Our friends from Müller & Schindler surprise us with a new, unprecedented manuscript of the Apocalypse made during a troubled time for Europeans: the beginning of the 15th century.

In the early 1400s, England and France were torn by the Hundred Years’ War, and the Papal Schism of 1378 had spread insecurity and unrest throughout the Christian world. To offer healing or perhaps to portray such feelings, an unknown patron (perhaps Jean, Duke of Berry) commissioned an idiosyncratic illustrated version of the Book of Revelation.

Eighty-five out of eighty-seven large parchment folios feature vigorous, dramatic miniatures which become larger towards the end of the book, allowing viewers to concentrate on the essence of the content. Expressive characters placed against radiant, often complementary colors tell the story of the Book of Revelation in a singular way.

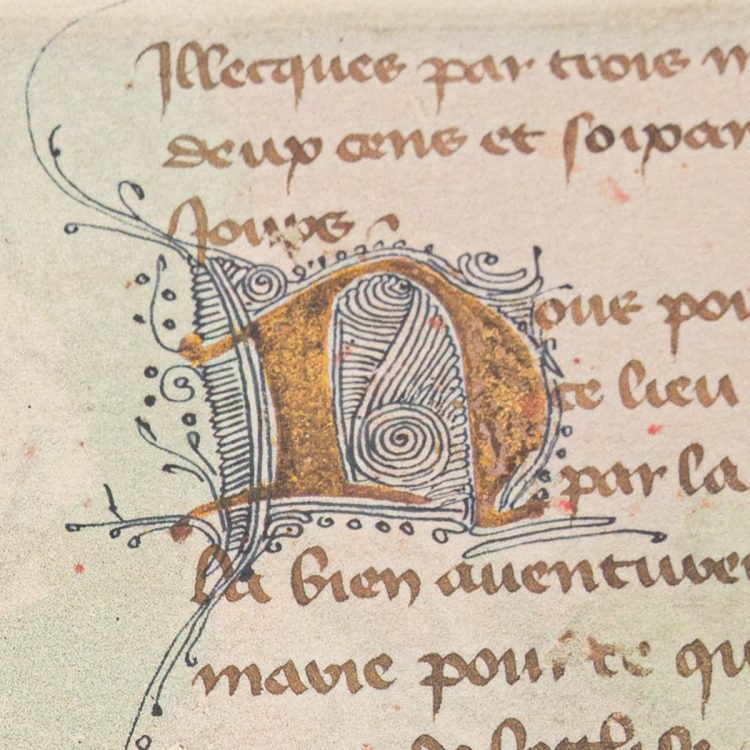

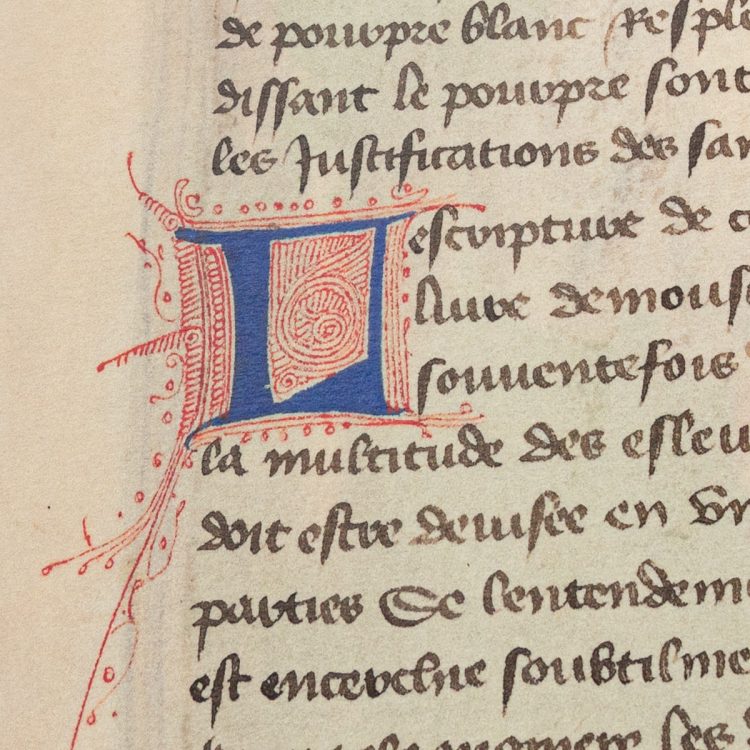

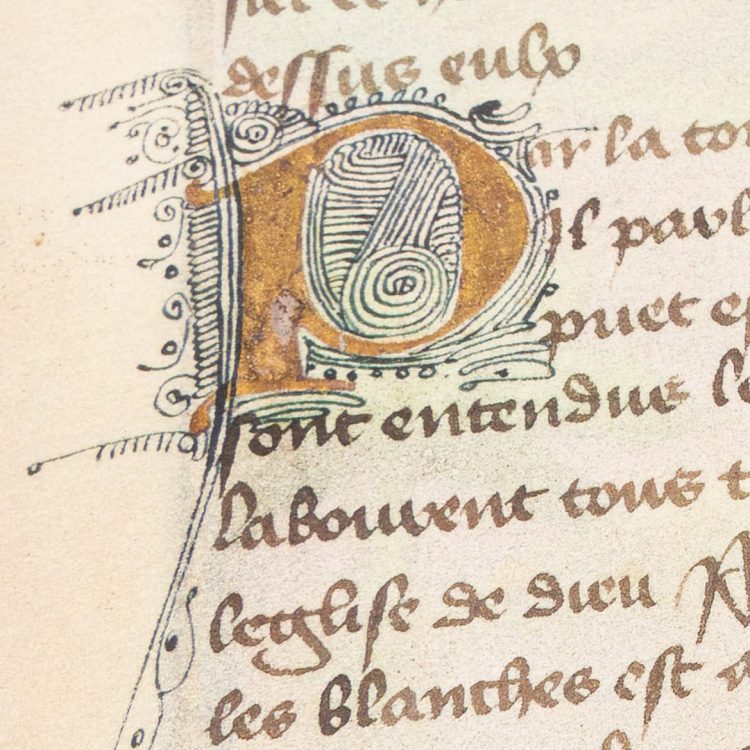

The Middle French text in two columns, penned in Bastarda script, begins below the picture and continues on the right, enriched by rubric captions in Latin and occasional decorated initials. The content of the Book of Revelation is accompanied by a commentary by Benedectine monk Berengaudus.

The Berry Apocalypse suggests that the Church is on the threshold of the Last Days and that prophecies of Antichrist’s persecutions and deceptions are already being fulfilled. – Richard K. Emmerson

The title of this special volume, whose illuminator is also unknown, draws from a partly worn inscription stating Ce livre est au Duc de Berry Jehan. In the early years of the 15th century Jean of Berry, brother of King Charles V, possessed one of the largest book collections of his time, as well as other art objects such as tapestry sets, portraits, jewelry items, medals echoing the ancient Roman tradition, musical instruments, 1500 hunting dogs, and even a monkey.

Although it is hard to assess whether the Duke commissioned the Apocalypse himself, an essay by art historian Richard K. Emmerson points to a religious and political interpretation of the unusually illuminated codex, which symbolizes the tumultuous times its readers were going through.

The pregnant Woman of Revelation on fol. 36v. is in contrast both with other contemporary representations of the Revelation to John and to the New Testament‘s text itself: “a great and wondrous sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.” (Book of Revelation, Chapter 12). The Master of the Berry Apocalypse chose to omit the sun rays that surround the woman according to the biblical text, and to place a particularly large moon under her feet.

According to Emmerson, the moon may be a reference to the Antipope Benedict XIII, whose birth name was Pedro Martínez de Luna. Thus the pregnant Woman of Revelation on fol. 36v., harassed by the Seven-headed Dragon, symbolizes the Avignon papacy tormented by the Roman papacy.

The large, powerful illuminations in the Berry Apocalypse not only provided consolation, stability, and hope to readers during a time of change, but also inspired renowned artists to create their own illustrated version of the Book of Revelation. A few decades after the Berry Apocalypse left its workshop, advancements in printing technology allowed the 27-year old Albrecht Dürer to produce the engravings for his Apocalypse.

The late medieval expansion of the institutional Church and its total absorption into the person of the pope meant that the papal schism was not simply a political argument among rivals but a divisive assault on the spiritual unity of Christianitas. – Richard K. Emmerson

Protected by a dark orange velvet cover with silver clasps, the Berry Apocalypse is currently stored in the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City. Thanks to the ability of facsimile experts from Müller and Schindler, 900 Fine Art facsimiles are now available for purchase with a scientific commentary by Richard K. Emmerson.