Francesco’s Offiziolo is one of the earliest evidence of the fortune of Dante’s Divina Commedia in that it refers to the work at its early stages when it was still being written. Want to know more? Read on!

Until the early 2000s, Francesco da Barberino was known for his role in the production of the Documenti d’Amore (Barber. lat. 4076), an encyclopedic work composed between 1309 and 1313, while Francesco was living his life as an exile in Padua. In modern days, a major interest was taken in this work, not only because it is the oldest work preserved in duplicate copies: one completed and one without the latin commentary and the miniatures not illuminated; but also because in f. 63v Francesco makes one of the earliest reference (known to date) to Dante’s Inferno stating:

Questo [Virgilio], Dante Alighieri in una sua opera che s’intitola ‘Commedia’ e tratta, fra molte altre, di cose infernali, presenta come proprio maestro […]

In the Documenti d’Amore several references were made to a work created by Francesco da Barberino himself: the Offiziolo which, however, had never been accounted for until 2003, the year in which the manuscript was recovered by chance. This recovery opened a brand new chapter in terms of knowledge of the linguistic and artistic culture of Duecento-Trecento Italy.

The Officiolo of Francesco da Barberino is a true jewel in terms of the concept, quality of the craftsmanship, richness of the decor, the painstaking attention to detail, and for the ample but skilled use of gold. But it also plays a fundamental role in the understanding of the Italian culture of the early Trecento, hotbed of Italian Renaissance whose most emblematic figures are identified with Dante and Giotto.

Part of a private collection, the Officiolum was probably created between 1304 and 1309, while in exile in Padua where its author hanged out with Giotto, who at the time was busy with the painting of the Scrovegni Chapel. Around the same time Dante was giving life to one of the most famous pieces of Italian literature: the first Canto of the Inferno (Hell) of the Divine Comedy.

Both Giotto and Dante are influences that can be pinpointed as major influences in the iconographic and textual content of the manuscript. Let’s see how.

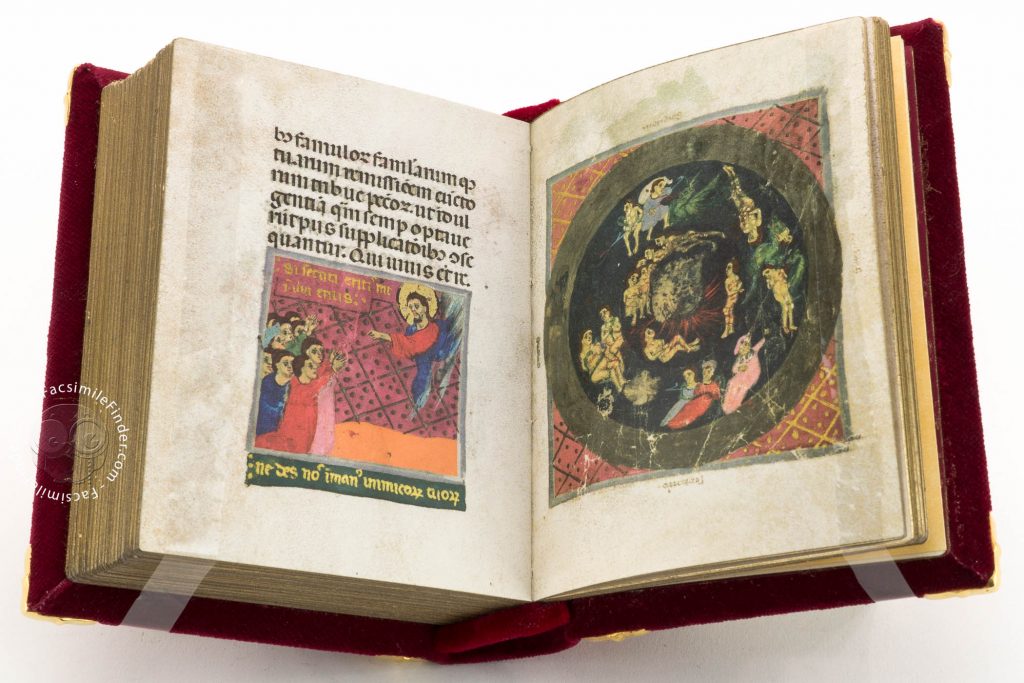

Leafing through the Officiolum we may notice, on several occasions, the influence of the story recounted by the sommo poeta. An example is f. 69r featuring a miniature with the word limbus written on the side. Limbo (literally meaning “margin”, “border”) is the first circle of Hell, Hell’s threshold.

Another instance is f. 156r depicting two circular spaces with concentric strips which, as the Dante lovers may notice, recalls the dantesque structure of the world of the dead, with the different circles following one after the other toward the infernal abyss.

The other important influence is, as previously mentioned, the painter Giotto di Bondone (1270-1337). This one, albeit more difficult to detect, can be identified in particular situations, such as f. 43v where a miniature depicts Joseph sleeping in front of a hut, very much echoing Joachim’s dream in the Scrovegni Chapel.

Giotto’s influence is all the more clear in mass scenes (for example, ff. 56v, 64v, 85r, 112v, etc.) and in the allegorical compositions such as the ages of men (ff. 32v, 44v, 49r, 53r, 57r, 65r) which include: Infantia, Adolescentia, and Pueritia.

All of this information is just a drop in the sea of knowledge and studies developed so far but if you wish to know more, check out the Offiziolo by Francesco da Barberino facsimile edition that comes with a super detailed commentary that might quench your thirst for knowledge! And don’t forget to watch our video.