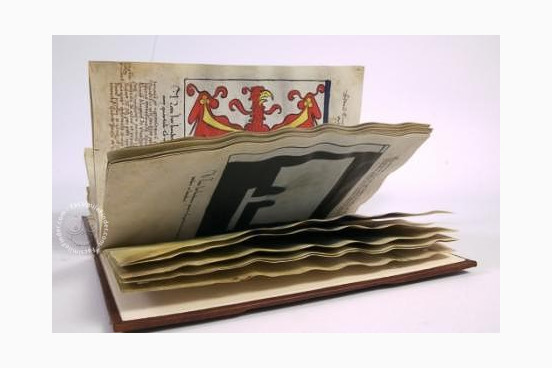

Jan Dlugosz's Banderia Prutenorum is a unique and unrepeatable work of the banners of the Teutonic Knights gained mainly in the Battle of Grunwlad. This manuscript was made in the case of destruction or loss of banners so Polish nation has not forgotten about what was won in the biggest battle of the Middle Ages.

The largest battle of the Middle Ages

In Anno Domini 1410, on the day of the feast of the Dispersion of the Apostles (i.e. 15 July), the combined armies of the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania crushed the forces of the Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem. This battle, commonly known as the Battle of Grunwald (also the First Battle of Tannenberg), was not only a great victory for the Polish army, but also the largest battle of the Middle Ages. To this day historians argue about the size of the opposing armies. One thing is certain though – the battle involved tens of thousands of knights – among them the famous Zawisza of Garbów, also known as the Black Knight. The Polish King, Wladyslaw II Jagiello, failed to capitalize on the overwhelming victory immediately but, nevertheless, managed to break the military might of the Teutonic Order which would never again pose such a threat as on 15 July 1410. Many brothers perished on the battlefield that day, including the Grand Master of the Order, Ulrich von Jungingen. Countless others were taken into captivity, including knights serving the Order and its guests. From around 250 brothers, some 200 were killed.

Precious Banners

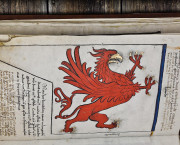

Among numerous spoils, the Polish army also took Teutonic banners. In those times, knights fought grouped in regiments, and banners flapping in the wind showed the direction of the unit or the rally point in it became dispersed. To bear the banner in battle was a great honour, to steal it from the enemy was an important success, but usually most banners were captured after they were thrown away during flight. Banners were often decisive to the fates of battles – their fall, seen as a herald of inevitable defeat, could break the morale of soldiers. During the battle of Grunwald, the Teutonic army nearly captured the great banner of the Cracow District with the coat of arms of the Crown; their attempt was foiled by the Polish knights.

Every group of soldiers going to battle was led by a banner featuring the coat of arms or emblem of the town, bishopric or noble house providing the unit. There were also special elite banners under which served the most distinguished knights, for example the Black Knight went into battle under the abovementioned great banner of the Cracow District.

In the battle of Grunwald Polish knights captured over 51 banners of Teutonic knights, their Prussian vassals, guests and allies. Some of these banners, as war trophies, were deposited in the Cathedral of Vilnius where they probably burned in a fire in 1530. The remaining 51 were placed as votive-offerings in the Chapel of St. Stanislaus, the patron saint of Poland, in the Cracow cathedral. These were joined by other banners captured from the Teutonic knights – one taken at Krone on 10 October 1410 and four at Nakel on 13 September 1431. There they hung for 38 year but the memory of their owners slowly faded.

The memory of the most important ones, the banner of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, the Dukes of Oels or Pomerania, persisted, but others were often confused. Only in 1447 was it possible to refresh the information on the banners as on 24 June, in relation to the coronation of Casimir IV Jagiellon, Cracow was visited by a Teutonic mission lead by the Grand Hospitaller Heinrich von Plauen. Envoys also arrived the next year as the young king demanded that the Peace of Brzesc Kujawski of 1435 be resworn. Presumably during one of these visits Jan Dlugosz, the future mentor of the sons of Casimir IV Jagiellon, inquired the Teutonic diplomats about these banners. The memory of the defeat and of those who fell in battle was still strong among the brothers, and those who still remembered these images from their youth could still recognize the coats of arms during their painful visit in the Cracow cathedral. With the help of the envoys Dlugosz described the banners and ordered that their colourful images be made. This was their first historical documentation because, as commented by the initiator and author of the project, when the images fade in time, it will be possible to make copies.

One of a kind manuscript

Such are the origins of the Banderia Prutenorum, i.e. Blazons of the Prussians. The manuscript was created in three stages. The first involved creating images of the banners and providing comments indicating their dimensions and signatures. In the second, brief descriptions, probably by the hand of Dlugosz himself, were created, while the third consisted in adding supplements and titling the work. The first stage, tracing the banners and measuring them, took place on 29 March 1448. The painter, Stanislaw Durink, initially intended to place one image on every leaf. However, he concluded that he would not be able to fit all of them (the parchment prepared for the manuscript initially had 5 sheet, 10 leaves each, i.e. 50 pages) and started placing banners on both sides of leaves.

From page 9 to page 32 Durink painted banners on both sides of leaves (page 27 was empty), but reverted to the initial system from page 33. Banners were always painted with a vertical flagstaff – depicted as they were displayed in the chapel, i.e. with flagstaves vertically attached to pillars to make them fully visible. The images exhibit utmost care to faithfully reproduce the originals. It was probably painter Durink who added comments indicating the dimensions of banners in ells (darker ink) and the terms longitudo (length) and latitudo (width) by the images. The same hand at the end of the manuscript, under the drawing of a bald man wrote: Expliciunt banderia Prutenorum per manus picta Stanislai Durink de Cracovia die Veneris 29 Martii 1448, i.e. End of Blazons of the Prussians painted by the hand of Stanislaw Durink from Cracow on Friday 29 March 1448.

After the images were finished, another hand, most likely Jan Dlugosz’s, added short comments about the banners. These contain information about the owner and leader of the given regiment. The only banners described in more detail are the banner of St. John, under which served the guests of the Teutonic Order and the first banner of the Culm District. In thirty four cases the leader of the banner is indicated, in sixteen he is unknown; in the remaining six the owner of the banner was uncertain (only brief descriptions were provided, e.g. “German knights”, “mercenaries from Rhineland” etc.). The informer of the chronicler had better knowledge of the commanders and vogts of the Teutonic Order than of the leaders of bishopric and municipal banners; accordingly, he was most likely a Teutonic monk.

These comments were supplemented with others written in a lighter ink by another hand. These were created throughout many years after 1457 based on information received from the Teutonic knights. Their author remains unknown – it could have been Dlugosz himself (or maybe he only dictated them or provided notes to be copied and reviewed) or one of the brothers of the chronicler.

Later the codex was bound (though the initial binding did not survive until today). As the parchment leaves bear signs of rust, the 15th century binding must have had iron corner pieces. Currently the manuscript is bound in stamped dark brown leather from the 16th century which was carefully renovated in the 20th century. Banderia Prutenorum as whole survived in a very good condition. It is composed of parchment sheets folded in five (so-called quinternions) of which each contains 10 leaves, two pages each. The last fifth section has 7 leaves (i.e. 14 pages). One leaf was cut out and along with it the image of the face side of the banner of the Grand Master of the Livonian Order. Accordingly, initially the last section had 16 pages with one sheet being used as the cover. This gives a total of 5 sections 10 leaves each, i.e. 50 pages of which 47 survive today.

The existence of such a cover is further supported by the fact that the first and last leaves bear no marks of staining. The number of each section is written at the bottom of the first page. Primus, Secundus etc. These words were partially cut by the bookbinder in the process of binding. Leaves also have three numberings written in pencil, but these were added much later – the last is from the 19th century. However, they are not consistent and have deficiencies.

The parchment of the Banderia comes from northern Europe and is smoothed from both sides (to allow writing on both). With the next, 16th century binding, additional unnumbered paper leaves were added – these have a different colour and are less damaged. The first parchment page features the inscription (probably made by Dlugosz) Pro libraria universitatis studii Cracoviensis datum per dominum Johannem Dlugosh, i.e. For the library of the University of Cracow, a gift from master Jan Dlugosz. It also features numerous other additions, mainly from the 16th century, written by the professors and librarians of the Jagiellonian University. Apparently, Jan Dlugosz donated his manuscript to the university. As attested by the quoted dedication, he did it during his lifetime.

In the 16th century, in an unexplained turn of events Banderia Prutenorum found its way to the Library of the Cracow Chapter whose stamp is visible below. This is also when the codex we re-bound. Consequently, the phrase universitatis studii Cracoviensis was crossed out in the dedication and overwritten with Ecclesiae cathedralis Cracoviensem. The manuscript remained there until May 1940 when it was seized by the authorities of the German General Government. It was gifted by Hans Frank (the Nazi governor of occupied Poland) to the authorities of Malbork. Later, after the war, the manuscript in baffling circumstances was found in an antique bookstore in London and was subsequently purchased by the Polish embassy and sent back to Poland. Currently, as per the author’s wish, it resides in the Library of the Jagiellonian University.

The fates of the banners

The fates of the banners, however, remain unknown. We know for certain that they were displayed in the Chapter of St. Stanislaus as late as the 16th century – they were seen by Bartosz Paprocki who described them along with flagstaves in his Coats of Arms based on the manuscript of Jan Dlugosz. They were also seen in 1597 covered with a thick layer of dust rendering them nearly beyond recognition, but according to the Guide to Cracow Churches they remained there until 1603. Their later fate remains unknown, most likely they did not survive the Swedish Deluge. There is a memo according to which in 1797 the Teutonic banners were transported to the Military Museum in Vienna (the past and present seat of the Teutonic Order), but which banners they were and what later happened to them is unknown. In 1900 copies of 50 banners were made, throughout 1937-1939 these were supplemented with further reconstructions. These were later given by the authorities of the General Government along with Dlugosz’s manuscript to Malbork. Some of these copies survived the war and in 1962 copies of seven more standards were made. The remaining 36 banners were reconstructed recently in the Fabric Conservation Workshop of the Wawel Royal Castle. Restoration works were completed in October 2009. This was made possible by the Banderia Prutenorum, exactly in accordance with the wishes of the author, who had hoped that the descriptions provided in the codex would be used to reconstruct the valuable banners which would begin to crumble along with the passage of time.

The significance of this manuscript is hard to overstate. It is a unique catalogue describing medieval banners. Thanks to it, we can not only discover the emblems of towns and commandries (administrative unit of military orders), but also the Teutonic military organization and the manner of mobilizing these troops. Owing to this manuscript we also know that the first regiment provided by a commandry was led by the commander, the second by the vice-commander. If needed, commandries also provided a third regiment. Hence the two banners from Culm with a very similar coat of arms, three from Danzing and Elbing. There were only slight differences between the banners, mainly regarding the colours or other details.

Binding description

16th century binding, stamped dark brown leather and renovated in the 20th century.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Banderia Prutenorum": Banderia Prutenorum facsimile edition, published by Orbis Pictus, 2009

Request Info / Price