Early illuminated manuscripts of the Divine Comedy exhibit a diverse array of formats. In this article, art historian Elizabeth C. Teviotdale presents five notable examples from the fourteenth century to illustrate the various methodologies employed by book artists in their interpretations of the poem.

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) composed his masterwork, eventually named the Divine Comedy, when he was exiled from his native Florence in the early fourteenth century. The Commedia is a long Christian moralizing poem that chronicles Dante’s observations of the condition of the damned and saved over the course of a one-week journey through the world of the dead.

Immediately Read and Interpreted

The poem comprises three cantiche (canticles), 100 canti (songs), and 14,233 lines of verse. It is self-consciously epic in proportion and treats the theme of the human soul’s quest for a clear understanding of the love of God in a confused and confusing world. Written in the Italian vernacular, it was immediately read and revered.

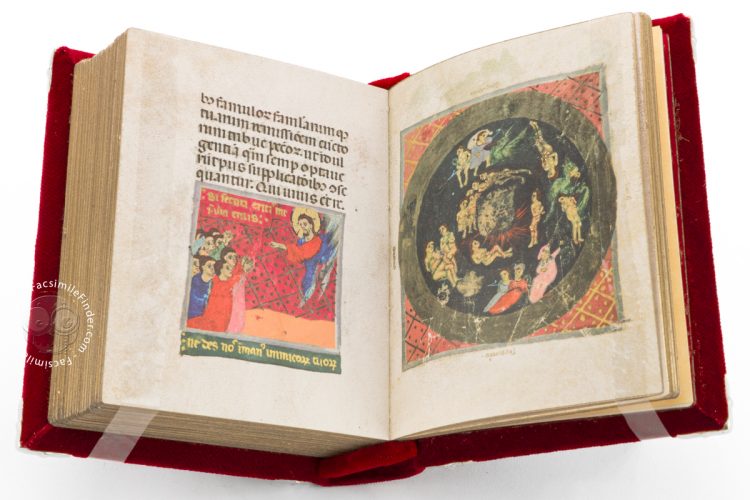

It has been speculated that the poem’s description of hell influenced miniatures in the Officiolum of Francesco da Barberino, probably made in the first decade of the fourteenth century.

Dante is both the protagonist and the narrator, and he encounters characters from history (often recent), myth, and the Bible. The dizzying array of allusions to ancient literature and contemporary politics immediately attracted commentary in epitomized guides and glosses on individual episodes.

Illuminating the Poem

Early illuminated manuscripts of the Commedia take a variety of formats. We feature here five examples from the trecento (fourteenth century) to give a sense of the approaches to the poem taken by book artists working within a few generations of the poet’s death.

Historiated Initials

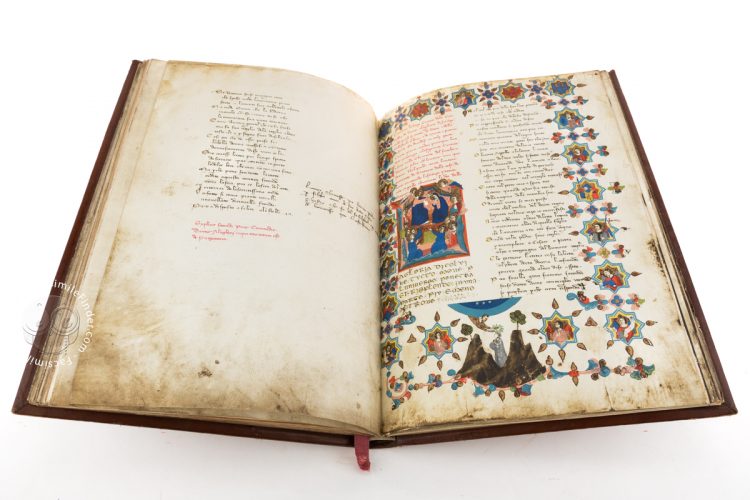

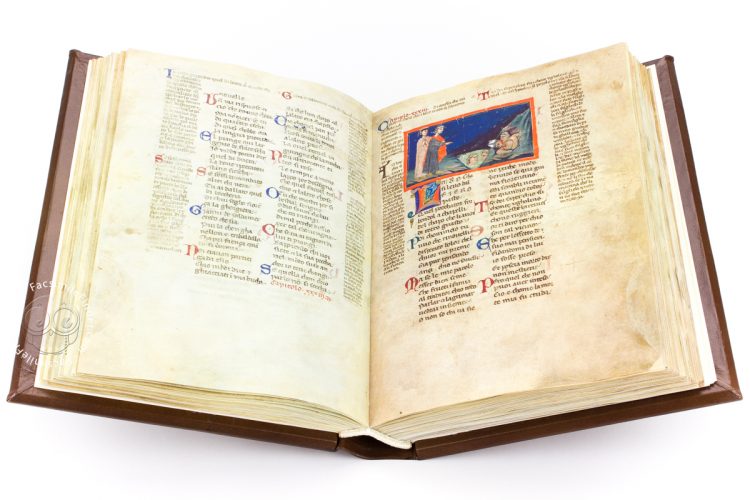

The most common form of illumination among the early manuscripts is to mark the beginning of each of the three canticles with a historiated initial (a painted initial that contains identifiable figures). In the Trivulziano 1080 Manuscript, the poem is written in two columns in an elegant cursive script, and the opening of each canticle features a historiated initial and border decoration with a scene or scenes illustrating the poem in the lower margin.

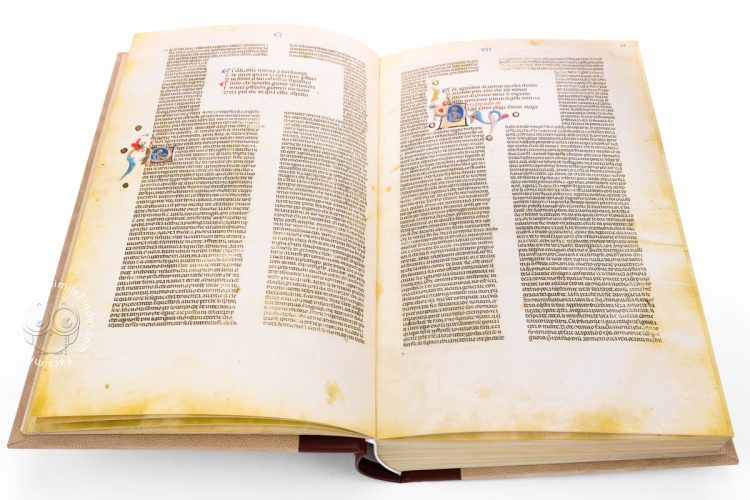

In the Florence-Milan Manuscript, the poem is written in a single central column surrounded by commentary. A historiated initial marks the opening of each canto of the poem and its commentary.

Bas-de-Page Scenes

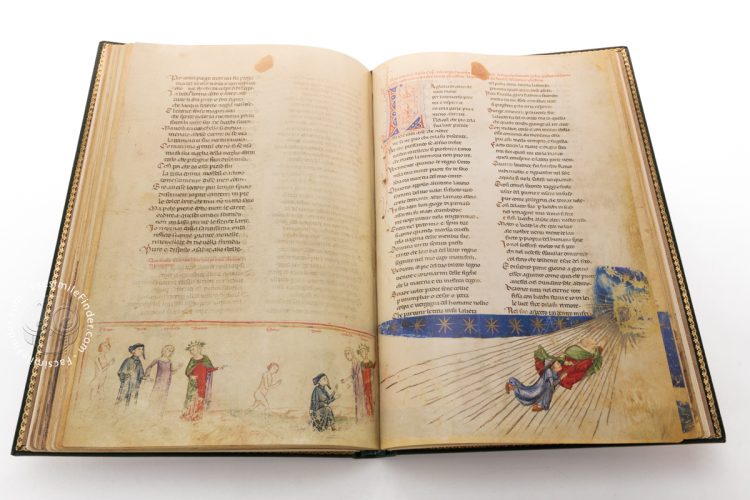

Another approach to illuminating Dante’s poem is to illustrate the poem’s episodes in bas-de-page scenes (paintings in the lower margins of text pages). These are often unframed or only partially framed, as in the Holkham Manuscript, where the scenes often extend up into the inner or outer margin or the space between the two columns of text.

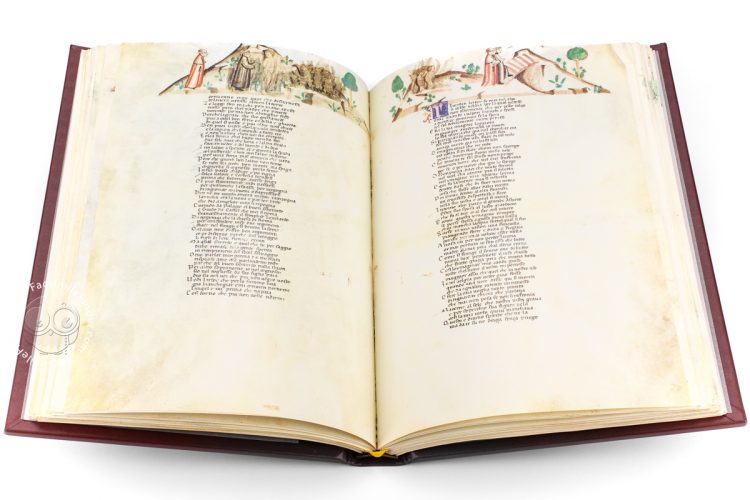

Continuous Illumination on the Upper Margin

A very unusual approach is found in the Estense Manuscript, where every page of the poem’s text—written in long lines (a single column)—has an illustration in the upper margin. The generous inner, outer, and lower margins of this book contrast sharply with the visual activity at the top of each page, and it is possible that the inclusion of illumination was not a part of the original plan.

In-Text Miniatures

In the Palat. 313 Manuscript, the poem occupies two narrow columns—so narrow that a single line of verse often requires two or three lines of writing—surrounded by glosses. Most of the miniatures appear “in text” (not in a predictable area of the page) and extend over the two columns of the main text. Others are restricted to one column of the poetic text, sometimes extending into the inner or outer margin. In many manuscripts featuring in-text miniatures, a historiated initial also introduces each canticle.

Picturing Hell

Inferno is the portion of the Commedia for which we have the greatest quantity of surviving illumination. This is both because this portion of the poem is visually evocative and because it is the first of the poem’s three canticles—Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso—and thus, in some instances, was the only portion where the painting was completed.

The Visualization of Dante’s Inferno in Early Manuscripts

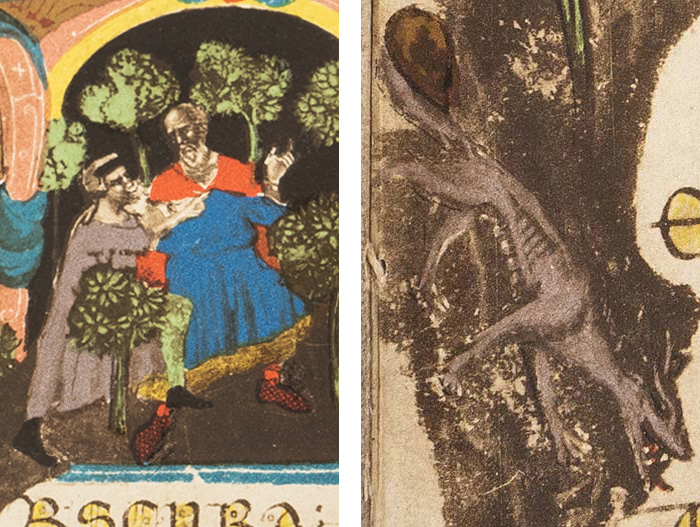

Trivulziano 1080 Manuscript, fol. 1r (Canto 1)

Dante, in a mauve-colored robe, has been lost in a “dark wood.” He tried to escape, but wild beasts (including the wolf pictured in the margin below the initial) chased him back in. The ancient Roman poet Virgil (70-19 BCE) is pictured leading the author out of the wood and up a mountain to begin his journey

Florence-Milan Manuscript, fol. 16r (Florence) (Canto 7)

The damned soul of a miser clutches a money bag and cries out in anguish, or Plutus—the god of wealth in ancient mythology—invokes Satan.

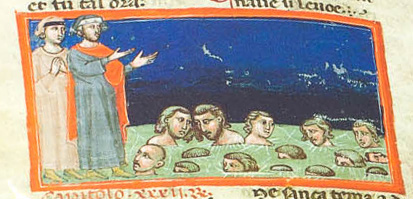

Palat. 313 Manuscript, fol. 74v (Canto 32)

Dante and Virgil stand on the frozen lake where traitors of their kindred are trapped. Among them are the brothers Alessandro and Napoleone degli Alberti butting heads. They killed each other over their inheritance and politics in the 1280s.

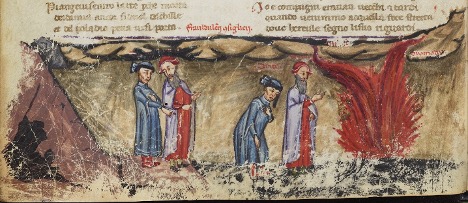

Holkham Manuscript, p. 40 (Canto 26)

Virgil addresses the legendary ancient king Ulysses, who appears in a flame. The king tells his story, and Dante (in blue) reacts.

Estense Manuscript, fol. 38r (Canto 28)

Virgil and Dante witness the torment of the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad (d. 632), and other “sowers of discord.” They have had their entrails exposed and walk around a “road of pain” represented as a green lake. The devil bearing a sword will renew their wounds each time they encircle the lake.

Illuminated Manuscripts of the Commedia

This partial list includes only manuscripts that have been treated in facsimile editions.

Codices with Historiated Initials (and No Independent Miniatures)

| Manuscript | Date | Origin |

| Trivulziano 1080 | 1337 | Florence |

| Florence-Milan | 2nd quarter of the 14th century | Veneto |

| Frankfurt | after 1350 | Northeast Italy |

| Padua 9 | 2nd half of the 14th century | Italy |

Codices with Bas-de-Page Miniatures

| Manuscript | Date | Origin |

| Strozzi | 2nd quarter of the 14th century | Florence |

| Holkham | 3rd quarter of the 14th century | Italy |

| Add. 19587 | ca. 1370 | Naples |

| Pluteo 40.7 | ca. 1380-1390 and 15th century | Florence (?) |

| Yates Thompson | early 15th century | Siena |

Codices with In-Text Miniatures

| Manuscript | Date | Origin |

| Palat. 313 (= Poggiali) | 2nd quarter of the 14th century | Florence |

| Egerton | ca. 1340 | Bologna or Padua |

| Budapest | mid-14th century | Venice |

| Oratoriana | ca. 1355-1360 | South Italy |

| Padua 67 | 2nd half of the 14th century | Italy |

| Hamburg-Altona | ca. 1350-1410 | Tuscany |

| Marciana | last quarter of the 14th century | Veneto |

| Gambalunga | late 14th century | Padua |

| Angelica | 14th century | Bologna |

| Guarneriana | early 15th century | Florence (?) |

| Paris-Imola Inferno | 1430-1450 | Milan |

| Urbinate | ca. 1477-1482 | Urbino |

Other Formats

| Manuscript | Date | Origin | Format |

| Estense | ca. 1380-1390 | Italy | Unframed miniatures at the tops of pages |

| Banco Rari 215 | 1410-1450 | Florence | Portrait and full-page miniatures |

| Divine Comedy by Sandro Botticelli | 1482-1490 | Florence | Drawings |

| Dante Historiato by Federico Zuccaro | ca. 1586-1588 | Spain | Drawings |

ONLINE RESOURCE:

Illuminated Dante Project. A project that aims to provide a systematic survey and an accurate description of early illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy, identifying references to the poem and its commentaries.