecpertus

The colophon at the end of the Saint Ephrem commentary (fol. 130r) reveals that the book was written by a scribe named Haecpertus—a variant of the name Egbert—and asks the reader to pray for him. Haecpertus was likely the sole scribe involved in the production of the original textual compilation.

The careful Caroline Minuscule Haecperpus writes (along with the strange variant of his name) is not typically found in manuscripts made in the region surrounding Reims, where the manuscript is generally assumed to have been made. Display capitals in red and brown announce different chapters and are written in fine Uncials, and Rustic Capitals are also used (such as in Haecpertus' colophon).

A Book for Humanists

Nothing is known about the original patron of the Bern Physiologus, and few inscriptions help experts reconstruct its provenance. The codex ends with an early fifteenth-century inscription indicating that the book had belonged to a member of the respected family Bachelier in Reims. The humanists Pierre Daniel and Jacques Bongars, presumed to have been owners of the manuscript, are identified in inscriptions (fol. 1r). The Bern Physiologus was donated to the Bern library in 1632 by Jakob Graviseth.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Bern Physiologus": Physiologus Bernensis : voll-Faksimile-Ausg. des Codex Bongarsianus 318 der Burgerbibliothek Bern facsimile edition, published by Alkuin Verlag, 1964

Request Info / Price