Innumerable facial expressions, the birth of manga, sparkles of silver and gold, ancient magical legends…There are thousands of reasons to love the picture scrolls made in the land of the rising sun. Here are ours.

1. The Voice of Women in Kana Diaries

During the Heian period in Japan (from 794 to 1185) many diaries, both public and private, were written by men. But while these texts contain statements that reflect the judgments and emotions of their authors, there is in them much less of a sense of the living voice than in diaries written in the Japanese kana syllabary.

This is why Ki no Tsurayuki (872 – 945) found a new means to express himself when he took on the guise of a woman, and opened his Tosa Diary (Tosa nikki) with the sentence:

I write this thinking that I, a woman, might also try my hand at one of those things the men write, that they call a diary

This medium—the kana diary—made it possible for him to voice his longing for the distant capital during an appointment in the provinces, and to give vent to his grief after a beloved daughter died in that remote area. Kana prose (kanabumi) was the only form of writing really suited to the production of a “voice” that might call up a reader’s sympathies.

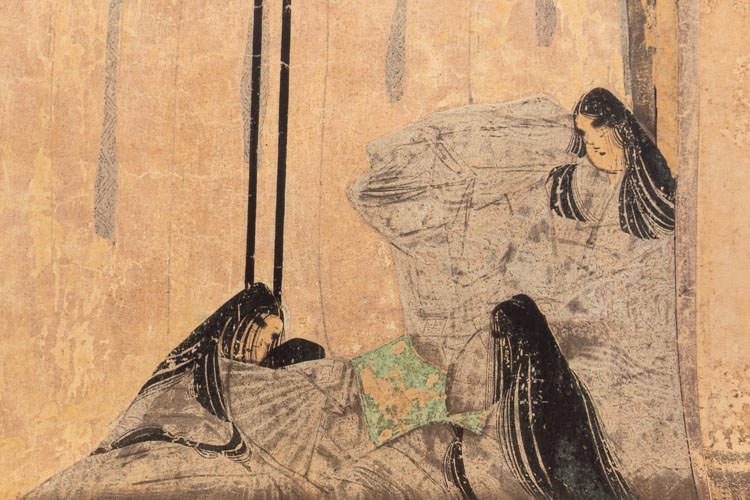

Murasaki Shikibu (973-1019?) composed a record of the joyous events surrounding the birth of a prince to Empress Shōshi, in whose service she was employed following the death of her husband after only two years of marriage.

This cautious, quiet, and rather shy woman found herself in the midst of the dazzle of court life, a major figure in Empress Shōshi‘s cultural salon. The greater her renown as an author grew, the more she began to lament her own inherent inability to feel at home in the brilliant world of court life, and the more she tried to hide behind the mask of an unremarkable lady-in-waiting unaccustomed to the ways of the world. Today, Murasaki Shikibu is considered the greatest kana prose stylists of her age.

2. The Countless Human Expressions in the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba

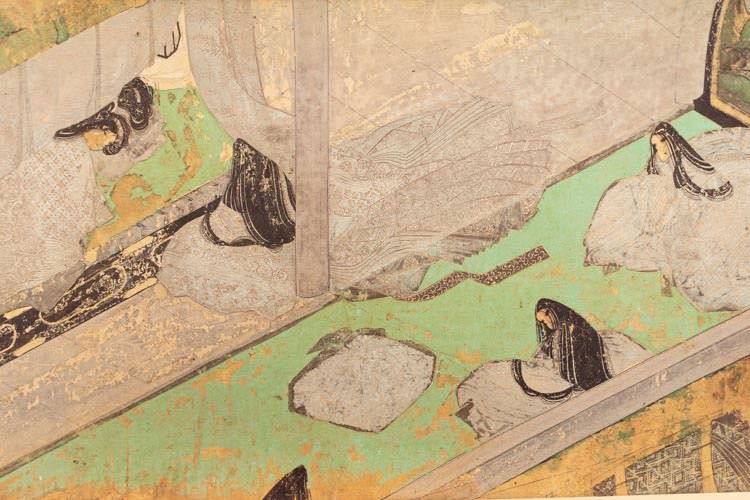

As you may have noticed in the photos, many of the over 400 characters appearing in the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba scrolls are commoners. These characters are secondary to the story, but they are crucial to the extraordinary staging of the scroll’s composition.

The Ban Dainagon Ekotoba has often been referred to as an Encyclopedia of Human Expression because each face that appears in the scroll has a distinct expression.

When compared with the understated characterization in the Genji Monogatari Emaki and the exaggerated expression in the Shigisan Engi Emaki, the characters of the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba appear the most natural of the three. The subtle, detailed technique uses short lines to create rich and varied expressions that reveal facial movement and even the tension between muscles and skin.

The expressive characters boldly sketched within the carefully planned composition seem so real that the viewer almost expects to hear the voices of children arguing, of women weeping, and of commoners in despair.

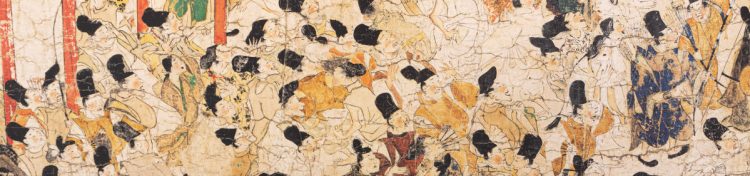

3. The Rage of Fire in the Heiji Monogatari E

The first scroll of the Heiji Monogatari E is considered by many art historians to be the finest example of a battle scene in all of Japanese art. While several hundred warriors abduct the retired Emperor and his young sister, forcing them into an ox-drawn carriage, some inhabitants jump into a well hoping to escape the flames; many of the women of the court leave only to be trampled by horses and men.

Clouds of ominous black smoke, spatters of red pigment and ink, and forked tongues of flames explode from the palace.

The text of the scroll concludes with a passage describing the desperate attempts by members of the court to learn of the fate of the retired Emperor.

“The noise of their horses and carriages rushing back and forth was like thunder, and greatly did it resound both in heaven and on earth.”

Did you know that director Kinugasa Teinosuke transformed the opening scenes of the painting into a fast-moving cinematic expression of panic and disorder in his movie The Gate of Hell?

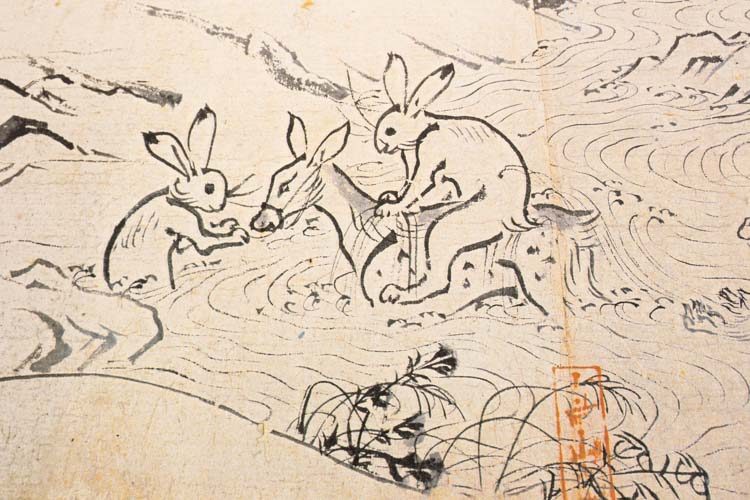

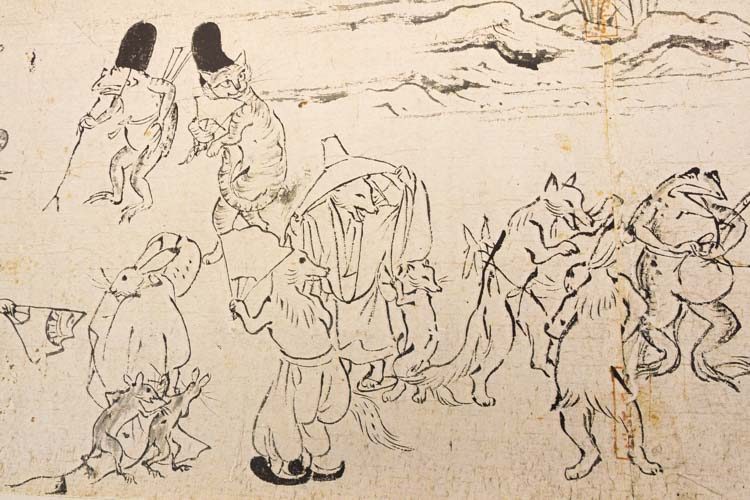

4. The Games of Frogs and Rabbits

As a result of new findings, the content of the Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga—considered by many to be the origin of Japanese caricature—was determined to include an incredible amount of scenes featuring animals playing and dancing as if they were human. Our favorite scenes are a sumo match between a rabbit and a frog; a game of go (checkers) between a rabbit and a monkey; an arm-wrestling match between a monkey and a rabbit; a high-jump contest between a rabbit and a monkey; a horse race depicting the riders, the start of the race, the monkey’s rule breaking, and his fall from the horse; a game of kickball played by a rabbit, some monkeys, and a frog. And what scenes do you enjoy the most?

5. Empress Shōtoku’s Call for Peace

In year 764, following Empress Shōtoku‘s orders, hundreds of wooden pagodas, each containing a Buddhist prayer for peace, were distributed in temples. These works of art, known as Hyakumanto Darani, represent the earliest known use of woodblock printing in Japan and one of the first recorded examples of printing in the world.

6. Clouds of Silver and Beaches of Gold

The Gengi Monogatari Emaki uses ryōshi (decorated paper) that is ornamented with extreme luxury and elegance. Paper of almost square shape is dyed with coloring materials, prepared with a formal sketch, printed using wooden stamps, flecked with gold or silver leaf that has been cut or torn into various sizes, or sprinkled with long, thin gold- or silver-leaf strips or with gold or silver dust to represent a beach or clouds and mist.

The Gengi Monogatari Emaki provides the only example of an illustrated narrative handscroll with such luxuriously ornamented paper, and the characters and the dyed and color paper onto which they are written form an ornamental whole that is hard to break apart.

7. Monk Myōren’s Levitation Powers

At the start of Scroll One of the Shigisan-engi Emaki, maids and handymen shelter their eyes to gaze up at the sky. Something utterly astounding has happened: a golden bowl has rolled out of the doorway of the storehouse in the courtyard and has started to lift it, swaying weightily, up into the sky. Tiles fall, and before long, the storehouse has risen up into the air away into the distance. A monk, known as Myōren, is believed to be responsible for these strange phenomena…

But who was Monk Myōren? Although historical evidence is scarce, a document surviving from the 12th century confirms that Myōren actually existed in the first half of the tenth century.

The fact that the Buddhist scriptures in his possession included also esoteric texts such as the Shingonkyō suggests that although he was basically an ascetic recluse, he was also familiar with disciplines such as shugendō, with its emphasis on the acquisition of magical powers. The eclectic nature of his beliefs is indicated by the very varied nature of the Buddhist figures that he enshrined in buildings of the temple.

The text passages are drawn from commentaries written by Akio Donohashi, Ueno Kenji, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, Taizo Kuroda, Sano Midori, and Ikeda Shinobu.