Professor Shirin Fozi explains why she found handling the newly acquired Hebrew facsimiles in the University of Pittsburgh’s library to be transformative and why the physical presence of the facsimiles in the library proved vital for her seminars.

One of my constant goals as a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, where I taught from 2013-2022, was to incorporate more Jewish art into art history and museum studies courses. Given my own lack of specialized training, this always felt like a daunting task, and yet over time the urgency of expanding our view of the Middle Ages to better reflect the different ethnic, cultural, and religious groups who lived in premodern Europe became increasingly clear.

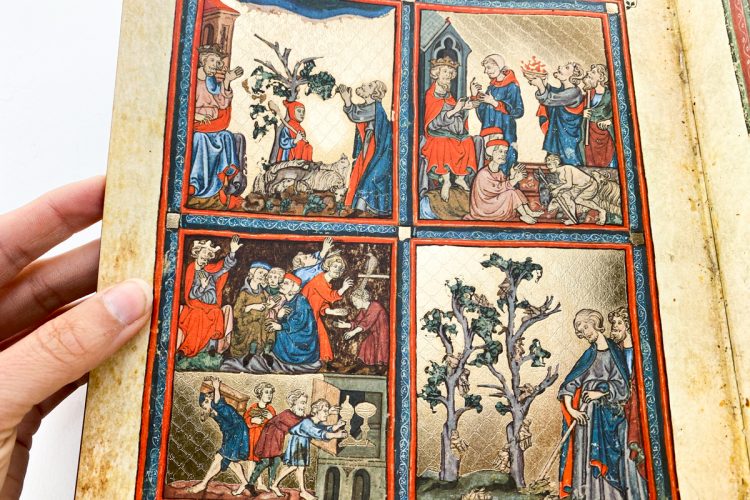

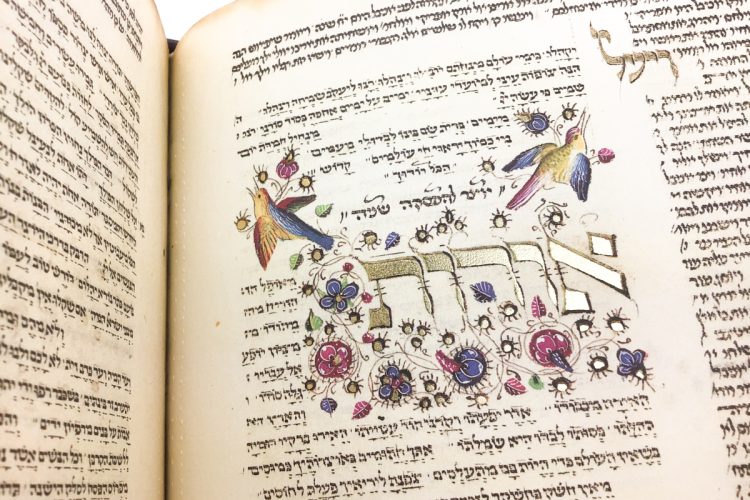

About seven years ago, as I was browsing the teaching resources in our University Library System (ULS), I became aware of Pitt’s rare facsimile of the first Darmstadt Haggadah, published in Leipzig in the 1920s. Together with my students, I soon became fascinated with the book’s rich colors and lively scenes of men and women feasting, studying, and even bathing together. It wasn’t long before I found myself applying for grants to expand our collection, and luckily my colleagues in ULS and also Jewish Studies were eager to support this undertaking.

Enriching Pitt’s Rare Book Collection

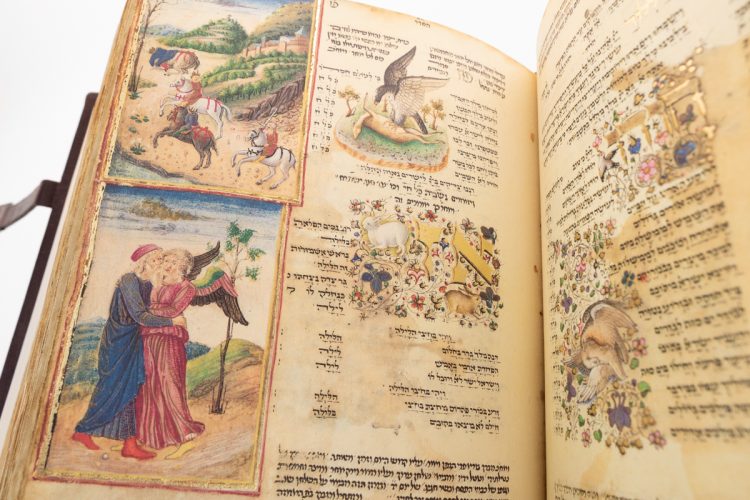

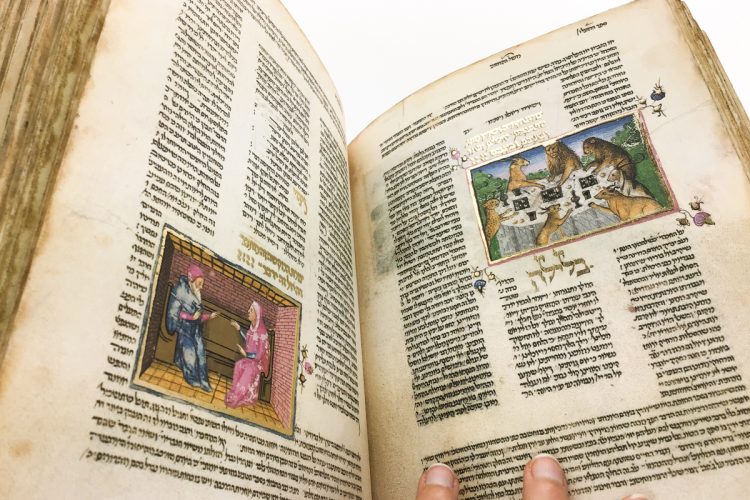

In 2019 we were able to add several significant Hebrew manuscript facsimiles to Pitt’s rare book collection, including high-quality copies of the Worms Mahzor, the Parma Psalter, and the Rothschild Miscellany. These arrived just in time to be included in the checklist for the exhibition course I was planning for the Museum Studies program; they were also the focus of a hands-on study day in March 2020 with Adam S. Cohen from the University of Toronto that brought together students, faculty, and librarians.

I found handling the library’s new Hebrew facsimiles transformative: my uncertainties about what I didn’t know, or hadn’t yet learned, were soon replaced with genuine curiosity about the books themselves. These are fascinating codices, and the facsimiles allow us to experience their scale and complexity directly, turning the pages and looking closely, whether individually or in dialogue with colleagues.

During the workshop, one of the librarians read aloud the Yiddish words on folio 54r of the Worms Mahzor, which offer a blessing to the one who carries the book to the synagogue.

The facsimile – which replicates the magisterial size of the codex – communicated the context of the verse with wonderful clarity, as we all imagined the labor involved in lugging such a treasure from place to place. The facsimile became a powerful proxy as we pondered further on the provenance of the original manuscript, its miraculous survival through pogroms and wars, and its current home in the National Library of Israel, Jerusalem.

Facsimiles as a Resource in Challenging Times

Days later, Pittsburgh was plunged into lockdown amid the COVID-19 pandemic. At first it felt like a tremendous irony that the facsimiles were suddenly inaccessible, so soon after we had celebrated their arrival on campus and their wonderfully haptic ability to communicate historical knowledge. Yet as the crisis progressed, and we all adapted to the new realities of an increasingly virtual world, the physical presence of the facsimiles in the library proved to be of vital importance for my seminars.

The Museum Studies exhibition seminar was converted to an online format, and by October 2020 the library staff was able to welcome students to Special Collections where we built the exhibition by studying, photographing, and filming the books – all while observing new safety protocols with gloves, masks, and social distancing. The exhibition put facsimiles in dialogue with digitized manuscripts, taking special note of the instances where manuscripts that were available to us in facsimile – including several of our new Hebrew highlights – have not yet been digitized by their respective institutions.

Even in the cases where digitized versions are readily available, such as the Golden Haggadah in the British Library and the first Darmstadt Haggadah, students were quick to point out that there was something special in the experience of holding books, placing them on tables, and carefully turning the pages. The fact that our library visits had to be so carefully planned, and limited to so few participants, only heightened the value of the facsimiles in the eyes of our students. We took care to document and communicate these precious experiences in the online exhibition, as best we could.

Students’ Appreciation of Hebrew Manuscript Facsimiles

The exhibition project embraced the full span of Pitt’s facsimile collections; the Hebrew manuscripts only comprise about 25% of the show. Throughout the Fall 2020 semester, however, I was struck by how often the students commented that the Jewish books were their favorites.

Some of this was because of the sheer wonder of the codices themselves: the sparkling gold of the Parma Psalter, the amusing vignettes of the Rothschild Miscellany, and the lively narratives of the Golden Haggadah were all a source of endless delight. Beyond this, however – and given that many of the facsimiles in the show are ultimately glorious objects – I think the students were also simply surprised by the sheer richness of medieval Jewish art. They already expected to see Christian manuscripts, made for emperors and cathedrals, filled with stunning designs – but none of the students had any inkling that equal treasures survive from Hebrew communities, both Sephardic and Ashkenazic.

One undergraduate poignantly remarked that the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre – which had taken place only two years before our exhibition went live, just two miles up the street – placed an obligation on everyone at Pitt to learn more about Judaism, both past and present, to highlight Jewish history, literature, and art across our curriculum, and to share this knowledge with others. I am heartened to think that the Hebrew facsimiles in ULS not only allowed us to engage in such efforts last year, and in our exhibition, but will invite future generations to do similar work for many years to come.