Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent was not just a powerful statesman, but also a sensitive and emotional poet: in the Muhibbî Dîvânı manuscript, his verses are encased within an intricate artwork made of 370 different flower and plant patterns. Scroll down to see the video!

In the mid 16th century, Constantinople had reached its zenith as a bustling capital of arts and culture. Kanunî Sultan Süleyman‘s imperial art societies had attracted dozens of talented painters, bookbinders, and goldsmiths from every corner of the Ottoman Empire as well as recently annexed European territories. In the city’s medreses (colleges), boys of all ages were learning to count, read, tell the position of the stars, and use philosophical thought to make sense of the world.

Promoting the arts was like breathing to Sultan Süleyman, who composed poems both in Turkish and Persian in a style known as diwan, under the pseudonym Muhibbî (true friend, lover). Since 1557, his imperial painting studio had a new head painter: Kara Memi, who combined both traditional and innovative motifs in his artworks, including naturalistic flowers and abstract geometric patterns.

Muhibbî, meaning lover, is Sultan Süleyman’s penname, and Dîvânı stands for an ancient Ottoman poetic tradition.

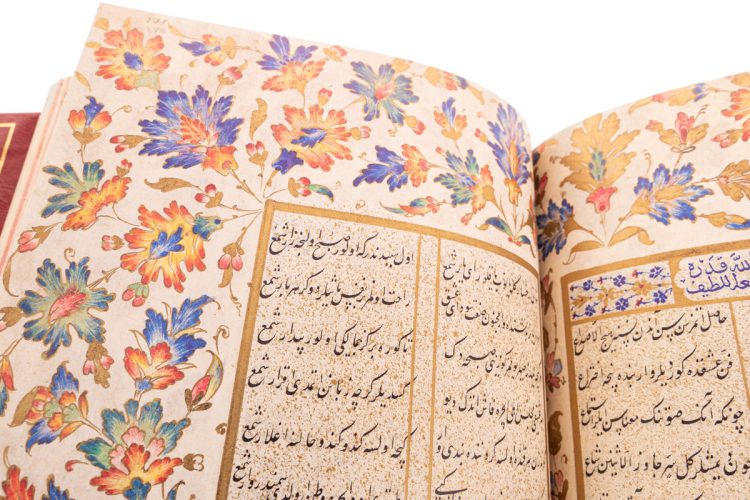

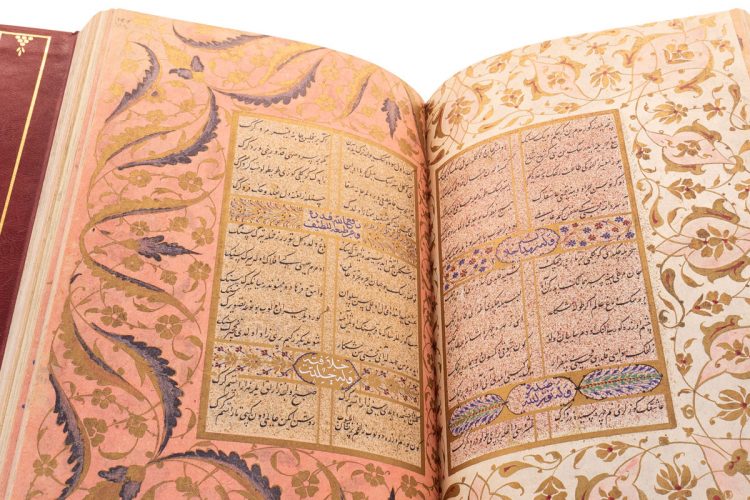

Kara Memi crafted the perfect framework for the Sultan’s love poems, as we can see today by leafing through the facsimile edition of the Muhibbî Dîvânı, a manuscript that is regarded as one of the greatest 16th-century Ottoman artworks.

When the volume was published in 1566, Constantinople was a city of roughly half a million inhabitants with more than thirty royal gardens and two hundred florists’ shops. Surplus fruit and flowers were not only sold in stands but also given as gifts on special occasions such as births and marriages.

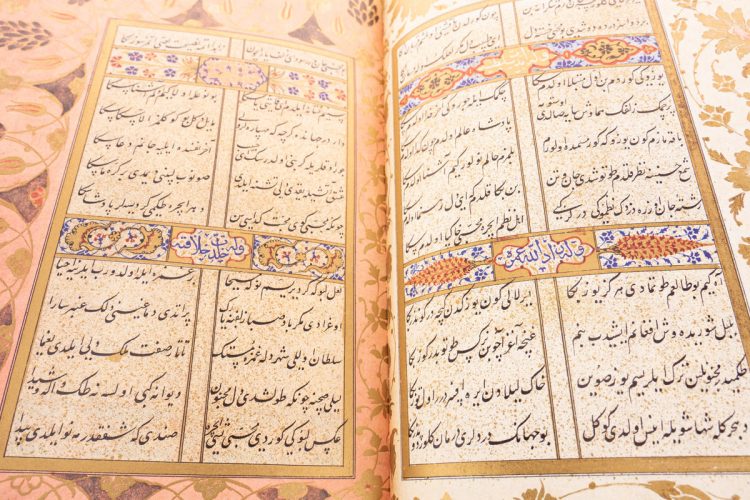

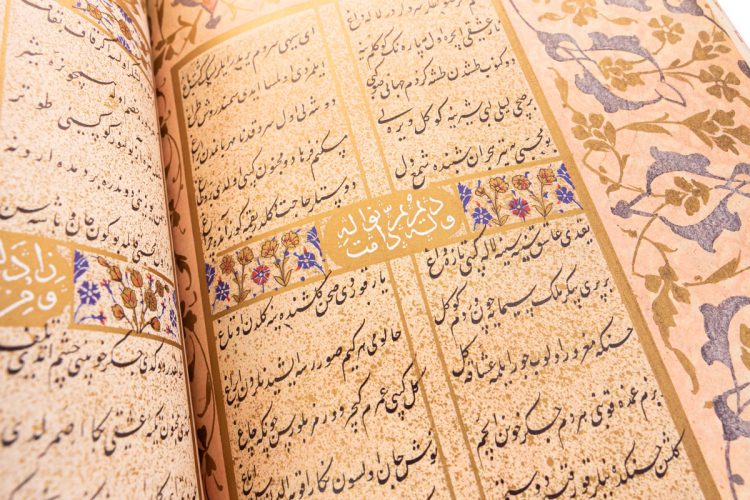

Meanwhile, in the imperial workshops of Topkapı Palace, decorative arts were also blooming: silk fabrics, ceramic ware, and wall tiles were filled with motifs of cypresses, pine cones, carnations, tulips, and roses. Yet, in the Muhibbî Dîvânı Kara Memi surpassed himself by filling 1552 decorated panels with 370 different patterns based on real and imaginary plants and flowers.

Kara Memi showed great mastery of gold, silver, and colors in their pure and diluted forms, in such detail that the hues cannot be captured exactly in photographs, and are only discernible by a trained and careful eye.

In the Arabic text encircled by Kara Memi’s creative innovations, Süleyman the Magnificent relinquishes his role as sultan to worship a young woman as tall as a cypress, with cheeks as red as roses, whose value is as great as the entire Ottoman Empire. Following the tradition of diwan poetry, the Sultan becomes his loved one’s servant and accepts the suffering and sacrifice caused by her neglect.

The narrative fiction of his verses has the power to dismantle social roles because beauty can only be achieved through love and devotion and by giving up all powers. In diwan poems, loved ones never treat their admirers with kindness or even respect: the Sultan’s face becomes the ground on which the woman can walk, and her home is the imperial palace where Süleyman serves her.

In his poems, Süleyman the Magnificent prefers being a servant of his loved one than being a sultan to the world.

Although the loved one never returns his feelings, she possesses the greatest quality an Ottoman sultan can show, that is, justice. Süleyman the Magnificent, who was regarded as a virtuous, brilliant, and trustworthy ruler, uses words like justice, gift, forgiving, and mercy to describe the object of his admiration. But suffering does not matter to Süleyman the Magnificent, because mortal love is the means to achieve true, religious love.

For some more Ottoman manuscript art, check out our virtual walk through 16th-century Istanbul and our journey on the footsteps of Sultan Suleyman’ troops in their 1534 Iraqi campaign. Are you ready to see Baghdad, Tabriz, and Aleppo like they were almost 500 years ago?