Selected excerpts from the commentary by Kristine Edmondson Haney on the Winchester Psalter and its famous miniature cycle, a true masterpiece of English Romanesque illumination.

The Winchester Psalter is justly famous for its prefatory miniature cycle, expanding across thirty-eight leaves as it sweeps through biblical history. the codex consists of an extensive cycle of 38 full-page illuminations depicting events described in the Old Testament, scenes of the life of Christ, the Last Judgement and the Second Coming

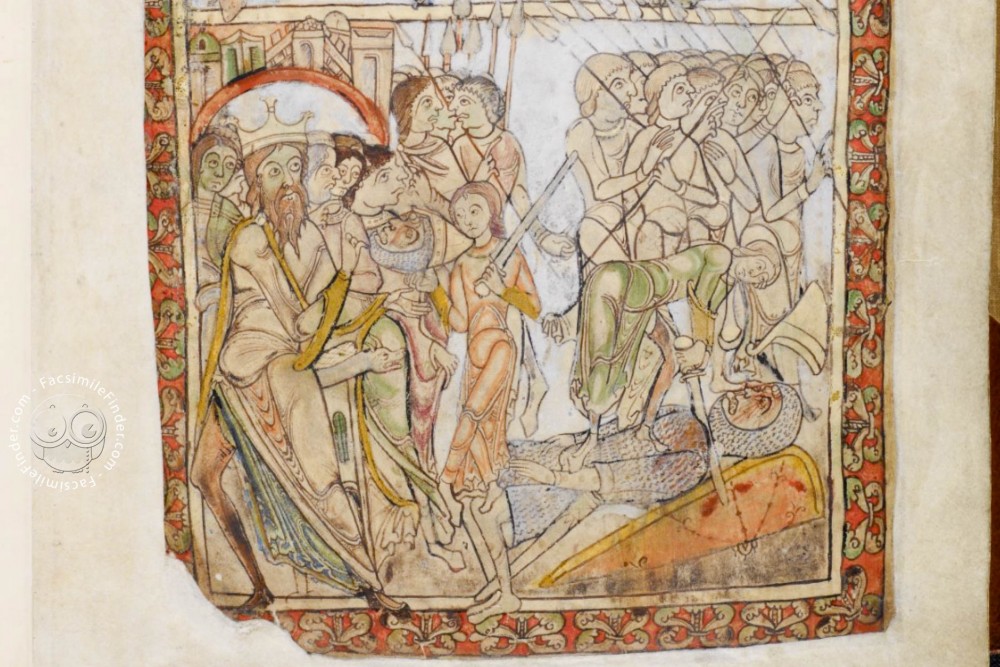

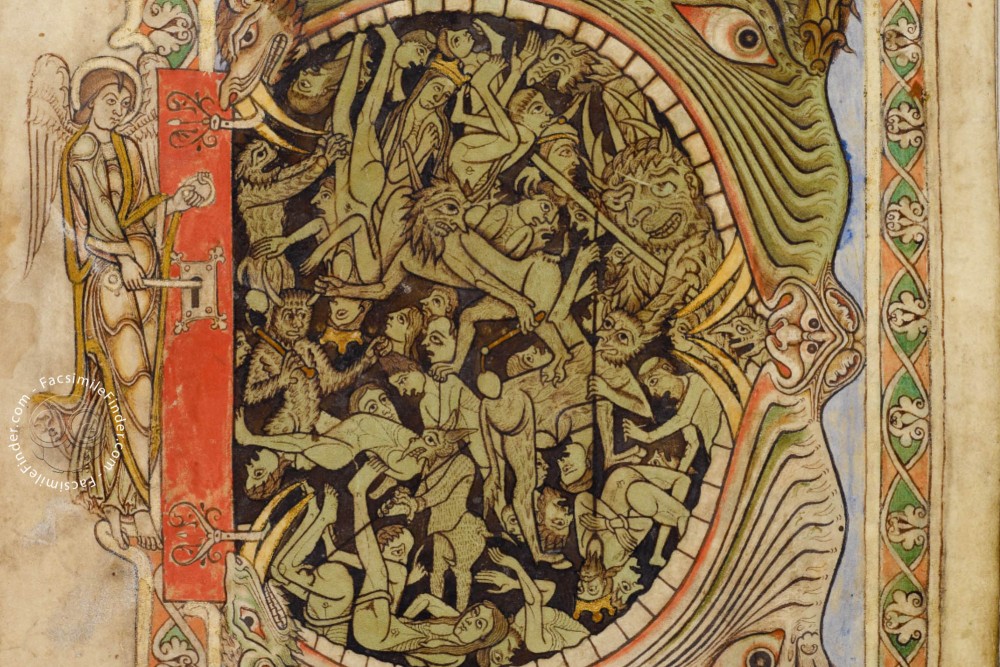

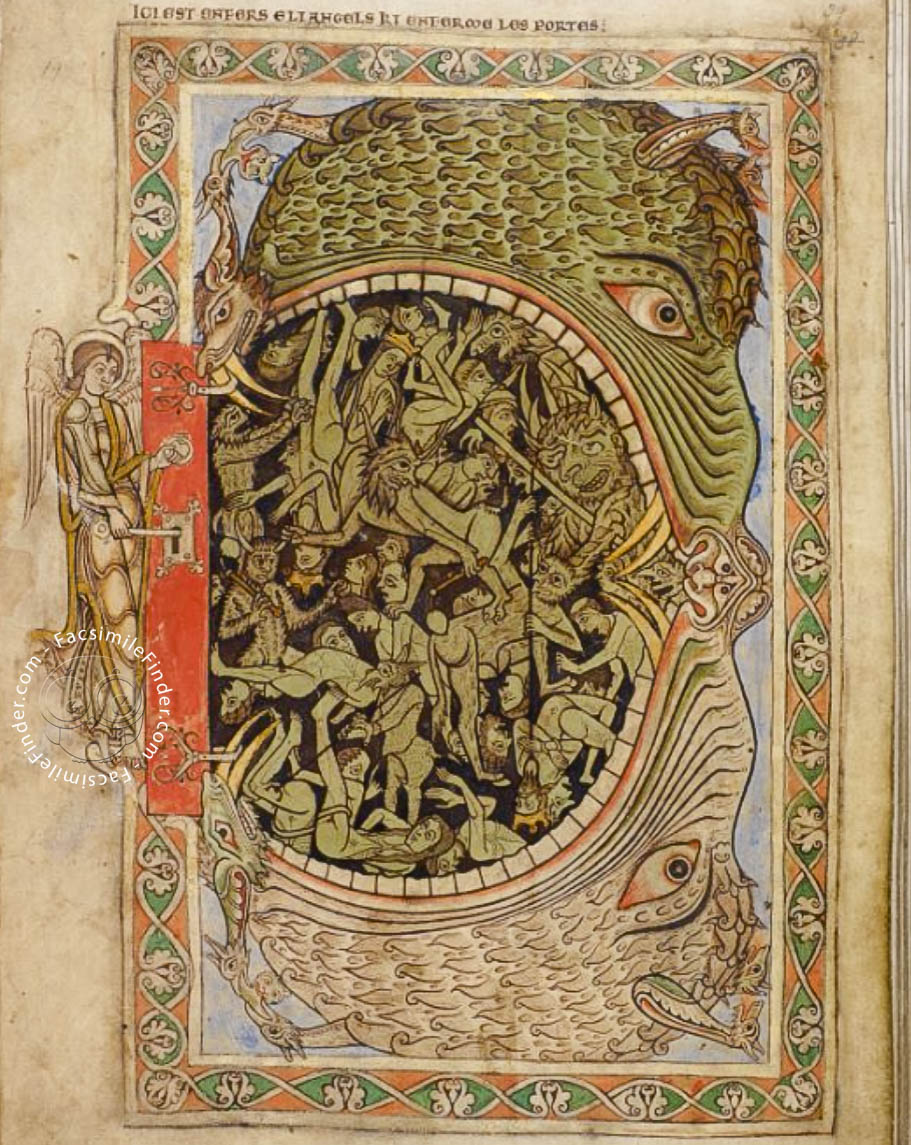

The deftly executed pen drawings accented with tinted wash illustrate scenes from the Old Testament, the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary, and the Last Judgement. These paintings are ingenious and original in their overall design and execution, with powerfully characterized biblical figures stepping forth to tell their story, and make this manuscript remarkable in a century that produced a number of the most beautiful and memorable works in the history of English art.

The Psalter in the Middle Ages

On the most elementary level, the Winchester Psalter illustrations provide a cogent introduction to the stories of the Bible. However, to best understand this miniature cycle we need to look first at the principal text to which they are attached, the Old Testament book of Psalms, believed in the Middle Ages to be the work of David, second king of Israel. It is a collection of religious poetry in which one or more individuals address God and express faith in God or longing for nearness to God. […]

The Psalms played a large part in the Jewish liturgy and later an extremely important public and private role in the life of Christians in the Middle Ages in the areas of prayer and study. From at least the fourth century Christians included the Psalms in daily prayer meetings. Psalms were also incorporated into the Mass, and this remains part of traditional usage. […]

Considering the importance of the Psalms in medieval life, it is not surprising that they were copied out and produced separately from the rest of the Bible in a book termed a Psalter. The earliest extant Psalter dates from the sixth century and thousands were produced in the Middle Ages.

Some were produced for public use in the Mass and Divine Office and others for private prayer and study, but only a small percentage of them were embellished with pictorial decoration: illustration was not an especially easy task for a non-narrative poetic text. One approach was to illustrate the words literally, but more often the illustrations were an amplification or commentary on the text. Portraits of David, often with his musicians, or scenes from his life were most common in early Psalters.

David was an obvious choice, not only as supposed author of the Psalms but also as one of the principal Old Testament types of Christ. This explains the heavy concentration of scenes from the life of David in the Winchester Psalter, as a shepherd, rescuing the ram, anointed by Samuel and in his contest with Goliath. […]

Characters as role models for appropriate and inappropriate behaviour

The Winchester cycle has a clear devotional bent, but this does not exhaust what it offers to the viewer. The selection of scenes and their execution not only assists in petitions for forgiveness but offers examples on how to lead a life worthy of forgiveness, and its opposite. In other words, the characters and subjects also become role models for appropriate and inappropriate behaviour.

Those worthy of emulation include the gentle Abel, righteous Noah, faithful and obedient Abraham and Isaac, morally upright Joseph, capable leader Moses, courageous David, joined by the exemplary actions of Christ, the Mother of God, and the apostles. Against these are the disobedient Adam, Eve, and the population drowned in the Flood, the jealous, murderous Cain and Herod, the deceitful Devil and avaricious Judas, among others.

Lessons for living

Not only the subjects but the powerful characterisations of many biblical figures assist the viewer in separating out right from wrong. The submissive Abel receives a crushing blow from the snarling Cain. A fragile David overpowers the menacing, muscular lion and towering Goliath.

Tiny, innocent children are ripped to pieces by monstrous soldiers at Herod’s command. A heroic Christ leaps away from the Devil who is cunningly garbed as a woman, and elsewhere is tortured by subhuman figures replete with animalistic features and fangs. The rewards and punishments for these two patterns of behaviour are also clearly juxtaposed.

For example, Noah is saved while the dissolute perish in the Flood. This dichotomy extends into the Last Judgement cycle, where the Saved move serenely into Paradise while the Damned are tortured by savage demons and suffer eternal torment locked in the most memorable extant Hellmouth. In sum, on this level the cycle offers the viewer lessons for living. While these were normally learnt in childhood, they remained essential throughout life, especially for those in positions of power and authority. […]

Highest quality work

The subtlety and variety displayed in the drapery patterning are equalled by the artist’s shading technique. Most often colour follows the outlines of the drawings, giving the effect of a shadow, softening the otherwise harsh pen line. In places colour also indicates musculature or the texture of hair, beards, chain-mail and fur. The overall impression is one of a superb draughtsman capable of the highest quality work, which displays meticulous attention even to the slightest detail. […]

The original provenance of the Winchester Psalter

While this manuscript has long been termed the Winchester Psalter, it is worth exploring whether this is appropriate. Many artistic features do point to Winchester, which was the capital of England before the Norman Conquest, having two Benedictine monasteries and a convent of nuns.

Both of the Anglo-Saxon monastic foundations produced illuminated manuscripts, but after the Norman Conquest activity at these scriptoria apparently ceased, since no illuminated manuscripts from Winchester survive from the late eleventh or early twelfth centuries. However, the situation changed around the middle of the twelfth century, when the Winchester Psalter was produced. This date is based on various considerations, including the absence from the calendar of the feast of Edward the Confessor, who was canonised in 1161.

A number of scenes in this cycle are tied to Anglo-Saxon manuscripts produced or amended in Winchester, including two tenth-century manuscripts, the Aethelstan Psalter (London, British Library Cotton Galba A.XVIII) and the Benedictional of St Aethelwold (London, British Library Add. 49598), the Tiberius Psalter and the eleventh-century New Minster Register (London, British Library Stowe 944).

There are also connections to new developments in Winchester at around the mid-twelfth century, including a Psalter (Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional Vit. 23–8) and two splendid Bibles. Both the Bible that remains in Winchester Cathedral Library and the other (Oxford, Bodleian Library Auct E. inf. 1–2) are similar to the Winchester Psalter in some design and stylistic features. There are also connections to a pair of c.1150 enamel plaques now in the British Museum, one depicting the bishop of Winchester, Henry of Blois. […]

Henry of Blois, great collector and lover of art

But who at Winchester suits the wording of this prayer to St Swithun and the nature of this manuscript more generally? Over the course of nearly a century the Winchester Psalter has often been associated with Henry of Blois, a grandson of William the Conqueror who entered monastic life at the Benedictine monastery Cluny in France.

He was called to England in 1126 by his uncle King Henry I to become abbot of Glastonbury, the wealthiest Benedictine house in England. He continued to hold this post when Henry I appointed him bishop of Winchester in 1129. Henry of Blois would remain active in affairs of Church and State until his death in 1171. He was known to be an art lover, on one occasion buying ancient statuary in Rome.

In addition to outfitting his private palaces with art works he also generously endowed both Glastonbury and Winchester with luxurious liturgical objects and books. […]

However, there is no certainty the Winchester Psalter was written for Henry; another male ecclesiastic in Winchester is also a plausible possibility. […]

The production of the Winchester Psalter

Taken together, this evidence suggests the Winchester Psalter was produced before 1161, probably for a male ecclesiastic associated with St Swithun’s Priory and possibly also intended by that individual for the spiritual direction of others. As such, the Winchester Psalter would take its place in a long continuum of private Psalters produced for male ecclesiastics, stretching back before the Norman Conquest to include the Tiberius Psalter and well into the thirteenth century when a luxurious Psalter (London, Society of Antiquaries 59) was fashioned for Robert de Lindesey, abbot of Peterborough. […]

Additions to the calendar indicate that at some time in the thirteenth century the Winchester Psalter passed into the hands of the Benedictine nunnery dedicated to the Virgin Mary and St Edward at Shaftesbury. It was here that the red Anglo-Norman French captions were added to the picture cycle. This shows that nearly a century after they were fashioned the miniatures were still a source of interest and study. The charming simplicity of these captions suggests that they were intended to provide a very basic introduction, of the sort we can imagine especially appropriate for young learners. At some time before 1638 the Winchester Psalter became part of the collection formed by Sir Robert Cotton, beginning around 1588 and enlarged by his son Thomas and grandson John before it was presented to the nation in 1702. The Cotton family heritage continues, as the Winchester Psalter is now London, British Library Cotton Nero C.IV. […]

About Kristine Edmondson Haney, the author

Professor Emeritus of Art History at UMASS and author of The Winchester Psalter: An Iconographic Study. A member of Phi Beta Kappa, she has also received both the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship and the National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship.

Text published by courtesy of The Folio Society.

Images courtesy of the British Library

Further reading

- Francis Wormald, The Winchester Psalter, London, Harvey Miller, 1973;

- C. M. Kauffmann, Romanesque Manuscripts 1066–1190 (A Survey of Manuscripts in the British Isles, III), London, Harvey Miller, 1975, pp. 105–6, no. 78;

- Kristine Edmondson Haney, The Winchester Psalter: An Iconographic Study, Leicester, Leicester University Press, 1986.