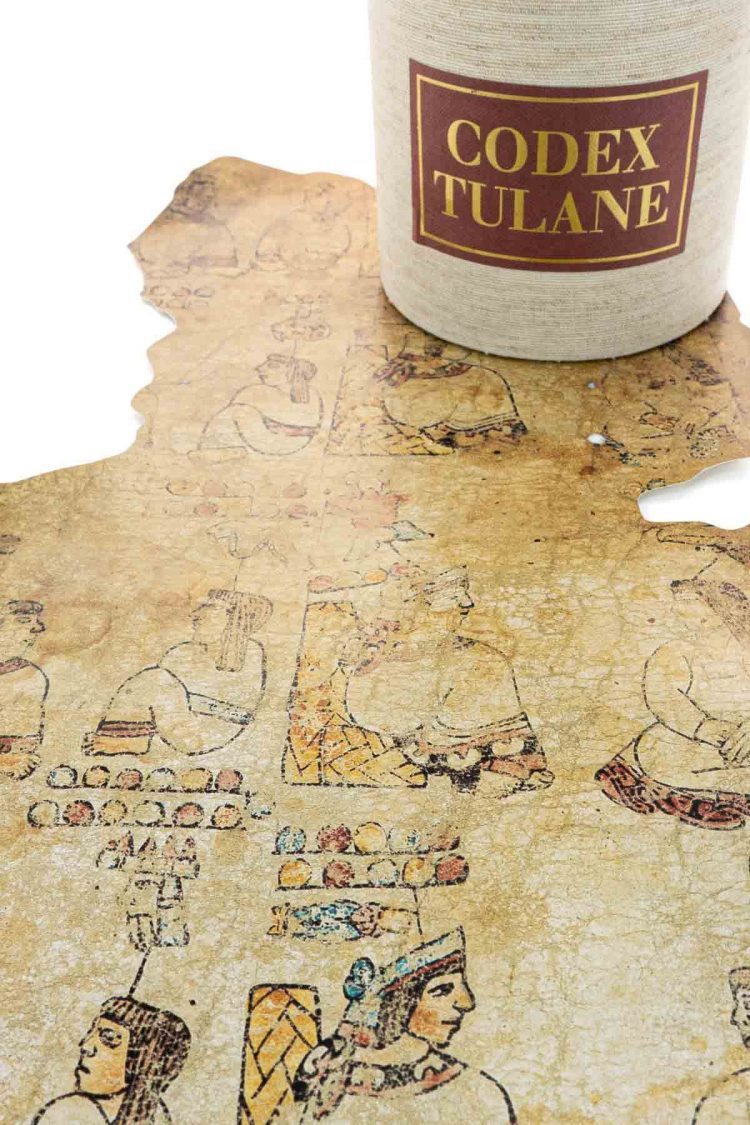

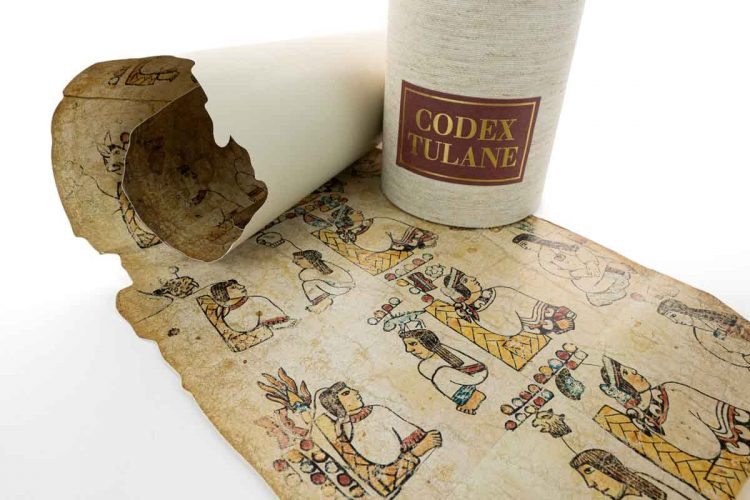

One of a few extant codices in the format of a rolled cylinder scroll, this impressive work was crafted by indigenous artists with European influences. Read on to discover never-ending story of the Tulane Codex.

Codex Tulane is a sixteenth-century manuscript from Puebla, Mexico presenting the history of two Mixtec city-states using the Mesoamerican pictographic technique. The contents include depictions of two ruling genealogies from the regions of Acatlan and Chila.

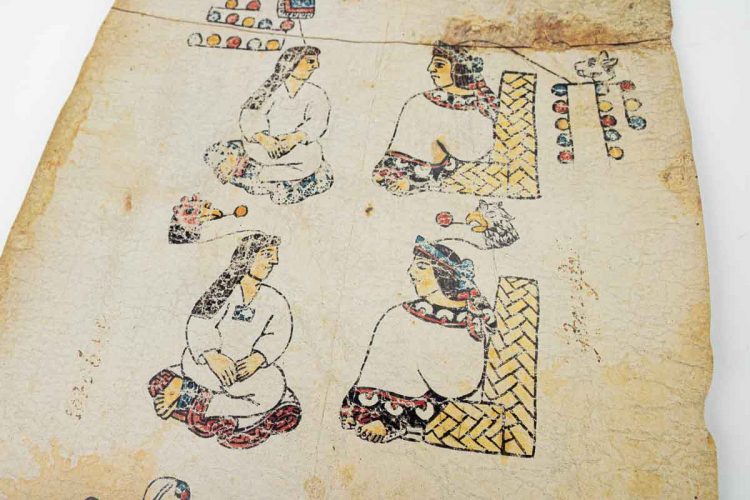

These are placed vertically along the length of the codex to establish the rightful lineage of these communities when land disputes appeared during the colonial era. It portrays 112 human figures, sixty-six male and forty-six female.

A 373.5 cm Long Genealogy

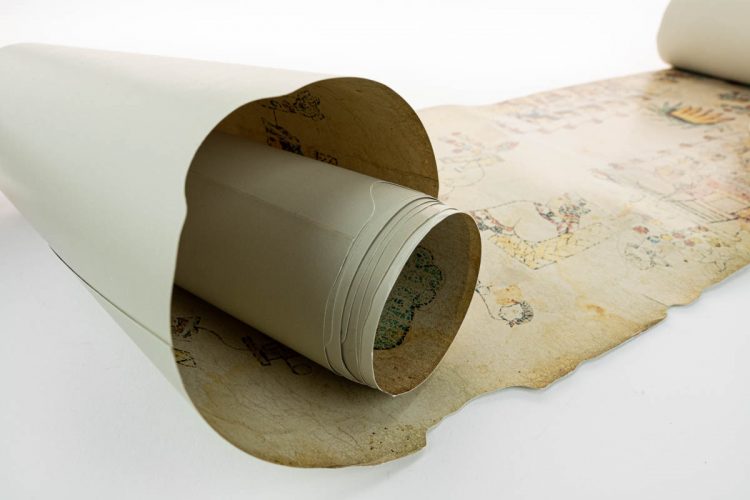

When unrolled, the scroll measures 373.5 cm in length by 22 cm wide. Thin deerskin leather covered in a light stucco surface forms the support for this work.

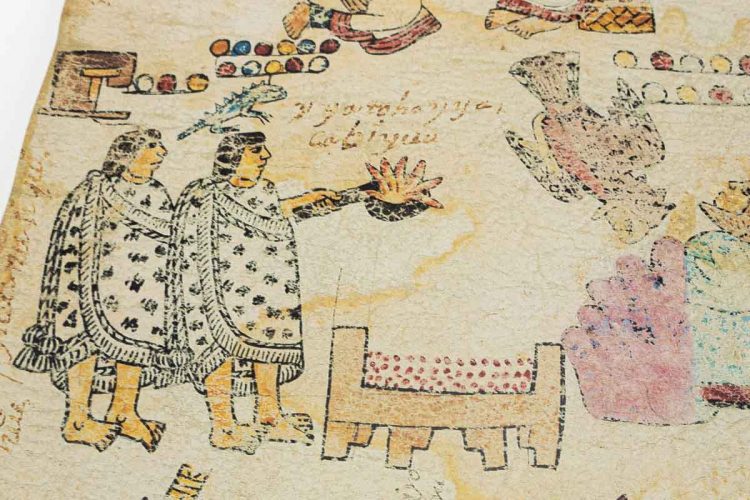

Written for indigenous and colonial audiences, the codex uses pictographs, glyphs, and local iconography to communicate dates and places of events, and denote deities affiliated with the aforementioned southwest Puebla municipalities.

The Tale of Two City-States

Created to establish the historical familial lines of the city-states of Chila and Acatlan (Toavui and Yucu Yusi, respectfully, in colonial Mixtec) in southern Puebla and northern Oaxaca, referred to as Mixteca Baja, the Codex Tulane was a tool used by indigenous peoples and the post-conquest government as documentation of legitimate territorial rights to the colonial authorities.

Each of the genealogies is accompanied by toponyms of geographical features linking the lineages to the landscape: a jewel-topped mountain for Acatlan and a river indicating Chila.

Read from bottom to top, the content of the scroll begins as many Mesoamerican histories begin, with the telling of the origin myths and ceremonies, deities, and symbolic dates.

This story-telling merges into the first genealogy representing fifteen generations of rulers in the municipality of Chila, their portraits arranged in a vertical line forming a column, each ruler sitting across from his wife. Moving vertically up the scroll, the second genealogy for the town of Acatlan begins after the first ends.

On the left is another column containing the wives’ parents, indicating deeper ancestral ties to the region. Glyphs and iconography are used to identify specific characteristics of the individuals.

Design Elements Reveal Aztec, Mixtec, and European Traditions

The Codex Tulane artists have not been identified, although there is evidence that they were indigenous, trained in local artistic traditions stemming from the Valley of Mexico and Mixteca Baja.

Features such as the leather substrate sized in lime, black contour lines for figures and objects, flat landscapes, dimensionless figures, and human heads in profile reflect strong schooling in local artistic traditions. A device of indigenous pictograph composition is missing; the use of red lines to divide up the picture plane doesn’t exist in the Codex Tulane. Instead, it contains two thin vertical lines to aid the artist in composing the lineages, male figures are placed on the right of the line and females on the left of the line.

Rendering of the human figures and how they are seated reveals a blending of pictorial conventions from Aztec and Mixtec traditions, but also suggests European influences.

Many of the women are shown seated in what is known as the Aztec woman’s pose where the woman is seated on the fullness of her skirt with her legs tucked under her, torso facing the viewer, and feet off to the side.

The male and other female bodies are portrayed in the Mixtec tradition with the body in profile and feet flat on the floor. Pre-conquest portraits represent the eyeball as being in the center of the eye, some of the eyes in the codex are illustrated in this manner. Other eyes are pictured with the eyeball in the front of the eye, a technique of European artists.

Proportions of the priest figures appear to be of colonial influence, with the height-to-head ratio being 1:6 rather than the Valley of Mexico established the ratio of 1:4.

The colors used in the Codex Tulane, when compared to those of other manuscripts of the Mixtec region of northern Oaxaca and southern Puebla, are subdued and lighter in tonality, indicating that the artists had exposure to European painting. One scholar has related the artistic elements of the codex to the Ñuiñe style sculpture and ceramics of the region displaying similar iconography and glyphs. Scholars believe this work may have been copied from other pictorial manuscripts that are no longer extant.

In Good Shape, Even After Multiple Owners

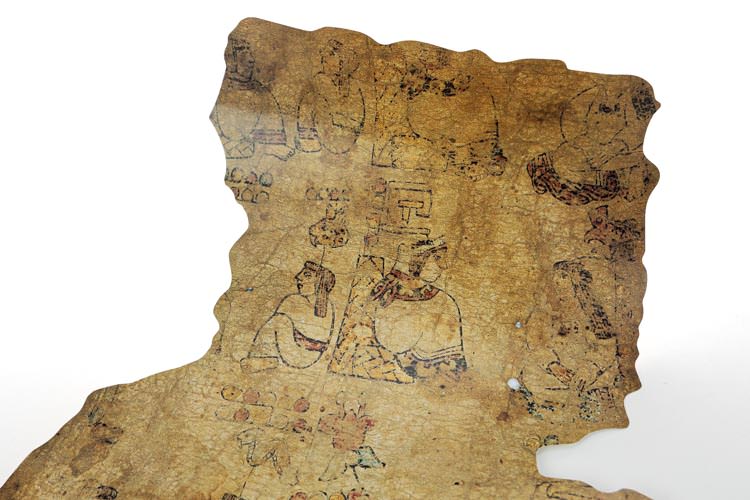

Considering its age and history, the Codex Tulane is in good condition. Six hides were used to construct the support for the codex. A white lime-based sizing was applied to the hides to create the painting surface. In some areas, the sizing is thinner than in other sections.

Illustrations and the glossary appear only on the obverse side. European script on the reverse side dating from the late sixteenth century were written directly on the hide. Traces of other inscriptions in the same hand appear in other sized places on the reverse.

There are a few tears and small holes in the codex. Stains can be seen in some portions of the work. Markings on the reverse reveal that text was erased sometime during the sixteenth century.

On the back of the third hide, there are two orange circles where sealing wax was applied to affix official colonial seals in the eighteenth or nineteenth century when the document would have been rolled, sealed, and then submitted to the court as evidence.

Overall the colorants are mottled and some of the blue pigments have flaked away. The main palette is comprised of red, blue, brown, orange, blue-green, pink, and a pale purplish tone. Red and blue are the most prominent colors, with these two colors being used in headgear and garments of the men and women.

Hide and Seek: From Repurposing to Academia

The manufacturing of the Codex Tulane in post-conquest Puebla is well documented. What is unknown is where the codex was kept between the end of the sixteenth century and the early nineteen century.

In 1801, the codex was altered and used to authenticate a land claim involving the town of San Juan Ñumi, just south of Chila. At this time, the map and the illustrations of other ancient residents were added to the Chila genealogy. Also added was the Mixtec glossary, the only alphabetic text contained in this codex.

The codex was repurposed in the early nineteenth century by a neighboring community to establish land entitlements. At this time a glossary, a map, and more images were added.

Until 1912 it was housed in the church of San Martin Huamelalpan in Oaxaca, Mexico. It was stolen from the church and by 1929 was in the possession of Spanish-Mexican merchant Felix Munro. It was then sold to Alfred Onken in Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca.

It was acquired by the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University in 1932, then transferred in 1970 to the Latin American Library at the Howard-Tilton Library, Tulane University.

Special Thanks to Miranda Howard, MALS, MA Professor Emerita, University Libraries.

NEW WEEKLY VIDEOS

Find our more about the Book of the Hunt (Bruxelles, Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique, Ms. 10218) on our website!

Find our more about the Werden Psalter (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Ms. theol. lat. fol. 358) on our website!