Around 1260, the Catalan mystic Ramon Llull set out to convert Muslims to Christianity with mathematical diagrams – he ended up with a logical method that influenced philosophers for generations.

When Giovanni came back from the 2019 Frankfurt Book Fair with a suitcase full of facsimiles and a mind whirling with ideas, we promised to keep you updated on the upcoming facsimile editions. Today, we’re focusing on a peculiar facsimile he spotted in Millennium Liber‘s booth that caught his eye because of its cartoon-like structure, with speech bubbles surrounding characters’ heads – it is Ramon Llull’s Breviculum, to be published in Spain in 2020.

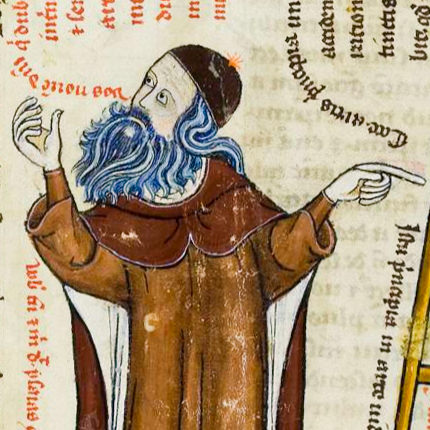

How can something so modern-looking come from the year 1321? Who was the “bearded philosopher” Ramon Llull, and why was a manuscript dedicated to his life and thought? We did some research, and here’s what we found.

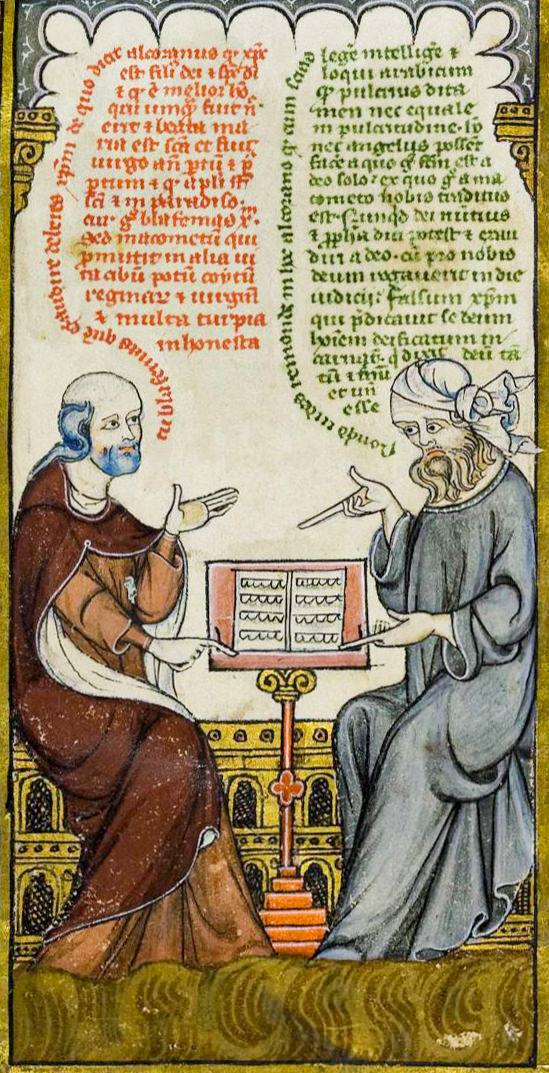

Born in Palma, Kingdom of Majorca, around 1232, Ramon Llull lived his early years as a troubadour, and even wrote a manual of chivalry, while learning Arabic thanks to the large Muslim population in Majorca. At around 30, a mystic vision of Christ on the cross urged him to give up courtly life and focus on missionary work. His knowledge of Arabic helped him in his numerous trips to North Africa, where he attempted to convert Muslims to Christianity. But this is not why he went down in history!

While his efforts with the Moorish population didn’t seem to work – legend says he was stoned to death in what is modern-day Algeria – the complex logical methods he used to prove the superiority of Christian dogmas had an impact on later philosophers, not least on Leibniz. What he strove to do was reduce all existing knowledge to first principles and organize them in mathematical diagrams (the Ars magna).

Although he spoke – and even taught – Arabic fluently, his religious enemies on the other end of the Mediterranean didn’t seem to take him seriously. The University of Paris, however, accepted him as a professor between 1310 and 1311 even without a teaching degree, and here’s where he met Thomas Le Myésier, the pupil who would become so passionate about his philosophy that he devoted an entire manuscript to it: the Breviculum.

Le Myésierbecame convinced that the royal French court could not do without Llull’s philosophy, and after his death, he had the Breviculum compiled, together with an explanation of his reasons:

Firstly, to show the origin, in other words, from whom and how this art, and the other arts and writings by Raimundo, emerged. Secondly, to encourage good deeds, in the knowledge that doing to often stimulated the spirit through the sense of vision.

The manuscript’s title, “Breviculum“, points to a principle Le Myésier valued as much as reason itself: brevity, because, in his own words, “modern men like brevity above all things” (moderni gaudent brevitate considerabilium). This is why the entangled life of Ramon Llull takes up only seven pages of the 45-folio volume.

Could this also be why the smooth and elegant Littera Parisiensis script extends to the pictures themselves, both as conceptual notes and as speech bubbles? We cannot know the intended reason, but one thing is sure: the illustrations, with their defined colors and crisp black lines, remind modern viewers of a “bande dessinée”.

The resemblance to comic books isn’t the only modern thing about the Breviculum: its author Le Myésier focused on Ramon Llull’s experiences as the events in the life of a contemporary person rather than as hagiographical scenes. Before 1300, biographical series of a secular nature were completely unknown. What was also unprecedented is the painting style, which does not compare to any other illuminated manuscript in contemporary France.

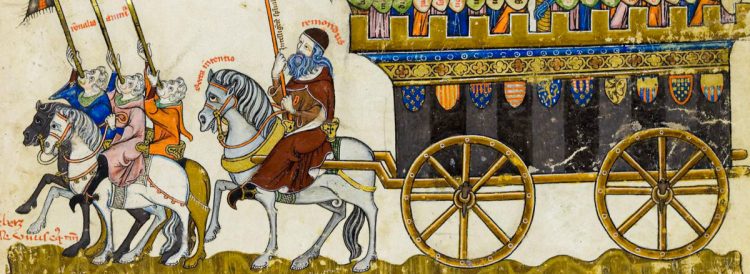

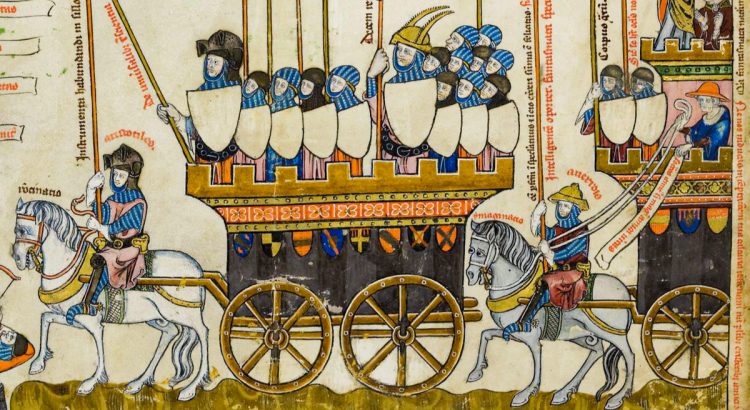

An allegorical miniature on folios 6v/7r shows Aristotle and Averroes mounted on horseback, each pulling a chariot loaded with troops and headed toward the “tower of lies” to liberate Truth, held prisoner by the vices (represented by the Saracens). The first chariot has fifteen knights, representing the basic concepts of Aristotelean logic: five predicables and ten categories. In Averroes‘ chart ride a cardinal and other prelates.

The troops led by Llull are divided into two groups, portraying the axiomatic foundation of his art (absolute and relative principles). Before the chariot, three heralds with trumpets announce and proclaim God in the form of Holy Trinity.

Le Myésier‘s support for Llullian philosophy went beyond a pupil’s admiration for his professor – he believed that “Raimundo”, with his Ars magna, could help solve the dilemma that gripped European universities around the year 1300: the relationship between theology and philosophy, a conflict ignited by the new translations of Aristotle’s works. By publishing Llull’s diagrams, Le Myésier sought to prove that a system in which Christian faith and scientific knowledge mutually supported one another in the quest for truth was possible.

A few months ago, we stumbled upon an early printed book that also reminded us of us of modern comics: the Apocalypsis Johannis.