Why did Cristoforo de Predis use 15th-century Milan architecture as a backdrop for religious scenes? The answer goes deep into the human mind.

Cristoforo De Predis, born in northern Italy around 1440, was so talented that his illuminations reproduce Renaissance architecture and human emotions down to the smallest detail. He was so versatile that both his devotional manuscript and astrology codex became successful. This essay by Pier Luigi Mulas digs deeper into the illuminations of the Leggendario Sforza-Savoia, unveiling the psychological reasons behind his choice of sceneries.

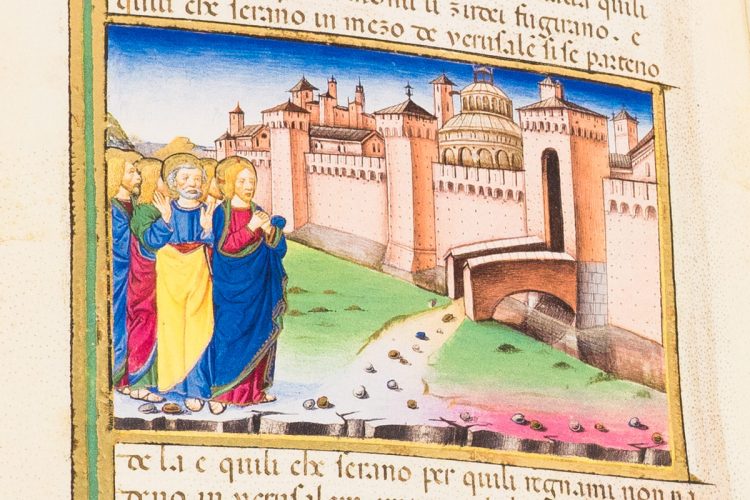

The Leggendario Sforza-Savoia is an instrument of meditation through images. In this sense, the work bears witness to a tradition of devotional practices whereby, while the faithful are called upon to consider the narration of the life of Christ and, above all, the Passion, an appeal is made to the faculties of the imagination and, on a psychological and emotional plane, to intensity of feeling.

The faithful are thus called upon to experience the episodes of the story of Christ and, through the mind’s eye, to see these episodes, through reconstruction, reliant upon imagination, of the settings and characters, which appear, as it were, in a religious performance or imaginary theatre.

Of considerable significance for such devotional practices is the role played by “local memory”, or “memory of loci”. Here, parallels emerge with the processes of the artes memoriae. Through the staging of these episodes of the Gospel in familiar settings, and also through inclusion of figures with which the faithful were already familiar, meditation was facilitated by more instant recall.

The “local” memory, or memory of places, brings the gospel narratives into a contemporary setting so that the reader might impress the sacred narrative upon his or her mind and reconstruct it “imaginatively”.

We find a concrete reference to such practices in one of the most famous contemporary treatises on prayer – the Zardino de oratione* (a text from mid-fifteenth century Venice):

“La quale istoria aciò che tu meglio la possi imprimere ne la mente e che più facilmente ogni acto de essa si reduca ala memoria ti serà utile e bisogno che ti formi ne la mente lochi e persone, chome una citade la quale sia la citade de Hierusalem, pigliando una citade la quale ti sia bene pratica. Nela qual citade ti trovi li lochi principali ne li quali forono exercitati tutti li acti dela Passion.”

(For which story, so that you may impress it upon your mind and so that you may more easily recall each act therein, it shall be fitting and necessary that you form in your mind places and persons as in a city, be it the city of Jerusalem, taking a city that you are most familiar with, in which you find the principal places where all the acts of the Passion took place).

Bearing in mind these premises we can better understand certain iconographic traits in our illuminations: first and foremost, the precise manner in which the urban and domestic settings of the various scenes of the narrative are represented. The streets or thoroughfares, the interiors and the decor evoke the Milan of the times. This is not merely stylistic.

The “local” memory, or memory of places, brings the gospel narratives into a contemporary setting so that the reader might impress the sacred narrative upon his or her mind and reconstruct it “imaginatively”.

Excerpt from an essay by Pier Luigi Mulas, published in the commentary to the facsimile edition of the Leggendario Sforza-Savoia by Franco Cosimo Panini Editore.

*According to the Zardino de Oratione, an essay published in Venice in 1453, meditation takes place thanks to “mental images” that make the sacred scene come alive to readers.