After eight and a half centuries this liturgical book, profusely decorated with shimmering gold and silver, is almost untouched by time. A new facsimile edition by Quaternio Verlag Luzern takes us closer to the perfection of its Romanesque illuminations.

This story begins in the bustling city of Hildesheim shortly after the year 1000. Bishop Bernward was highly revered among the monks of St. Michael’s Abbey, an imposing Romanesque church just outside the city walls — for years, Bernward had commissioned churches and fortifications to defend the town against attacks by pagan Normans. When he passed away in 1022, his faithful monks decided to support his canonization by crafting one of the most precious manuscripts of their time, namely, the Stammheim Missal.

The monks of St. Michael’s Abbey put so much skill and endeavor into their work that both their beloved Bishop and the volume they produced became immortal: Pope Celestine III proclaimed Bernward a Saint in 1193, and the Stammheim Missal still shines as brightly as on the day it left the scriptorium.

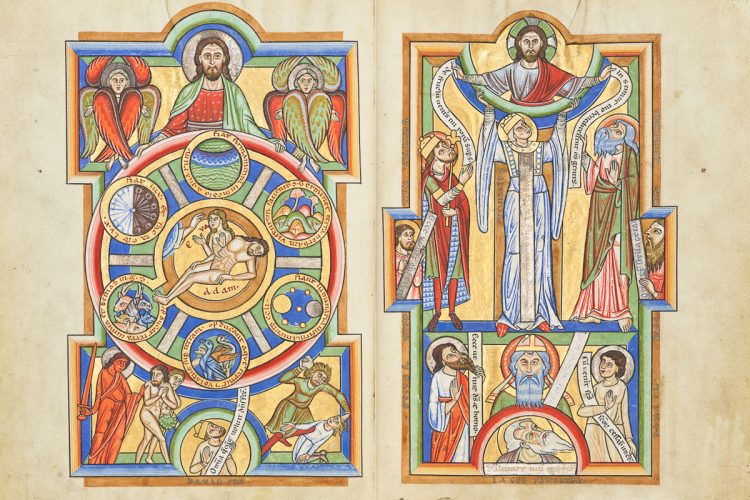

The distinctive features of the Stammheim Missal’s decoration are its large golden surfaces and the geometrical ornate frames with impressive religious illustrations. These testify to the deep spirituality of the 12th century and to the illuminators’ powerful devotion.

To protect its marvelous miniatures from possible damage, this gem from the German Romanesque period is now safely stored in the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and this year a facsimile edition by Quaternio Verlag Luzern offers a close-to-real experience of the manuscript, together with commentaries by renowned medievalists.

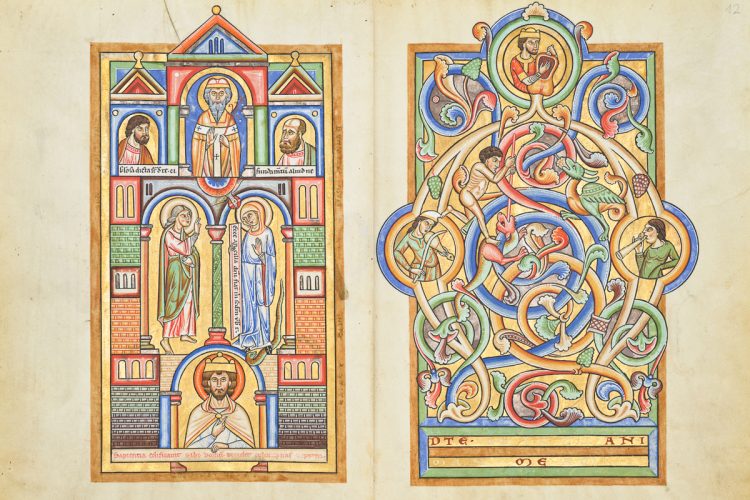

But what makes this volume one of the most astonishing examples of medieval illumination? One could state that the Stammheim Missal’s value lies in the perfect symmetry of its geometrical frames, or in its bright colors, or in its characters, whose intense gaze makes them come alive to readers — the truth is that Hildesheim’s monks masterfully blended all of these elements into a rich and captivating account of the main events of Jesus’ life.

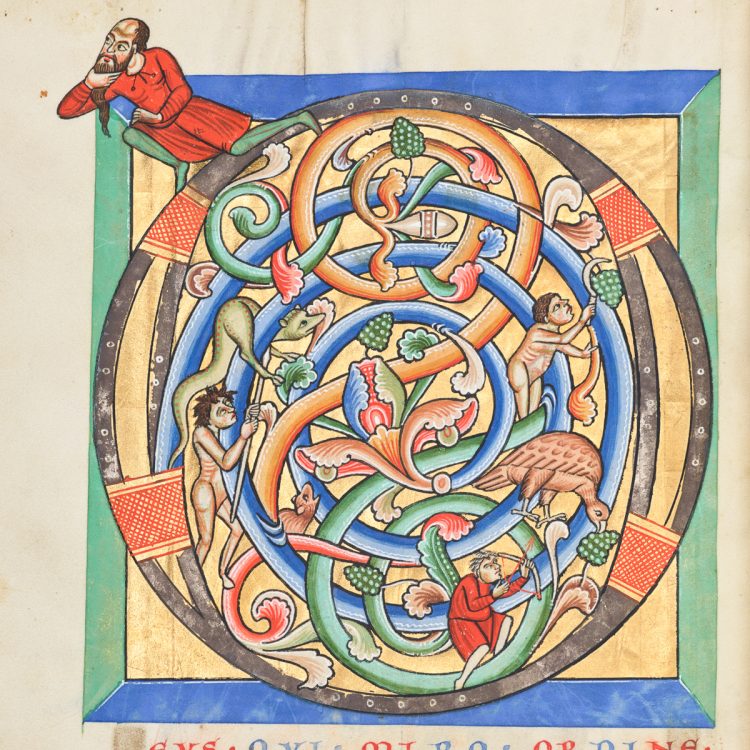

While the Missal’s practical purpose was to list the songs and prayers performed during mass throughout the liturgical year, its illustrations are pure beauty. They include twelve full-page miniatures, three richly adorned incipit pages, ten half-page inhabited initials, twelve calendar pages, and twenty-nine pages with painted arcades.

Out of all the inhabited initials in the manuscript, one, in particular, catches the eye: it is letter B on fol. 58r., decorated with brightly colored vines, along which various figures are harvesting and producing wine.

The frames are not merely decorative but act as a design element, dividing the page into image fields which are often cross-shaped, allowing the illuminators to enclose within the frames a great variety of scenes from the New and the Old Testament.

From the 12th century up to 1803, the monks of St. Michael’s abbey kept this precious book safe. When secularization led to the closing of the monastery in 1803, the Missal became the property of the Fürstenberg-Stammheim family and was kept in the Stammheim castle in Cologne, where it remained until 1997, when the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles finally purchased it.

This thousand-year story, which began in medieval Germany, could end up in your hands. Check out the facsimile edition by Quaternio Verlag Luzern to lay your eyes on one of the 480 copies of this incredibly intricate work of art.