Did you know that the Valenciennes Apocalypse is the oldest illustrated manuscript of the Apocalypse that has come down to us? Check out this Alumina article for more information!

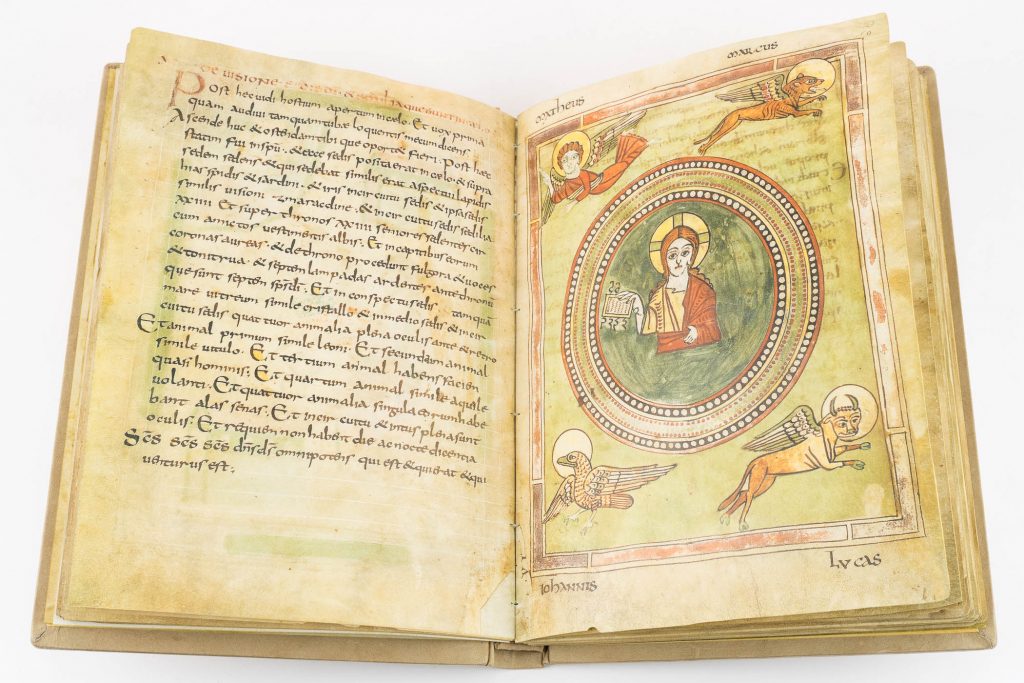

The Carolingian Valenciennes Apocalypse (Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 99) is a 270 × 202 mm parchment codex, made of 42 sheets and 38 full-page illustrations plus two drawings that were added at a later date.

Together with the contemporary Trier Apocalypse (Stadtbibliothek, Code 31), the Valenciennes codex is the oldest illustrated manuscript of the Apocalypse that has come down to us. As such, it is extremely important in the history of the Book of John’s illustration.

While the completion date of Carolingian Valenciennes Apocalypse has not been questioned for more than half a century, its place of origin remains controversial. On the basis of the calligrapher’s name, Otoltus, the earliest literature chose to attribute the manuscript to a scriptorium in the area of Salzburg, even though the same name frequently appears in other regions of the Carolingian Empire as well.

Most modern scholars, however, have followed the authoritative opinion of Bernhard Bischoff, who identified Otoltus as one of the scribes who worked on the contemporary Gotha Gospels (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 28561), thereby attributing both manuscripts to a workshop in the Middle Rhine region. This attribution may be plausible for the Gotha Gospels, as the work is documented in the library of the Mainz Cathedral in 1479 and its minuscule has clear similarities with the writing in later manuscripts from Mainz.

But the Valenciennes Apocalypse has only a few stylistic elements in common with the illustrations of the Gotha Gospels, and, contrary to what Bischoff thought, Otoltus’s script cannot be identified with that of any of the calligraphers of the Gotha Gospels. Some general affinities in the script of both manuscripts can be explained by a similar parochial influence or with the calligraphers’ parochial training.

Article written by Peter K. Klein for Alumina – Pagine Miniate.

Order your subscription to Alumina today!