This is the story of how I got to lay my hands on the original leaves of the Psalter of Blanche of Castile. I knew that the manuscript Müller & Schindler is planning to publish in facsimile is a piece of world history, but I wasn’t expecting such a holy experience.

My short but intense visit to Paris began on Tuesday night, when Charlotte Kramer from Müller & Schindler, art historian Eberhard König, Giacomo Cecchetti from Pazzini Stampatore and I had crêpes and cider at a traditional French bistrot. I needn’t say we were quite sleepy after such a “light” dinner!

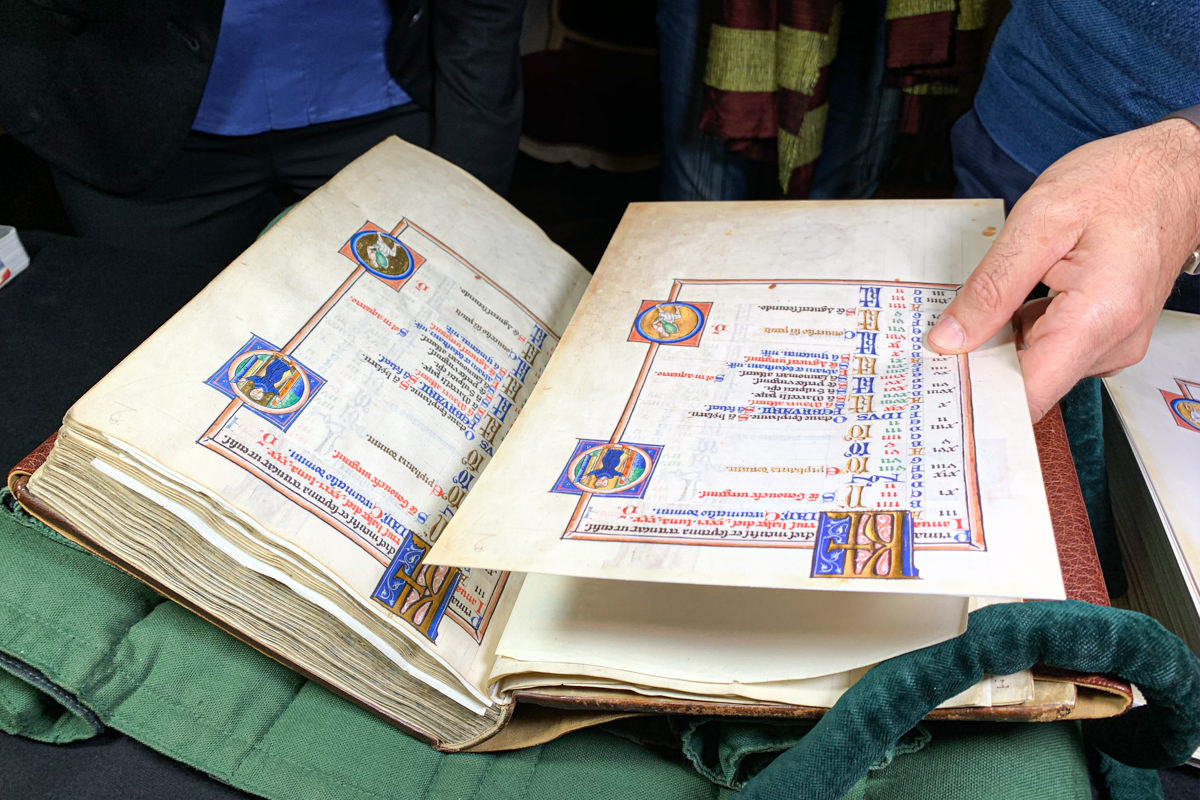

Early the next day, a foggy morning walk along the Seine led us to the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, a section of the French national library boasting over one million historical books, prints, music sheets, and manuscripts. In the 18th century, this imposing institution obtained one of the most exquisite examples of Parisian Gothic illumination: the Psalter of Blanche of Castile, which we had come to color proof and analyze with a view to creating a new facsimile edition.

Before we even took off our coats, two of the library’s curators asked us who were the “chosen ones” who would be touching the cherished volume. As soon as we shyly raised our hands we were kindly led to the nearest toilet to carefully wash our hands – no questions asked.

A curator stayed with us for the whole color proofing session, never taking their eyes off the manuscript and following our every move. I had barely opened my mouth to ask the reason for such concern, when they told us that the French consider this particular psalter a relic of St. Louis. “It’s the same as touching Jesus’ finger!” She couldn’t have made it clearer.

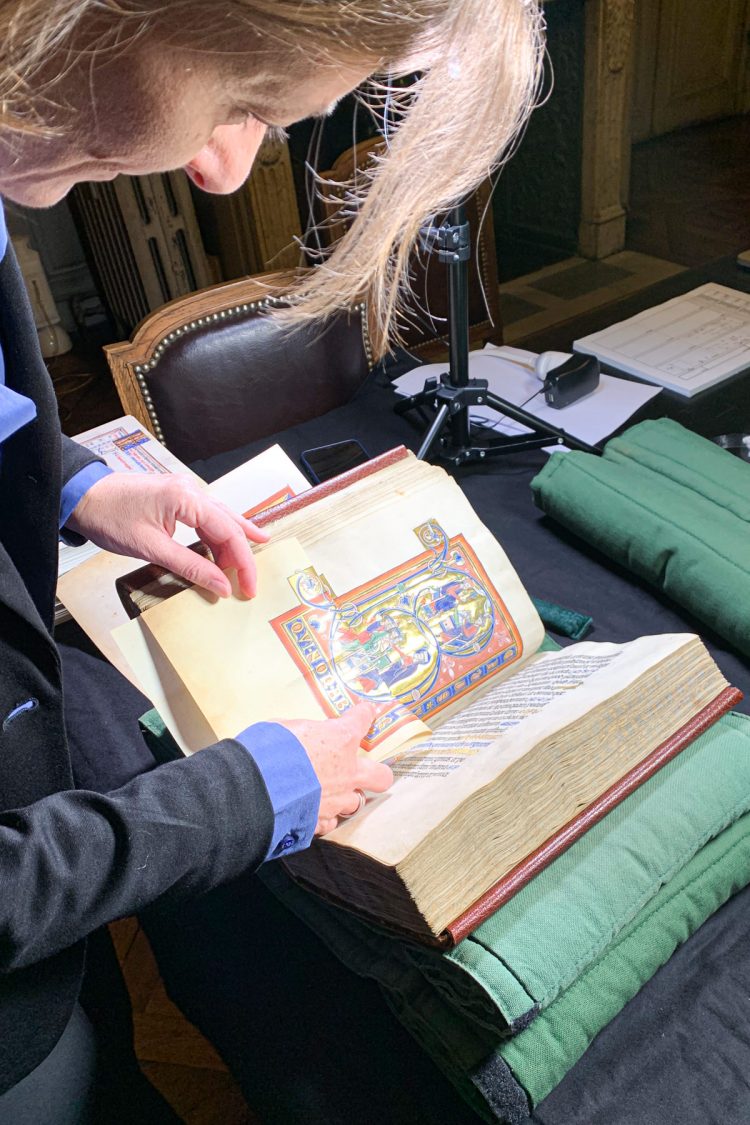

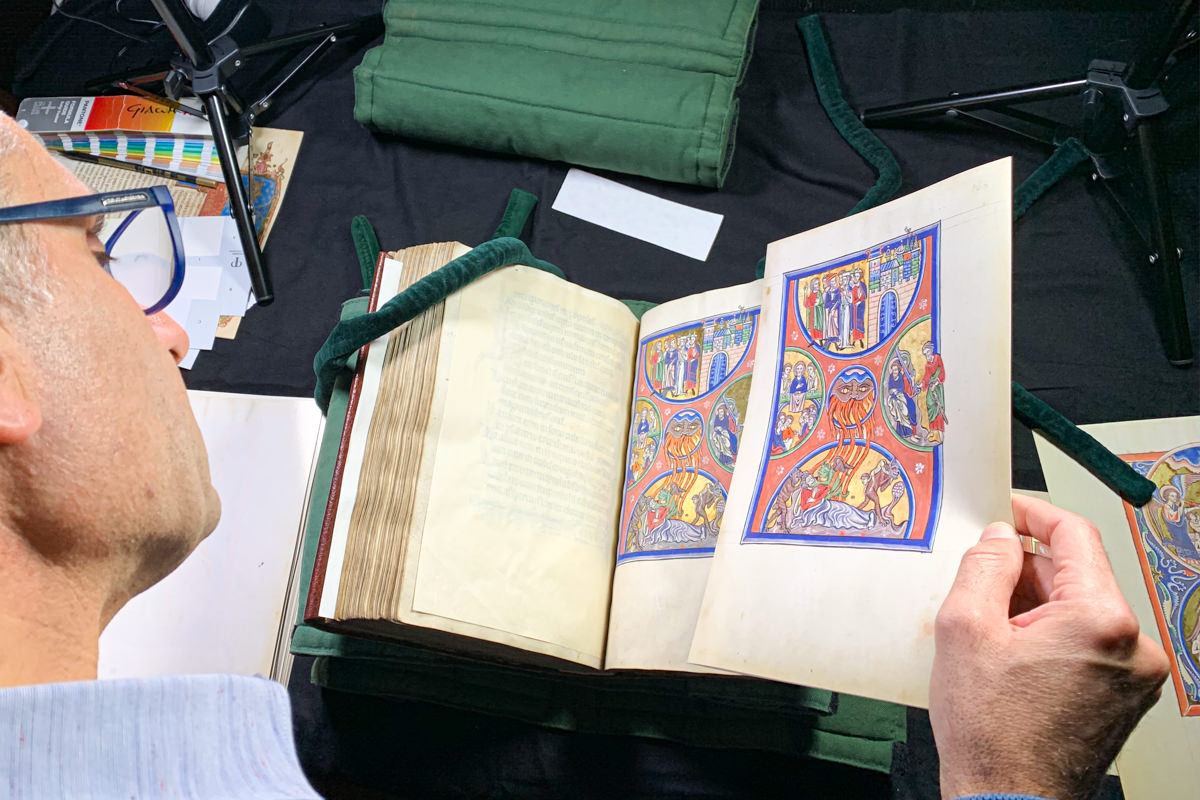

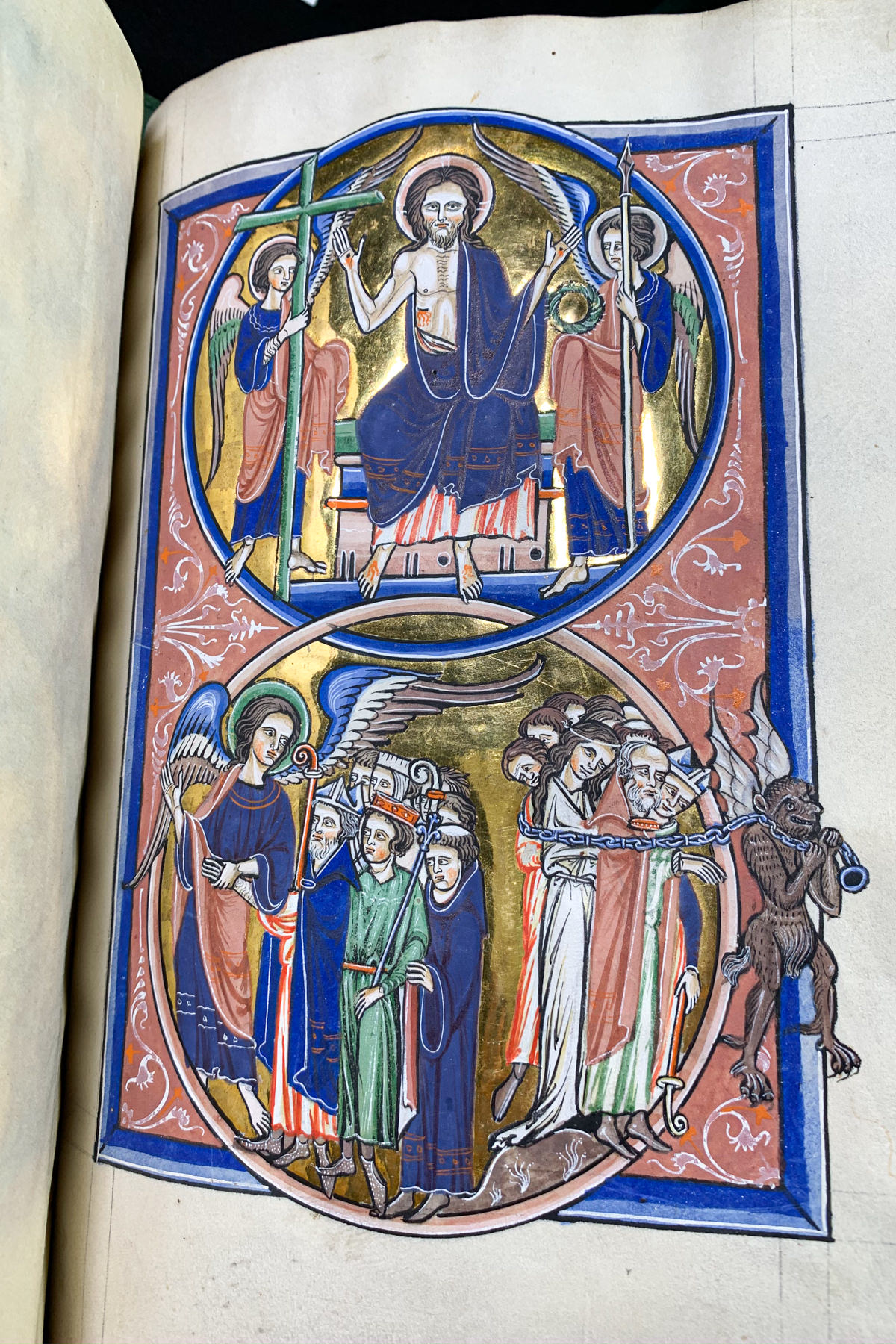

But when the first folio of the Psalter was laid before us and the light reflected by the century-old-gold leaf lit up the room, all questions suddenly seemed pointless. The thick codex, as though illuminated from within, looked as if it had been taken to the Parisian library by a time-machine – almost nothing about it seemed to have aged since its creation in the first decades of the 13th century. As a flabbergasted Charlotte and a speechless Eberhard König moved closer to the cushion on which the Psalter lay fully open, I wondered in silence whether they shared my thoughts.

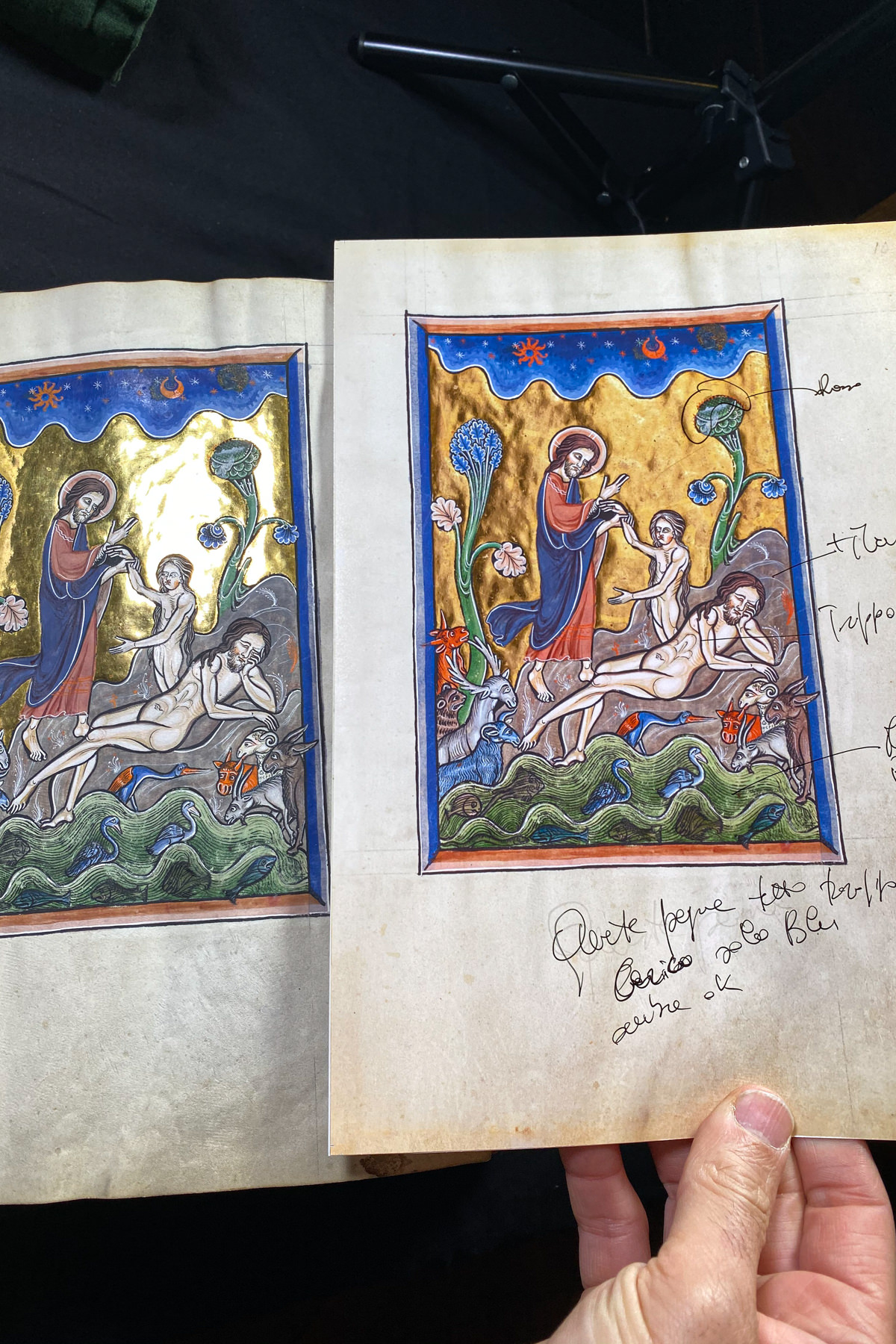

Ten years in the facsimile industry have taught me that digitization, although exceptional, never succeeds in conveying every detail, as a certain amount of information is always lost when the image passes from the folio to a computer. Because gold leaf reflects light, the outcome of digitization depends on the angle at which the rays of light hit the illuminated area.

I would have never imagined seeing a perfectly smooth gold surface survive on the parchment of an eight-century-old book, yet here it was before my eyes! Another common trait in ancient manuscripts are the silver-decorated portions which often turn black due to oxidation, but when I looked into the devil’s eyes I noticed that they shone in every direction, revealing perfectly preserved silver (and a subtle shiver ran down my spine).

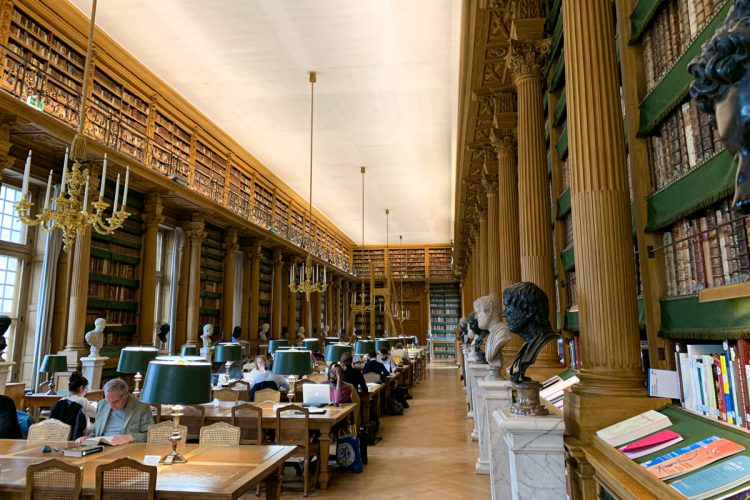

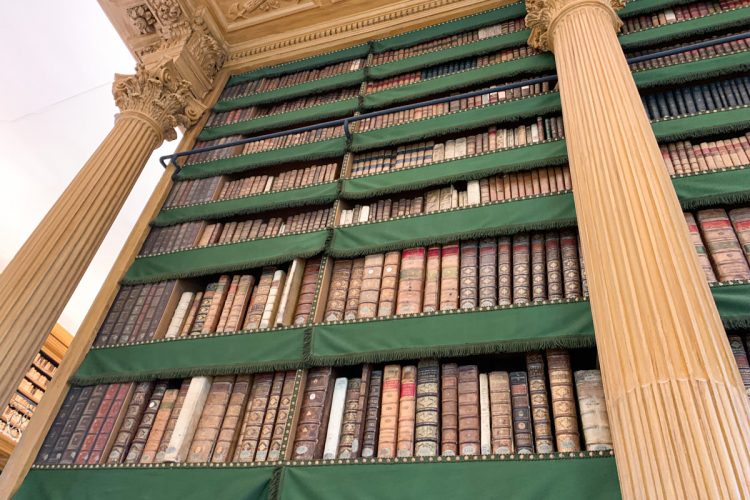

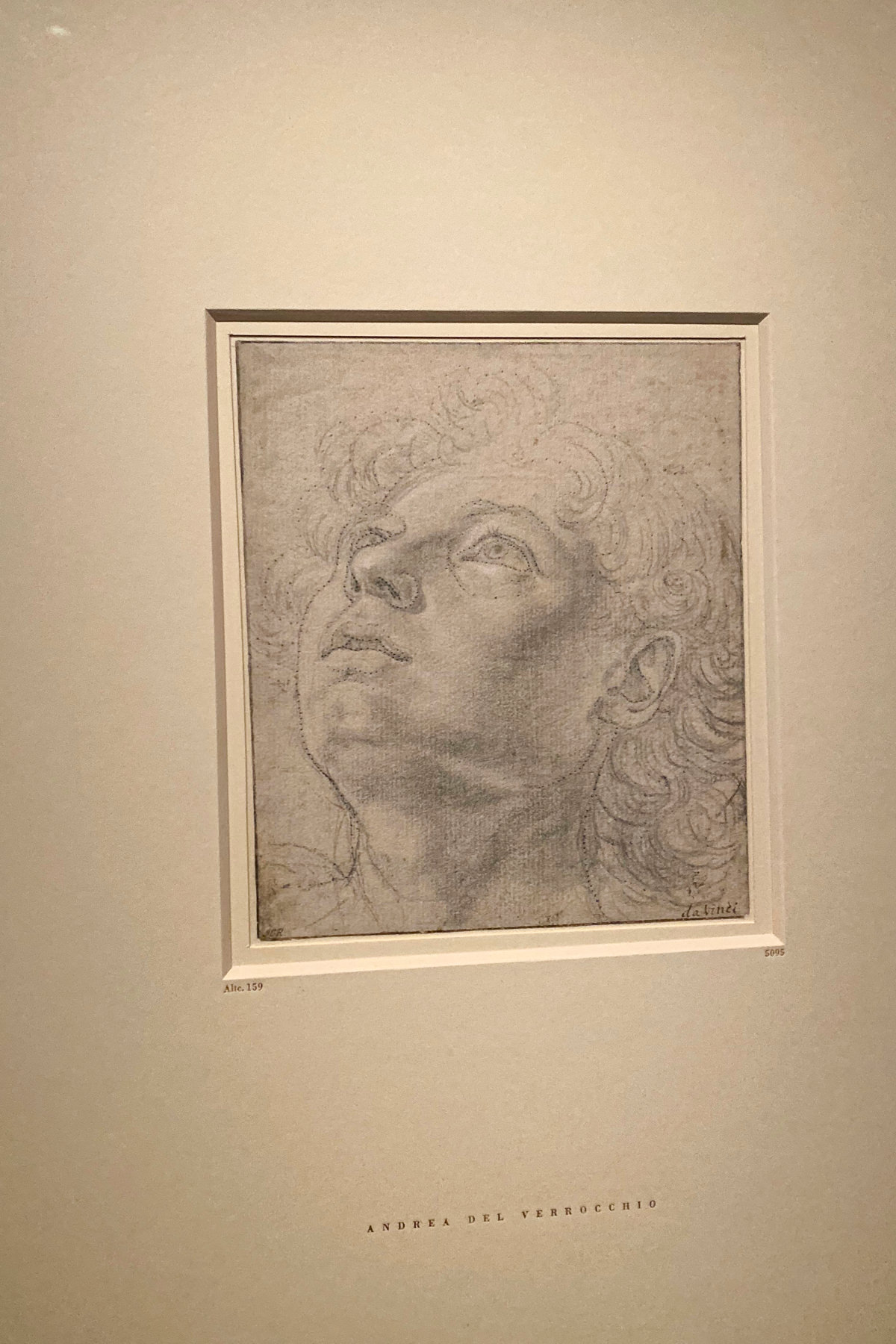

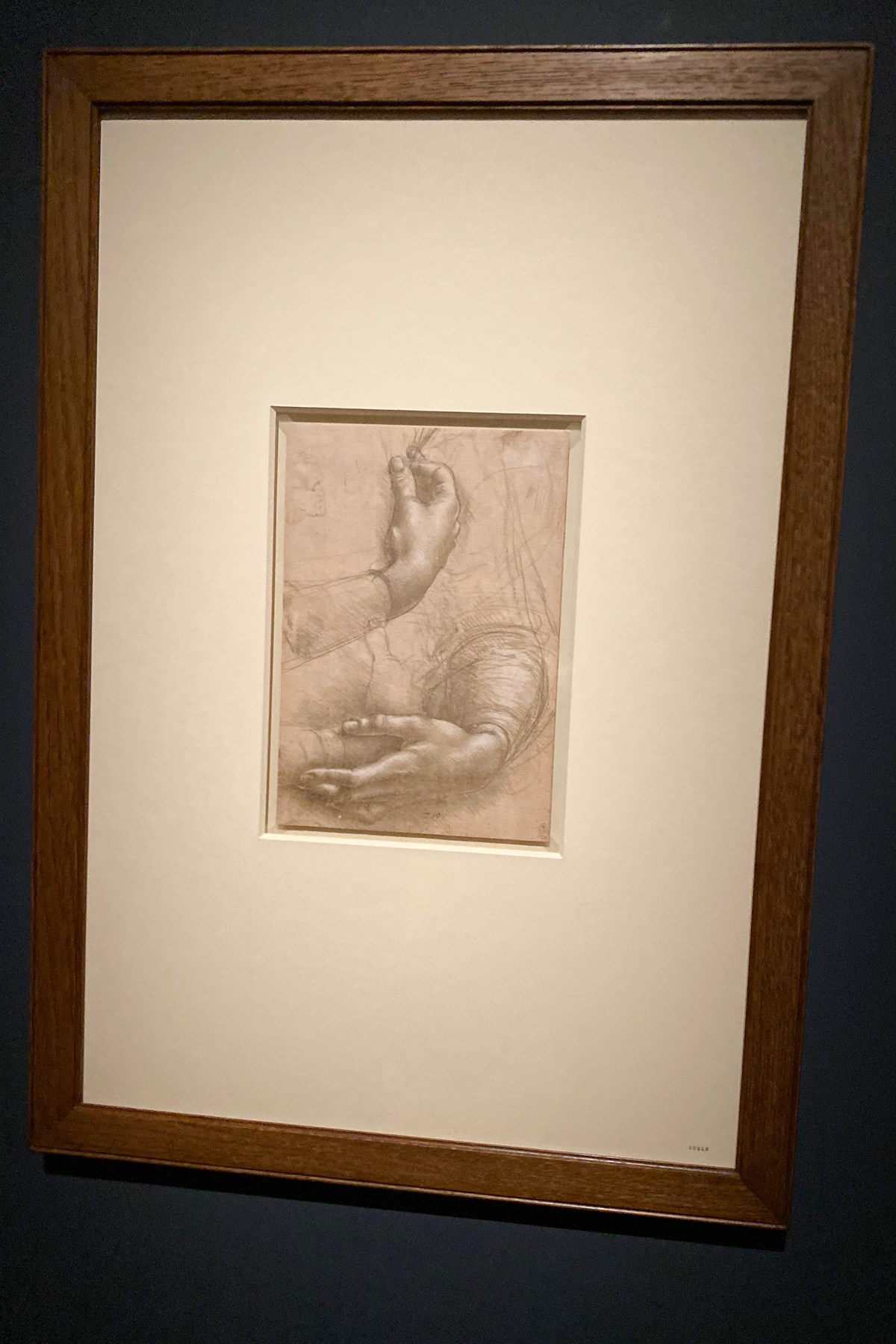

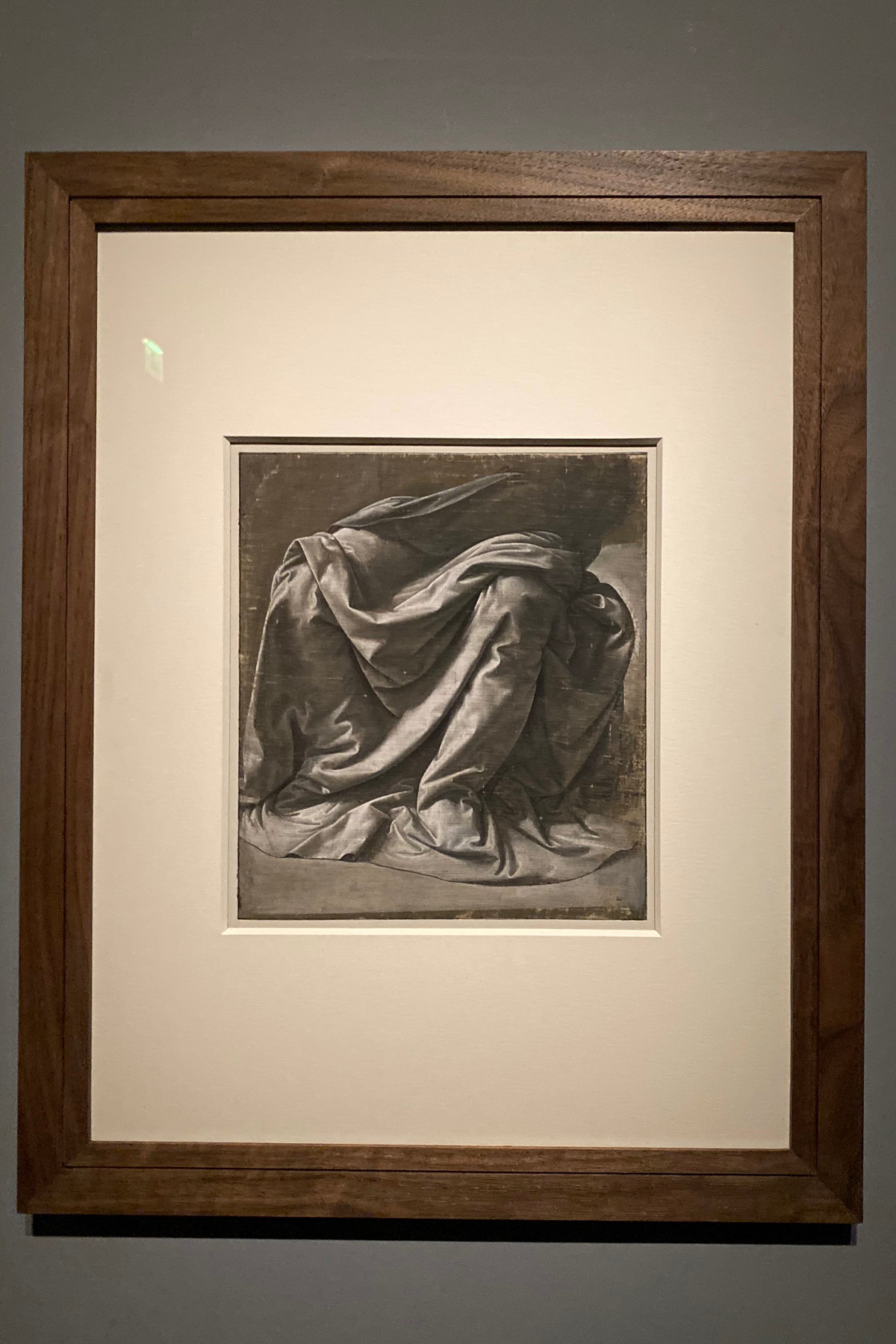

As the clock struck twelve, the three of us raced down the marble staircase, across the street in front of Nôtre Dame, and into the glass pyramid of the Louvre where a superstar history guide, Eberhard König, led us through the preview exhibition on Leonardo da Vinci – we barely had time to stop by at the fabulous Mazarin Library to admire its ancient book collection and wood engravings.

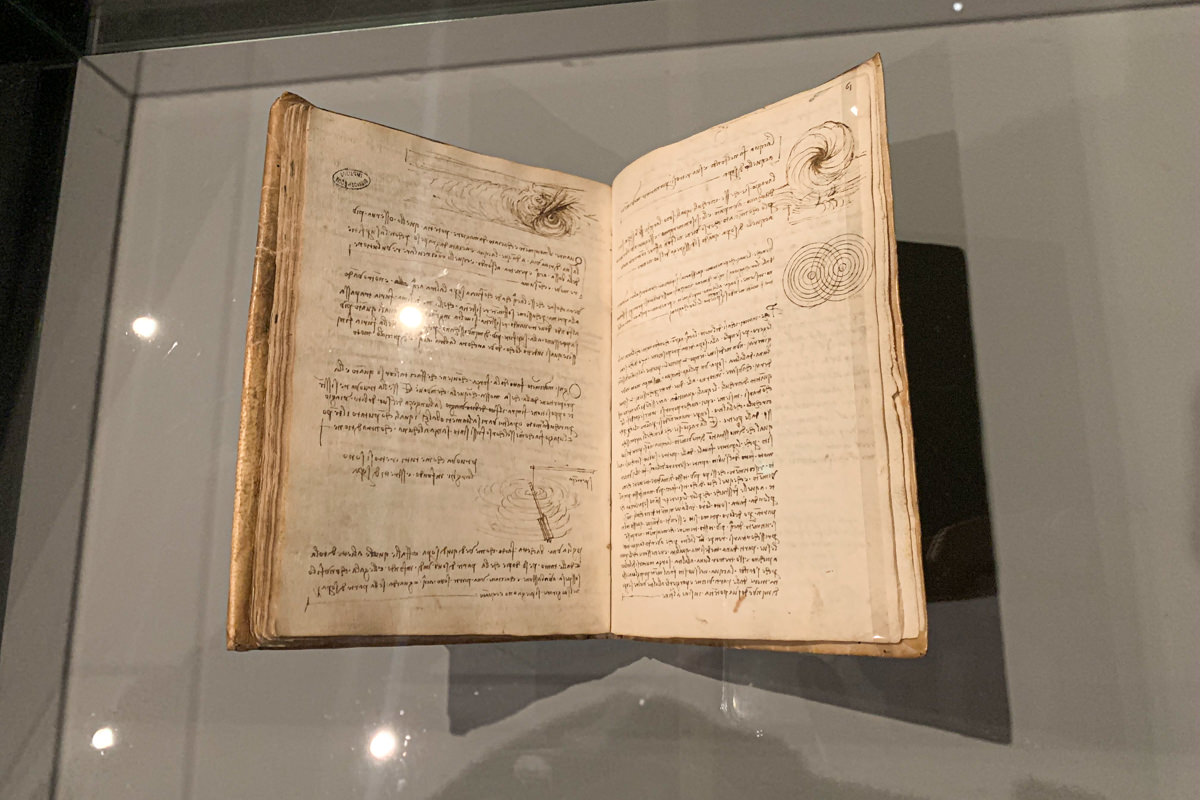

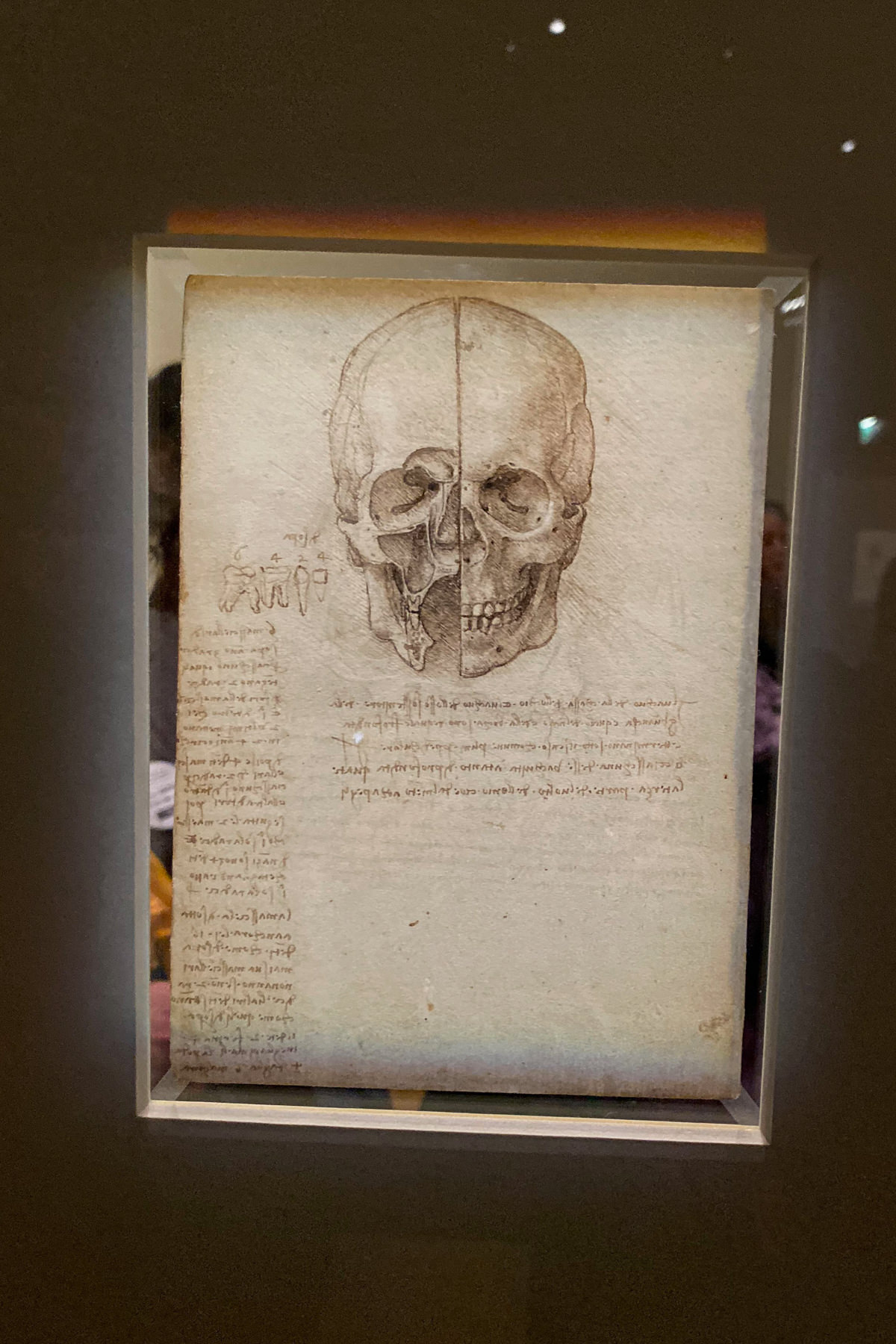

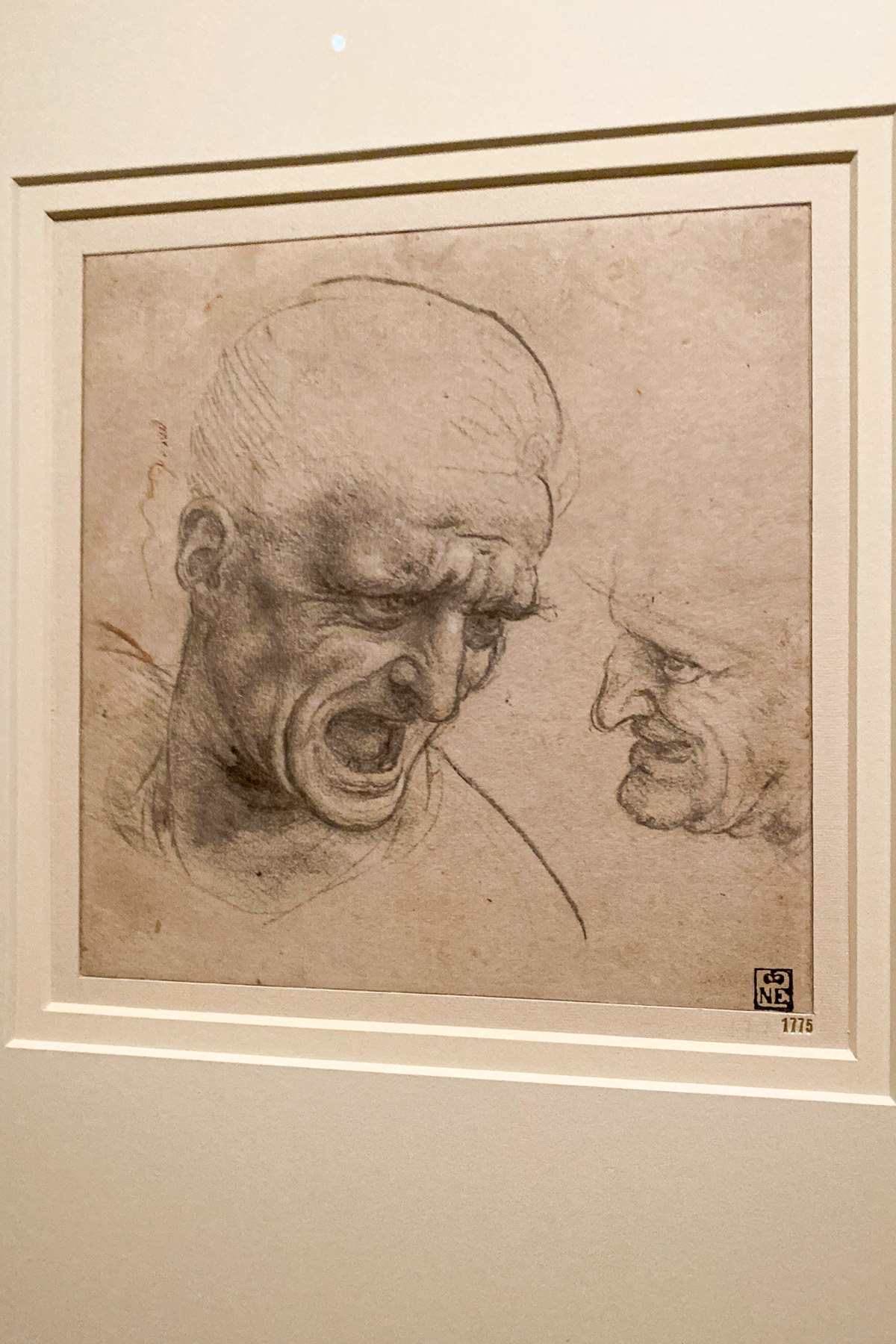

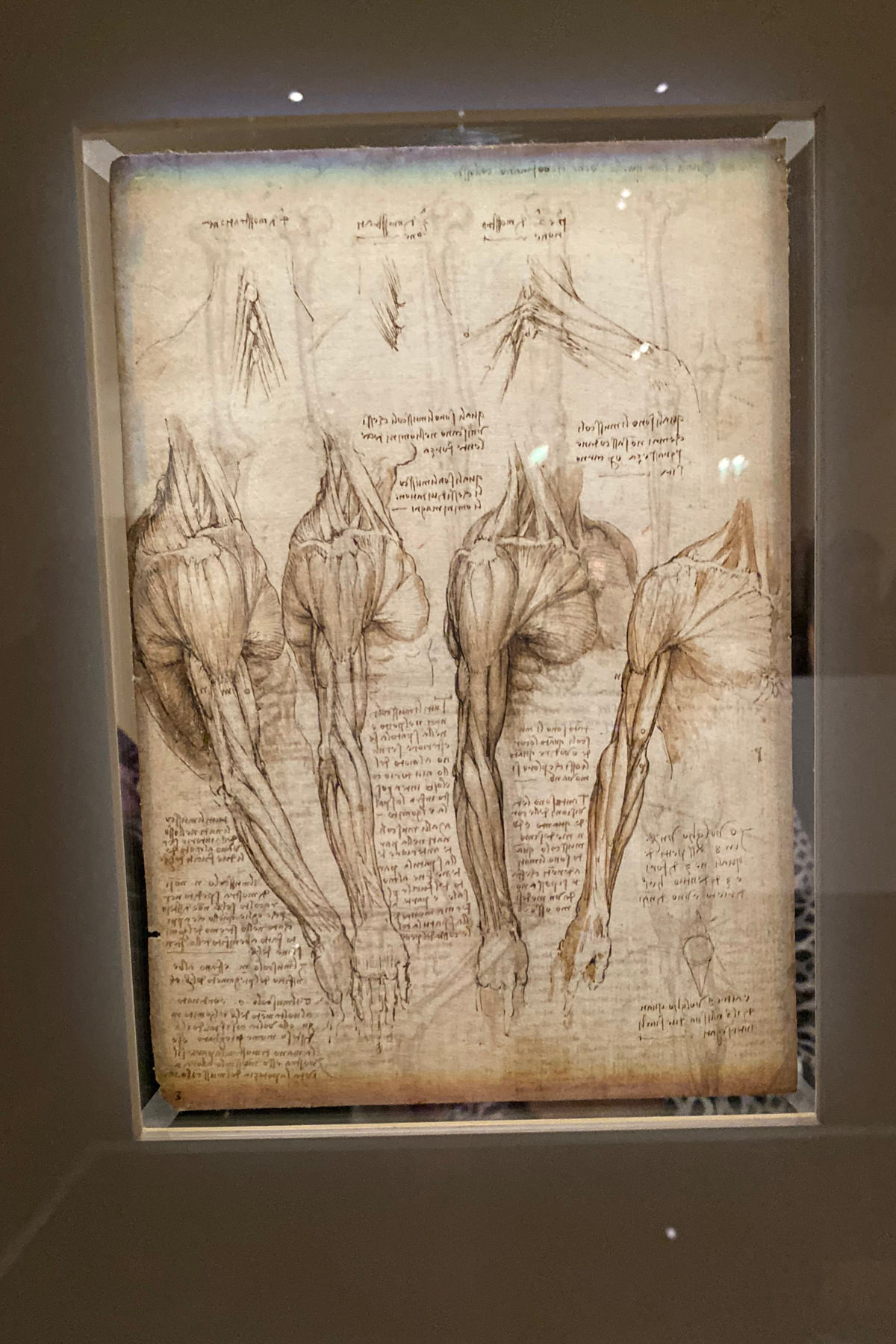

It was a pleasure and a privilege to listen to Eberhard König, a renowned manuscript expert, point out the differences between Leonardo da Vinci and other contemporary artists. Thanks to him, Charlotte and I learned that the Renaissance genius had the habit of painting nude figures first and dress them with clothes at a later stage. However, Charlotte and I could not stop thinking of a particular group of sketchbooks we will hold in our hands in just a few months: twelve booklets on science and technology Müller & Schindler is preparing to produce in facsimile to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death.

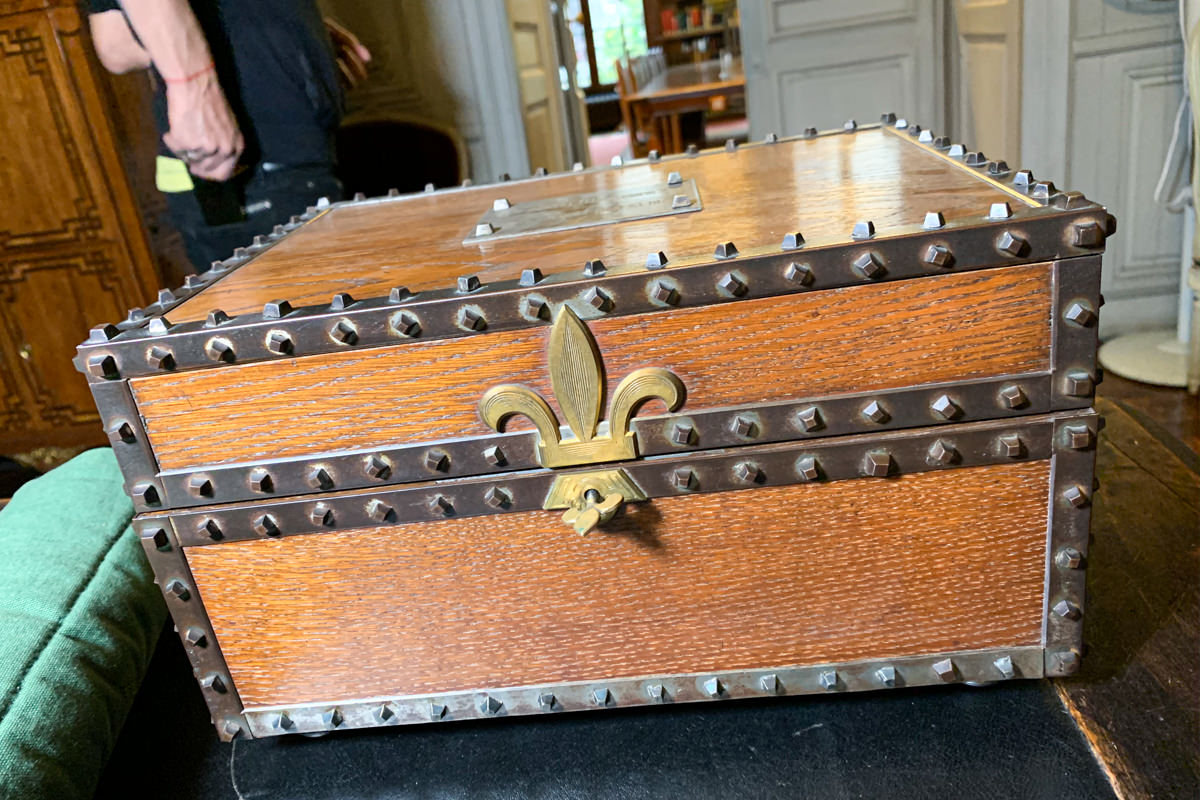

After just a couple of hours, with our eyes full of beauty, we returned to the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal to color-proof the remaining miniatures, analyze further details and measure both the holy manuscript and its 19th-century wooden case.

We consider ourselves proud and satisfied with the information we have gathered and for the fact that we, out of all people, had the honor of seeing the world-famous marvel with our very eyes. Guess what we had for dinner? Onion soup! But this time we ordered three glasses of Kir Royale – crème de cassis topped with champagne – to celebrate our special day and wish ourselves luck for the following months. An ambitious task lies before us: after six weeks of hard work on the digital files, and after printing a new, perfected version of each folio, we will meet again in Paris to decide on how to forge the precious facsimile of the Psalter of Blanche of Castile.

A huge thanks to Charlotte Kramer for giving us this unique opportunity to admire such a treasure; and our eternal gratitude to the library’s officials, Louisa Torres and Khadiga Aglan – none of this would have been possible without their endless patience.