Facsimiles are perhaps one of the most beautiful forms of contemporary book creation. They derive their value from the riches of the book arts of our times, which can convey to us the contents of centuries-old intellectual life.

Our era has the privilege of being able to make the most precious books widely accessible by replicating them. Yet before the invention of printing, they invariably existed only as a single exemplar.

Today, it is possible to reproduce and spread the treasured books of all cultures with the all their contents and material properties; these are books that lie secure and well tended in the world’s libraries, museums and private collections.

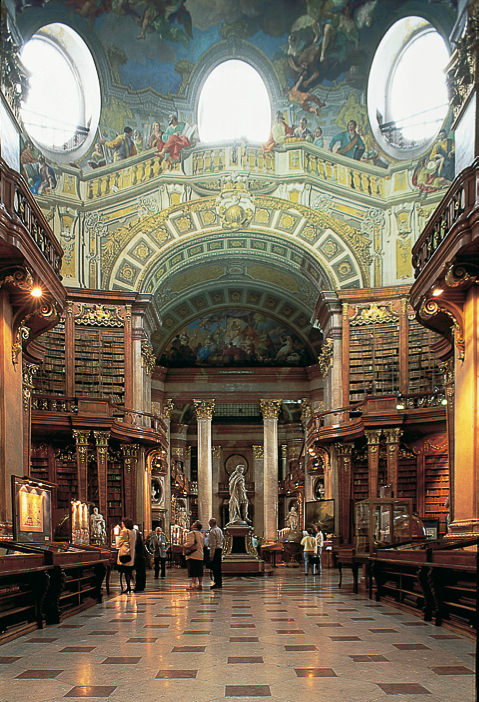

As a result, for the first time the collector, the book lover, the researcher, and the scholar hungry for knowledge are all able to build their own entire libraries of the past on which our culture rests. They can assemble a voluminous library full of valuable contents whose variety no ruler, no religious leader, not even a monastery could have ever imagined.

The facsimile is perhaps one of the most beautiful expression of contemporary book creation.

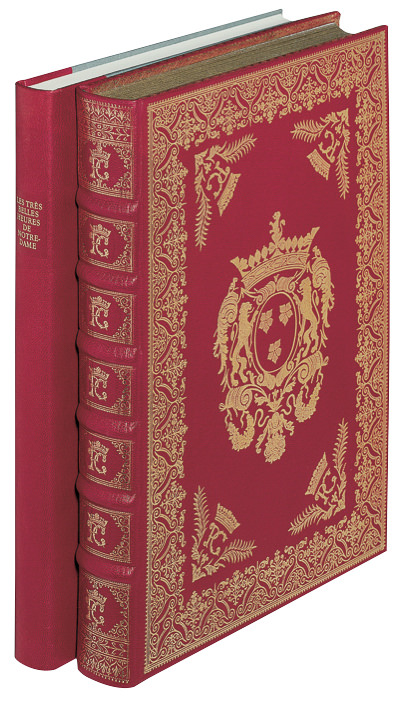

However, the facsimile is an imitation of past glories, it can only be made here and now: it does not replace the matchless original. The original’s value and beauty, its content and the artistic form it takes can be reproduced for the reader under the strictest criteria for quality conceivable, by using technologies the books’ original creators could never have imagined.

The Development of a Very Special Kind of Book

Since they are the most important chroniclers of the past, books are fundamental if we wish to understand our cultural foundations and interpret them as a guide, and foundation for our future.

We can only truly understand our intellectual, religious, literary and artistic inheritance if we know of the foundations it is built upon, and, in so doing we may rely on it, interpret it, give it meaning and absorb it both intellectually and emotionally.

Being a form of verbal communication, oral history is shaped by subjectivity and only rarely is preserved unchanged for more than one generation. At first glance, the surviving architecture of castles and palaces, fortresses, chateaux and, especially, of cathedrals, seems to be stable.

However, not only have the rigors of time altered their color and shape, also the new landscapes that now surround them may detract from their true value. Monuments and statues; transmitters of cultural identity across the eras, have suffered the same fate.

For the first time the collector, the book lover, the researcher, and the scholar hungry for knowledge are all able to build their own entire libraries of the past on which our culture rests.

After centuries, panel paintings and frescoes, as mediators of knowledge of true artistic lineage, often communicate a mere shadow of their original message.

The Art of the Book

Since they are mostly protected against light and damaging external factors by their bindings, only in books have text and images been preserved in their original glory.

The books of our ancestors therefore are our most important heritage.

Therefore, books of our ancestors are their most significant bequest to us. The culture of books, book arts, book painting and the artistic setting down of important texts have shaped the intellectual and artistic-emotional development of Europe since the Late Classical Period and the Early Middle Ages. We can rediscover these marvelous sources today in the form of facsimile editions with the addition of a scholarly commentary.

It is worth mentioning that this is not only thanks to facsimile editions, which reproduce the entirety of the manuscript, but also through portfolios, which render an overview of the most important libraries available, as performed recently by the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg or the opulent treasure book of J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. These boxed editions, an exquisite documentation of art history, also make it possible to experience centuries-old book art.

Book lovers can build a voluminous library full of valuable books whose variety no ruler, no pope, not even a monastery could have ever imagined.

How can we define this very special, modern-day form of the book; from where did it originate and how is it possible to produce such (almost) exact reproductions?

In future posts of this series, you’ll find out how this is possible and all the details of the history of facsimiles.