Today’s Alumina Article deepens the figure of Isabella d’Este Gonzaga, the Reinassance princess legendary for her art collection and education.

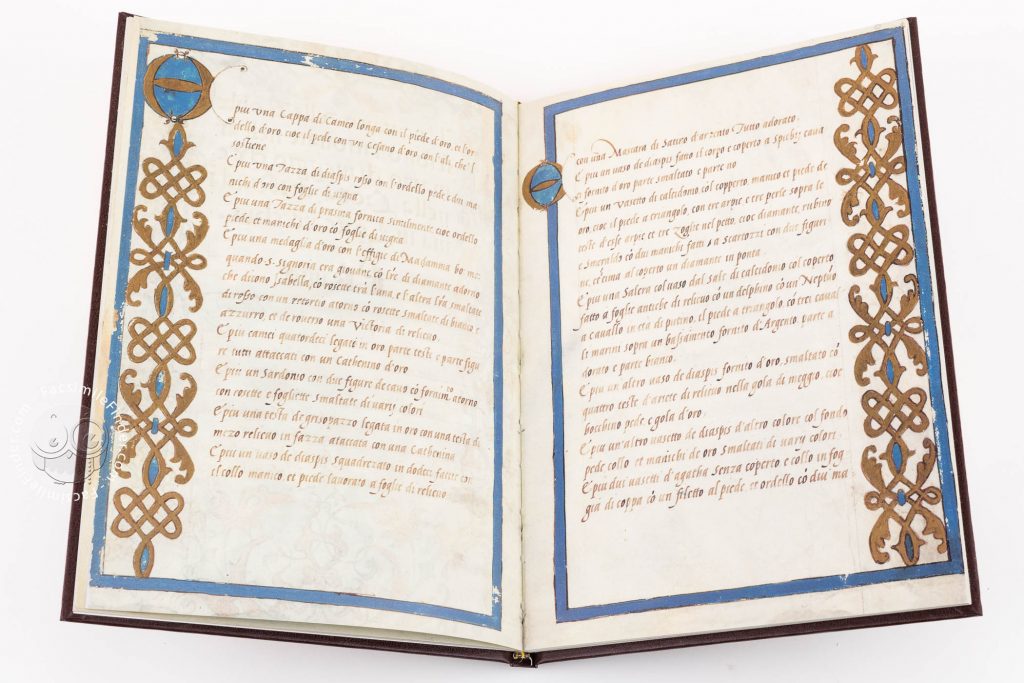

In his review of the exhibition La Prima Donna del Mondo (Vienna, 1994) for “The Burlington Magazine”, Clifford Brown pondered whether, having spent so much on art, Isabella d’Este Gonzaga would have approved of her treasures – enlisted in the Stivini Codex – being made accessible to the public-at-large when she barely had only shown them to a few privileged scholars.

The fact that only a few people were lucky enough to visit the small studio in the Ducal Palace in Mantua can be inferred from the instructions Isabella left relatives and courtiers. Every time the Princess left the city, concerning the consultation of the manuscripts or the way in which they were to handle the keys to open the Grotta, where paintings by Mantegna, Correggio, Perugino, and Costa hung above the wooden inlays carved by the Mola brothers.

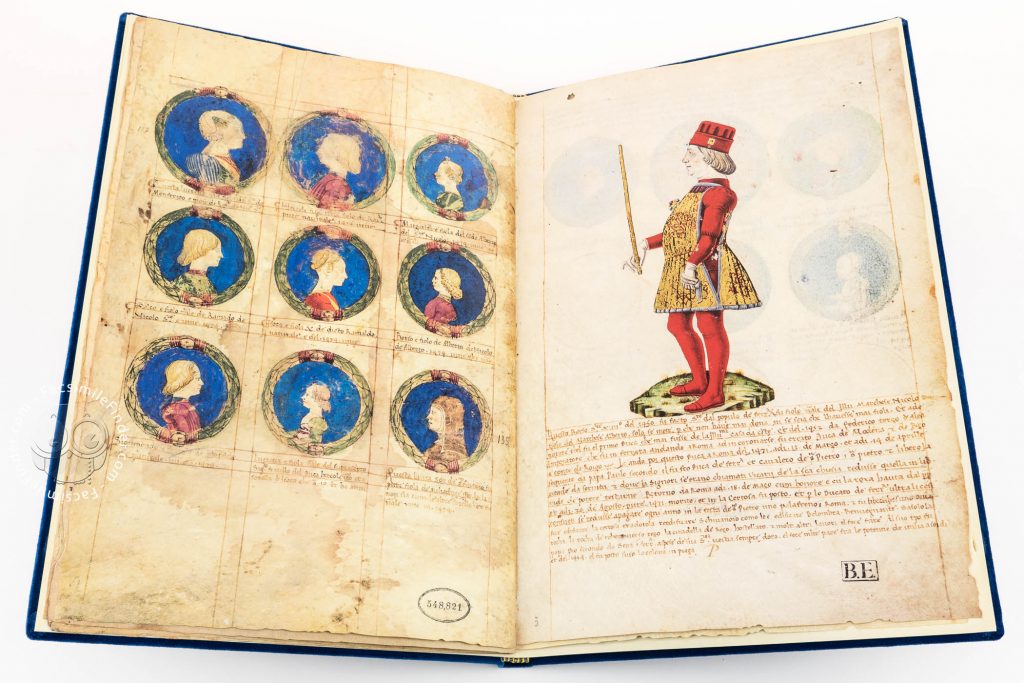

Among the several manuscripts commissioned by Isabella, take a look at the Genealogy of the d’Este Princes.

Still, if Isabella’s reputation as a well-educated and cultured woman had spread through a large part of Europe, if some of her works of art were envied by the most powerful men the task of entertaining others on earth, if many sought to be invited in the small studio or the secret garden, it is reasonable to suppose that, despite her cautious restrictions, her art collections were known by many. Moreover, from the moment Isabella officially entered Mantua in February 1490 as Francesco II Gonzaga‘s new bride –

sitting atop a triumphal carriage followed by fourteen coffers crammed with a rich dowry (Roberta Iotti)

– until her death in 1539, many scholars, artists, men and women of letters, merchants, art dealers, powerful people, relatives, and friends were the Madame’s guests.

Article written by Mauro Bini for Alumina – Pagine Miniate.