It is a truism of medieval art history that virtually all Ottonian art betrays the influence of Carolingian art, and this is demonstrated above all in the art of manuscript illumination. The Gero Codex is a remarkable witness to how an Ottonian painter received the Carolingian heritage so valued by the painters of his age.

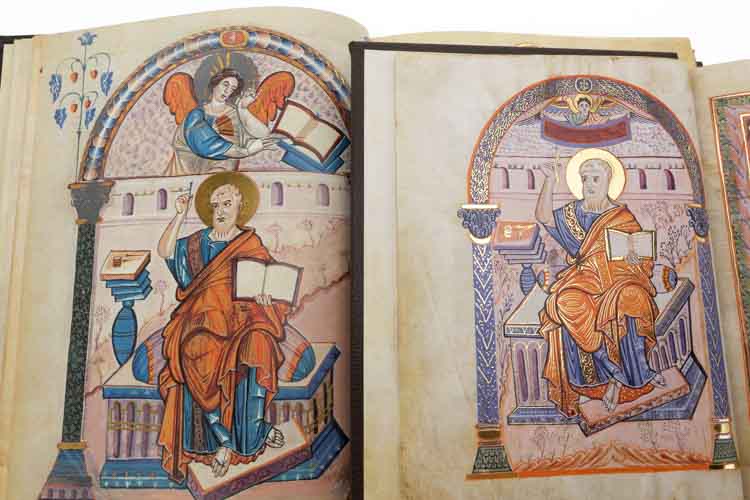

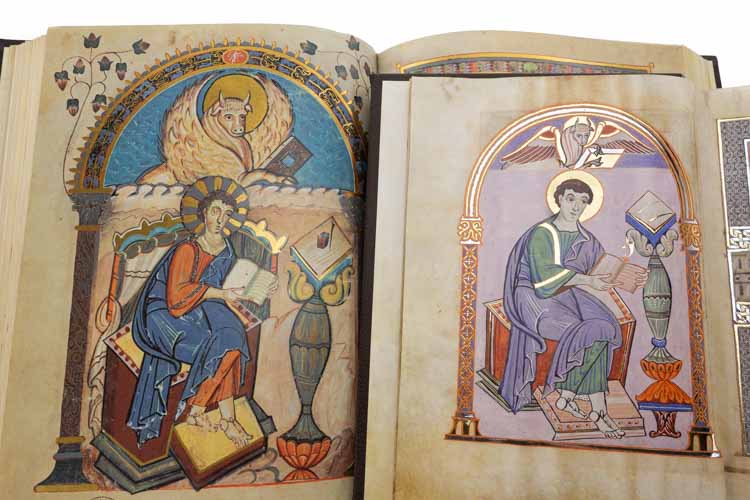

The Carolingian manuscript that provided the inspiration is the Lorsch Gospels, a deluxe Christian biblical manuscript produced at the court scriptorium of Charlemagne or his son Louis the Pious. Five of its miniatures served as models for miniatures in the Gero Codex, a sumptuous early Ottonian Christian liturgical manuscript.

The Lorsch Gospels (named for the royal monastery where it was housed early in its history) comprises the four biblical accounts of the life of Christ presented in biblical order. Portraits of the four evangelists—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—are dispersed through the book, each introducing the writer’s Gospel text. Also prefacing Matthew’s account is an image of Christ in Majesty—the enthroned Christ of the Second Coming.

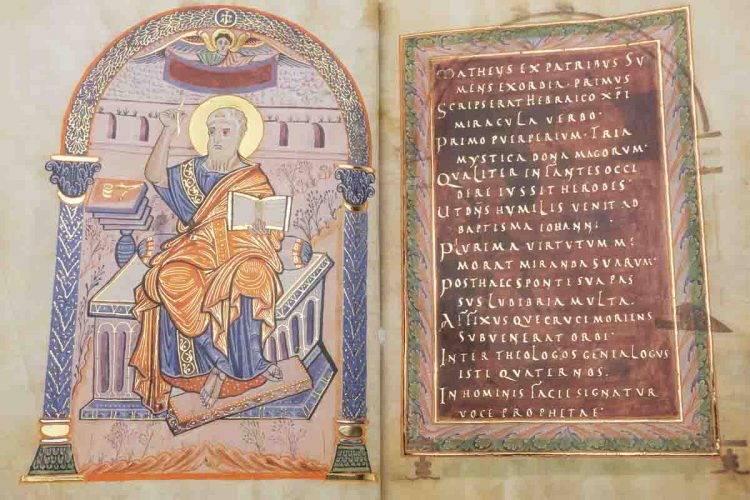

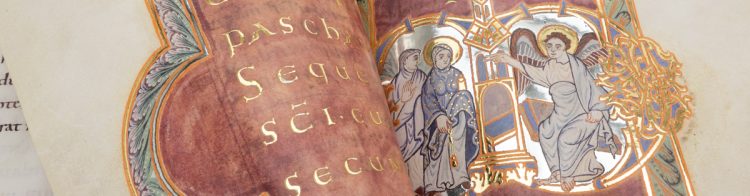

The Gero Codex (named for its patron) is a book of readings excerpted from the biblical accounts of the life of Christ arranged for use at Mass, the Christian rite in which bread and wine are consecrated and consumed. It includes portraits of the four evangelists, each facing a sumptuously painted text page, and a miniature of Christ in Majesty—all grouped at the beginning of the book and all based on the corresponding painting in the Lorsch Gospels.

The Gero Codex was created more than a century after the Lorsch Gospels. Despite that temporal distance, the compositions of the Ottonian paintings—that is, their content, the general placement of the figures, and the architectural settings—are manifestly based on the miniatures in the Lorsch manuscript. The general aesthetic is similar between the two books, with a strong emphasis on grandeur. Still, the Ottonian artist transforms his models to meet the emerging artistic preoccupations of his time.

The Evangelists Reimagined: From Symbols to Icons

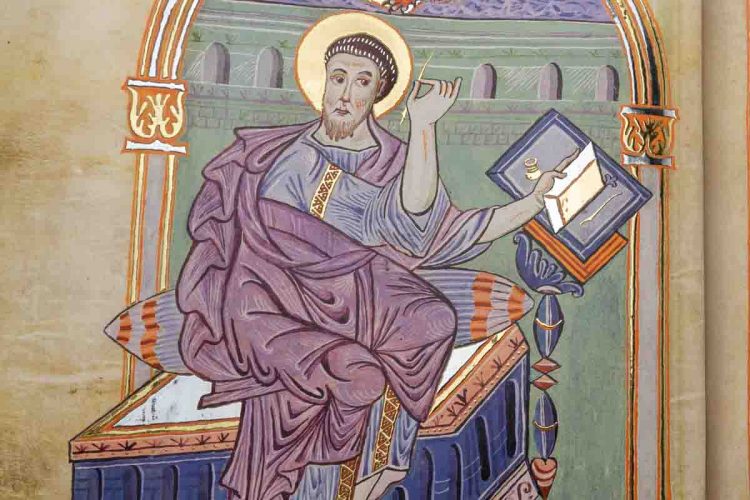

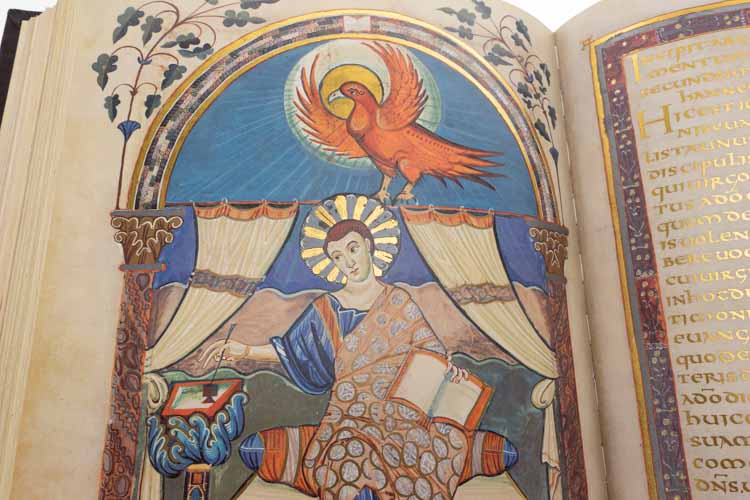

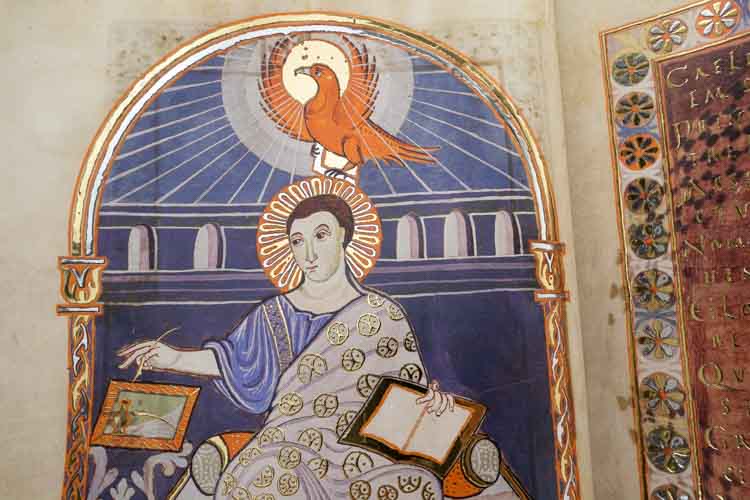

We do not know how the painter of the miniatures in the Gero Codex knew the Carolingian precedent, but there can be no doubt that he did. The orientation and activity of each evangelist in the Ottonian book copies the Carolingian manuscript: Matthew seated frontally and examining his pen (or stylus?); Mark, his legs in profile, twists to inspect his pen; Luke holds his text in both hands; John reaches to his right to dip his quill.

At the same time that the Ottonian artist quotes the compositions of the Carolingian antecedent, he subtly changes things to increase the monumentality of the already substantial figures. Saint Mark’s architectonic throne –see below– appears in front of one of the columns purportedly establishing the “setting” for the scene, pushing the figure of the evangelist into the viewer’s space and commanding our attention.

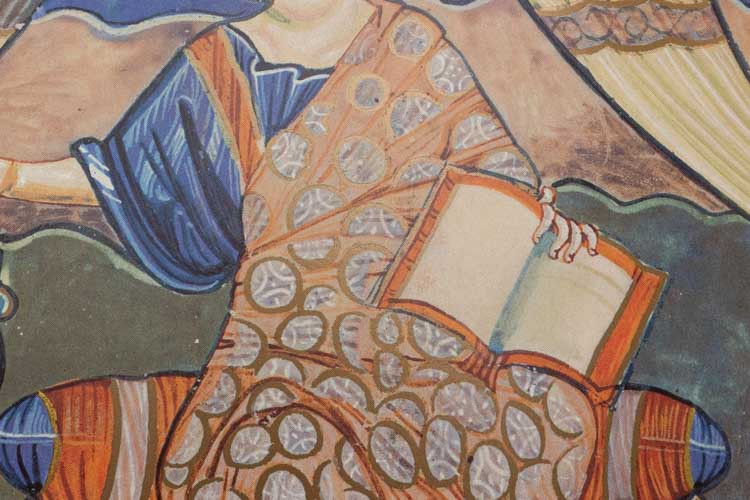

The Ottonian artist was also keenly aware of the page’s decorative potential. For example, the Ottonian painter transformed the circle motifs on Saint John’s cloak in the Lorsch Gospel into more intricate patterns rendered in gold, enhancing the design on the two-dimensional surface of the parchment.

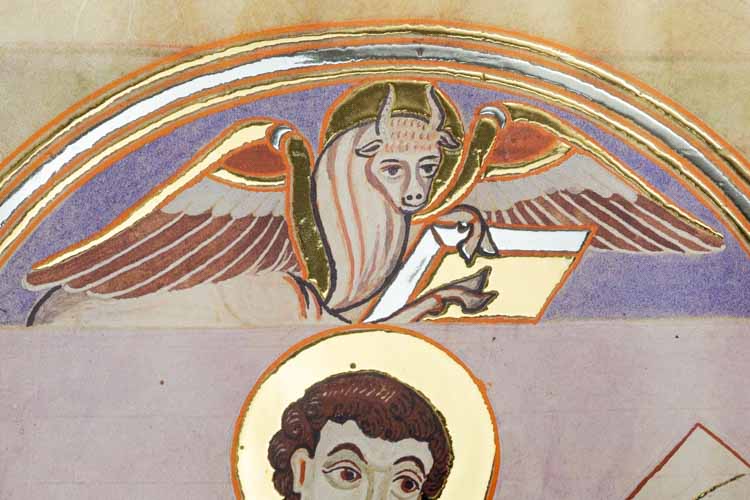

The Ottonian artist also transformed the evangelists’ symbols and their interactions with the writers. The symbols originate in the vision of the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel of four creatures with the faces of a man, a lion, an ox, and an eagle, each with wings. In the Christian tradition, those creatures came to be associated with the four evangelists: the man with Matthew, the lion with Mark, the ox (or calf) with Luke, and the eagle with John.

In the Lorsch Gospels, the half figures of the evangelist symbols seem to occupy the space of the lunette defined by the arch of the architectural setting. The Ottonian artist has reduced both their size and their roles. They appear as mere symbols, not actors in the drama.

Christ in Majesty: Carolingian Elegance and Ottonian Grandeur

The Ottonian illuminator’s reductionism (not to be confused with simplification) is especially apparent in the Christ in Majesty. He includes only the monumental Christ—quoting the singular gesture of joined thumb and ring finger—and the four evangelist symbols, eliminating the angels and the text. The circular aureole is moved in front of and extends beyond the painted frame. This Christ confronts the viewer more forcefully than his Carolingian predecessor.

There can be little doubt that the Ottonian artist of the Gero Codex revered the Carolingian model he emulated. At the same time, he created an illuminated manuscript that expresses his own day’s aesthetic and spiritual concerns.

Mayr-Harting, Henry. Ottonian Book Illumination: An Historical Study. 2 vols. London: Harvey Miller, 1991.