Check out this interesting article written by Brownyn Stocks evaluating the importance of facsimiles in occasion of an exhibition held at Monash University.

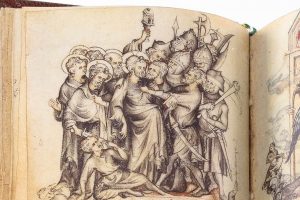

This exhibition showcases a selection of the Baillieu Library’s extensive collection of manuscript facsimiles. The selection displays copies of a range of manuscripts of various genres, dating from the 5th century through to the early 16th century. It incorporates biblical texts such as the early medieval Vienna Genesis, the 9th century Book of Kells and two 13th century Apocalypse manuscripts. Also featured are two lavishly illustrated 15th century copies of Dante’s Divine Comedy, one of which is a very recent acquisition, having been published in 2006.

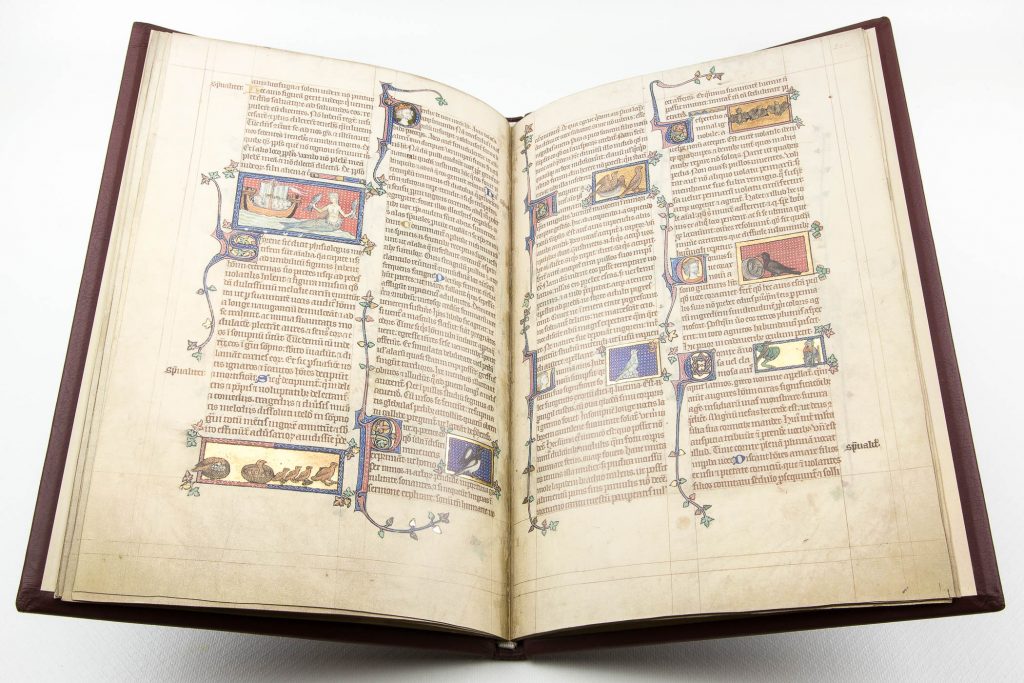

Personal prayerbooks are also a significant focus, as extensively illuminated books of hours have been an especially popular choice for facsimile production. A special feature here is the inclusion of the facsimiles of six sumptuous late medieval books of hours owned by Jean, Duc de Berry, including the famous Très Riches Heures. Fine art facsimiles are a close reproduction of the actual appearance of the original manuscript.

Thus the books copy the scale, format, colour and entire contents of the original. This means that each facsimile is the result of an extensive process of lithographic and digital photography, followed by numerous and rigorous comparisons with the original, and subsequent refinements. Each, therefore, represents a lengthy undertaking by their specialist publishers.

The facsimile of the Book of Kells, produced in 1990 by Faksimile Verlag Luzern, for example, was ten years in the making and involved numerous trips to Dublin by teams of specialists, who each time carried one of their printed folios for the purposes of close comparison.

In the creation of the facsimile of the 14th century Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, the replication of the various shades of grey in the grisaille illustrations was a particular challenge for the publishers. Sometimes the exact reproduction of the original can surprise the modern viewer. This is because we may be more familiar with the illustrations of these manuscripts in readily accessible publications that carry less precisely representative illustrations.

Techniques of Facsimile Production

It is often the colour that surprises most as the extensive processes involved in facsimile production are not normally available to book publishers. Again, the Book of Kells is a case in point where the illuminated pages sometimes strike viewers as darker than they expect. In other cases, the colours of the original and therefore of the facsimile are surprisingly brilliant. That the pigments of a manuscript like the Sforza Hours remain so vivid after more than five hundred years seems miraculous.

The replication of gold leaf is another feature that viewers of facsimiles often remark on, and there are numerous examples exhibited here where gold leaf is a major and very showy feature of the decorative program, the 12th century Ingeborg Psalter being just one such example. In facsimile production even the proportions of an uneven page are copied exactly. This means that not only are the rough, uneven edges of the original vellum copied, but so too is the damage to pages that has occurred over time.

The facsimile of the Peterborough Bestiary, for example, is bound in a copy of a Cambridge leather binding dated c.1510-15 and features roll stamps which appropriately show a series of dragons, griffins and lions.

Photography of a manuscript for facsimile production usually involves removal of its binding so that the pages can be viewed in their entirety. In some cases this can bring added benefits to the viewing public. When the Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux was unbound, for example, a special display of a page from each of the five main sections of the manuscript, instead of the usual single opening, was mounted at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and also at the Metropolitan Museum, New York. The Book of Kells, on the other hand, could not be removed from its binding because of its fragile nature and so the facsimile publishers commissioned the invention of a special device that used suction to pull the pages flat in order to facilitate photography. Removal of a manuscript from its binding can also aid its restoration.

This was the case with the Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, which, when unbound, revealed damage to the early folios and thereby facilitated their repair. While the aim of a facsimile is to provide an object that is as close as possible to the original, a major difference between the original and the copy is that facsimile technology has not been able to replicate the feel of vellum or parchment. The touch of an original manuscript often reveals an uneven texture on account of the natural properties of the particular animal skin used and also where sections of text may have been scraped away to make amendments. Vellum also has a ‘hair side’ and a smooth side, reminding the reader of the material’s origins; something that cannot be easily duplicated by technology.

Academic Use of Manuscript Facsimiles

The production of a facsimile often has numerous advantages for scholarship. The availability of the entire text and images to scholars that might not otherwise have ready access to such material prompts new research interests and facilitates close study. During the process of facsimile production, publishers also often provide access to the manuscript for scholars interested in undertaking new research on codicological features of the book as well as on artists’ techniques and materials. Facsimile publishers also normally commission a companion volume to the facsimile, which provides specialist commentary by scholarly experts. These volumes incorporate the most recent research and are an important contribution to the scholarly discourse on each manuscript.

Recent Phenomenon

The production of facsimile of manuscripts is a relatively recent phenomenon. It began in earnest in the 1970s and has increased with the development of a market for such exquisite objects. Because of their deluxe production and their publication in strictly limited, numbered editions, facsimiles are considered attractive investments by some collectors. The 1984 facsimile of the Très Riches Heures of the Duke de Berry, for example, sold out long ago and is now much sought-after by collectors. In fact, owing to the great demand to own a ‘true copy’ of the original, the publishers produced a further limited edition of the calendar pages. The rarity and fame of this particular manuscript facsimile virtually corresponds to that of the original.

While Walter Benjamin predicted that the prevalence and accessibility of the copy would diminish the precious quality or ‘aura’ of an original artwork, Michael Camille has argued convincingly that this is not necessarily the case and that, in fact, the Très Riches Heures has gained an ‘aura’ via its reproduction.

Are Facsimiles a Luxury Commodity?

Camille argued that the notion of this manuscript as a ‘luxury commodity’ has been perpetuated and enhanced by the production of a sumptuous, limited-edition facsimile. This was further emphasised by the fact that the original manuscript came to be considered so valuable that it was made virtually inaccessible to all, and was kept locked away in a safe in the Musée Condé at Chantilly. Indeed, the production of the facsimile and thereby the creation of an ‘alternative’ to viewing the original, may have been a contributing factor here since the promotional material issued by Faksimile Verlag Luzern on the occasion of its publication stated: “After the facsimile has been produced the original will be locked away forever!”

The market for these productions includes, of course, both the public and specialist library as well as the private collector. The purchase of such volumes by libraries provides scholars – and indeed all those with an interest in a particular manuscript – with the opportunity to access material not normally readily available. It could also be argued that the production of a facsimile aids the conservation of the original as scholars may use this as a tool to understand much about the manuscript without, or at least before, accessing the original.

The facsimile also provides documentation of the original that would prove invaluable were the original to be lost. The production of such volumes has also been encouraged by changes in the scholarly approach to the study of manuscripts.

In recent decades there has been a significant movement towards the consideration of particular aspects within the context of the entire book, and the relationship of text, image and decoration, together with attention to the archaeological information a manuscript may reveal, such as corrections, additions and various codicological features and alterations.

The facsimile provides the viewer with the incomparable experience of the book. Parts that are not normally reproduced in published studies can be read and examined, and each page related to its place within the context of the entire manuscript. The facsimile also allows us to comprehend more readily the size, scale, and object-ness of the manuscript. When one considers that each of these books was handmade for the enjoyment of such discerning patrons as Jean, Duc de Berry, and passed on through the hands of later collectors, often equally passionate in their attachment to the fine book, then the opportunity to observe such finely crafted close replicas offers readers of today a fascinating glimpse into their origins and history.

Acknowledgement

I should especially like to thank Pam Pryde, Curator of Special Collections, Baillieu Library, for her invaluable assistance and advice.