Hunting, particularly falconry, was a distinguished practice of the courtly elite globally across the Middle Ages. In addition to indicating noble status, hunting was also the subject of study and scientific inquiry.

The emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen was a passionate hunter. He had special interest in the art of falconry, the antique sport of hunting wild quarry by means of trained birds of prey.

The Emperor Frederick II considered the literature on the subject insufficient and decided to gather information in order to write the most comprehensive book in Western literature on the art of falconry.

The result of the emperor’s writing effort is the manuscript De Arte Venandi cum Avibus, translated as On The Art of Hunting with Birds or The Art of Falconry.

Frederick II composed the text in 1240s and dedicated the work to his son Manfred. Coupling texts and direct observation, he contended that he spent thirty years compiling this famed treatise on ornithology and falconry.

Seven manuscripts made in the thirteenth century and the Pal. lat. 1071 is preserved in the Vatican Library. This the finest of Frederick II’s versions because of the remarkable execution of the illustrations that embellish it.

The Art of Falconry: The Illustrations of a Manuscript of Natural Science

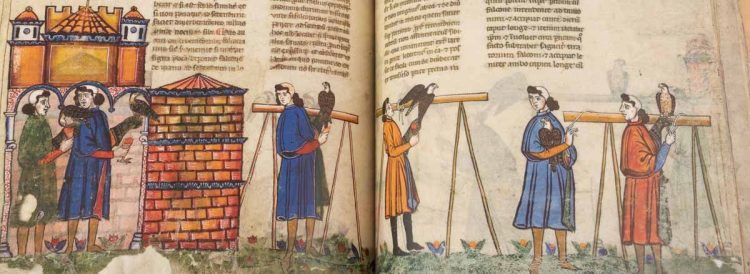

The manuscript displays two columns of text written in an elegant Gothic script and extensive illuminations in the margins.

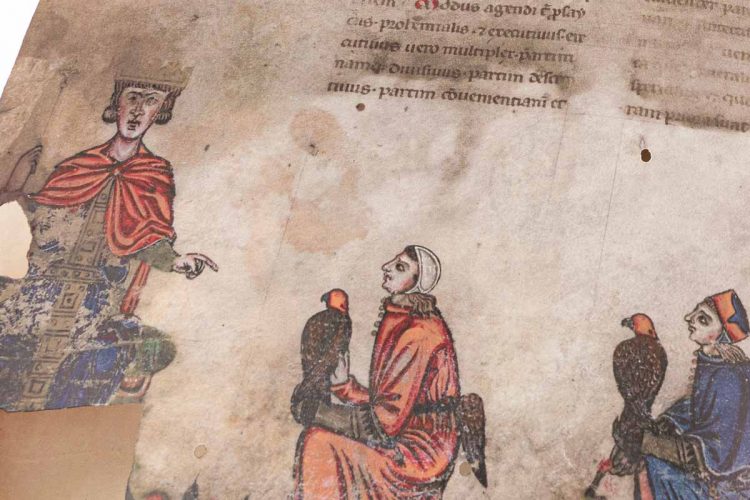

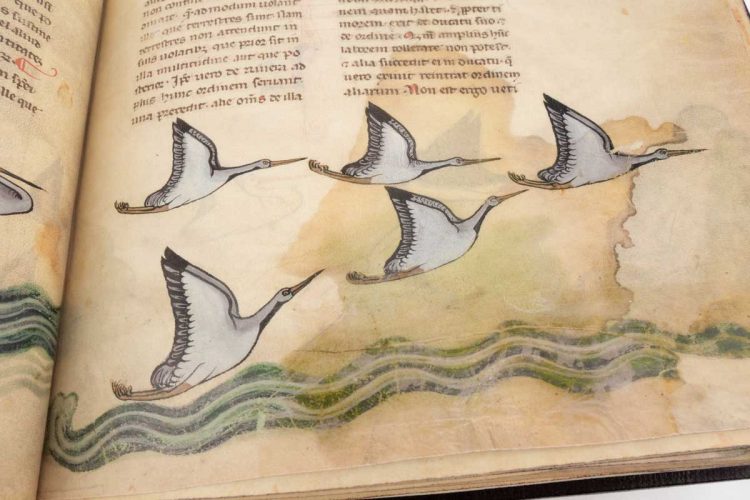

More than 900 images of birds, along with 12 horses and other animals illustrate the text throughout. Falconers and other human figures are featured hunting or engaged in other activities to instruct the reader about the techniques described in the book.

This manuscript is also notable for containing portraits of both the emperor enthroned and his son Manfred at the opening of the manuscript (fol. 1r and v, 5r) and additions made by Manfred, which are clearly marked in the beginning by notations reading “Rex”, “Rex Manfredus”, or “addidit Rex”.

Brilliant in coloring, the miniatures are accurate and minute, even to details of plumage, while the representation of birds in flight has an almost photographic quality.

Showcasing magnificent vivid colors and masterful artistry, it is a highlight of thirteenth-century illumination.

Extremely refined in its artistic quality, the codex was left incompleted. Vivid sketches of eagles, owls, storks, parrots, vultures, pelicans, swans and other species appear in the borders. The painter drew them accurately but left them without colors (fols. 94-100), providing evidence of his artistry even in the preparatory drawings.

Learning the Art of Hunting through Experience

In the fifth century, Germanic invaders brought in Europe the knowledge of falconry. After their introduction, these hunting techniques rapidly spread.

The literature on the topic is vast, starting in Europe in the tenth century with a tract by the Anonymous of Vercelli. Frederick II had knowledge of this treatise. Furthermore, he knew Arabic treatises on birds, for example the one written by the Arab falconer Moamyn.

Frederick II takes care to emphasize that his own experiments and observations were used to demonstrate and discuss the things that are exactly as they are.

These texts were important sources for the emperor; however, it is remarkable that Frederick II mainly compiled the book reporting his own experiments and observations. For example, the text explains that Frederick II covered the eyes of the vultures because he wanted to find out if birds used the sense of smell while hunting.

The emperor’s intention was to write a scientific book in order to describe the animals as they are. The meticulous illustrations clarify and decorate the encyclopedic project of Frederick II.

Ea que sunt, sicut sunt.

The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II

NEW WEEKLY VIDEO

Find our more about the Berry Apocalypse (New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.133) on our website!