In April 2021, Giovanni was invited as a guest speaker at Harvard University. Read through his own report on the talk he gave on the production of manuscript facsimiles and their use for teaching, research, and artistic purposes.

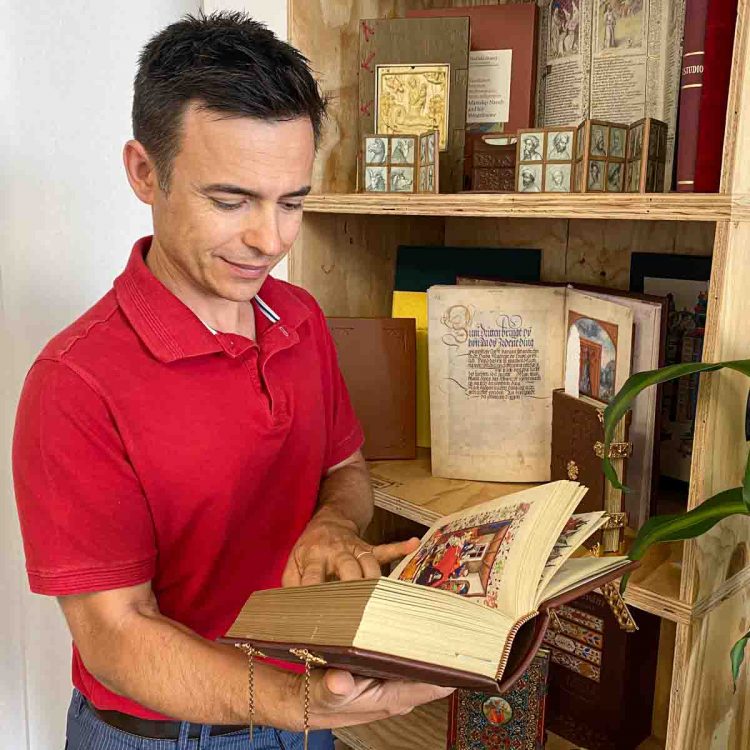

As the founder and owner of Facsimile Finder, part of my job carries with it an aspect of divulgation about the fascinating world of ancient manuscripts and their facsimile editions, and that’s something I commit to with enthusiasm and passion.

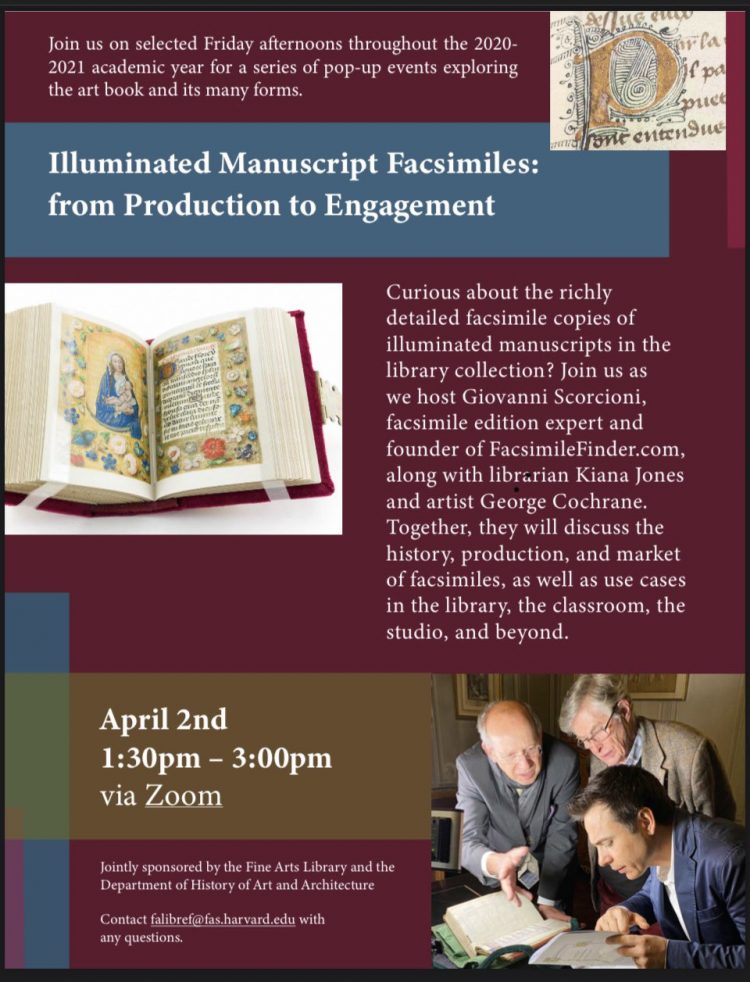

That’s why I was beyond honored when, in April 2021, I got an invitation from the Herman and Joan Suit Librarian, Shalimar Fojas White, and Research & Collections Librarian Jessica Evans-Brady to speak about facsimiles of illuminated manuscripts at Harvard University in a series of pop-up events exploring the art book.

In my talk, I discussed the history, production, and market of facsimiles, as well as use cases in the library, the classroom, the studio, and beyond. The event was attended by around 70 folks from the Harvard community, and jointly sponsored by the Harvard Fine Arts Library and the Department of History of Art and Architecture.

I began by recounting how I first got started in the luxury bookselling industry more than 13 years ago. With no background in the field and coming from a short career as a professional double bass player, there was so much to learn!

From the very beginning I knew that I wanted to do something different from the mainstream facsimile market, which was mostly made of wealthy private collectors.

By sheer coincidence, a few months later my wife Giulia was witness to a conversation a few scholars had from an important American institution, who mentioned that they often used facsimiles for research and teaching. This struck Giulia to the point that she reported the conversation to me, suggesting that perhaps we should learn more about the scholars’ needs in regards to manuscripts and facsimiles.

After many conversations with faculty and art librarians, the concept of the Facsimile Finder website came into our minds, and the final version of the website that you see now slowly came into being. FacsimileFinder.com is an online catalog that strives to present, in an attractive yet scholarly fashion, all existing quality facsimiles produced from the 1950s to the present. Today, the site contains over 1,900 records, and is the first and most comprehensive online catalog of facsimiles that serves libraries, scholars, and collectors all over the world.

As I learned more about the needs of scholars and librarians, I also learned much in terms of the market and production of deluxe facsimiles.

The Market

- The market for facsimiles began to take shape in Europe in the 1960s and 70s.

- A few selected publishers, mostly located in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, started to focus on facsimile production, with an initial market share of 90% of sales to libraries, and 10% to private collectors. Since then, there’s been quite a switch, and today less than 1-2% of the facsimiles go to libraries, while the rest is absorbed by private collectors.

- Starting in the 1980s, the market expanded beyond Germany to Spain and Italy. Today, these are still the three main areas of Europe where most facsimiles are sold.

Production of Deluxe Facsimiles

Facsimile production includes five steps:

- Choice of the manuscript and planning

- Photography

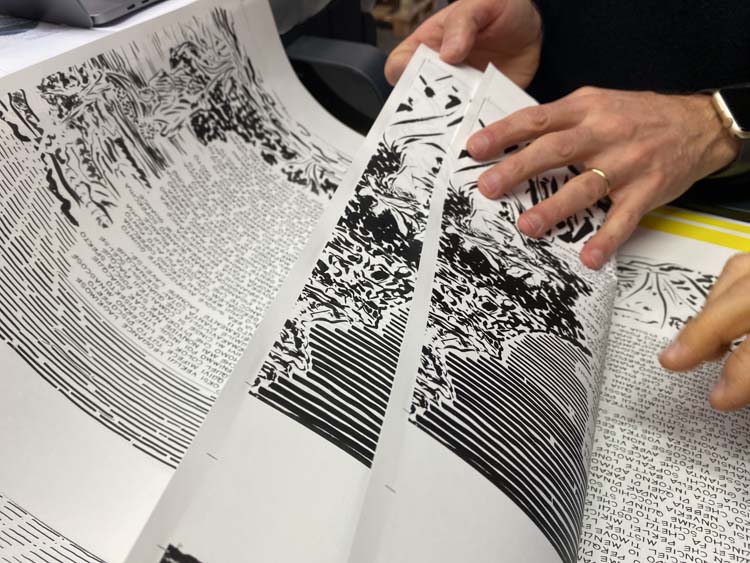

- Digital Editing known in the industry as Pre-press

- Printing

- Binding

A Careful Manuscript Choice is Essential

The first step in the production of a facsimile is the choice of the manuscript, and most publishers stick to a fairly strict formula while making this choice. To quote Gunter Tampe, one of the founders of Quaternio Verlag Luzern and an expert in the field of facsimile production:

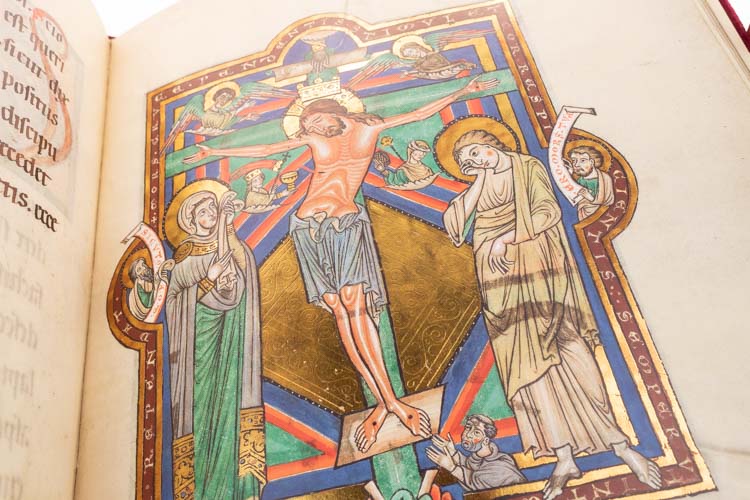

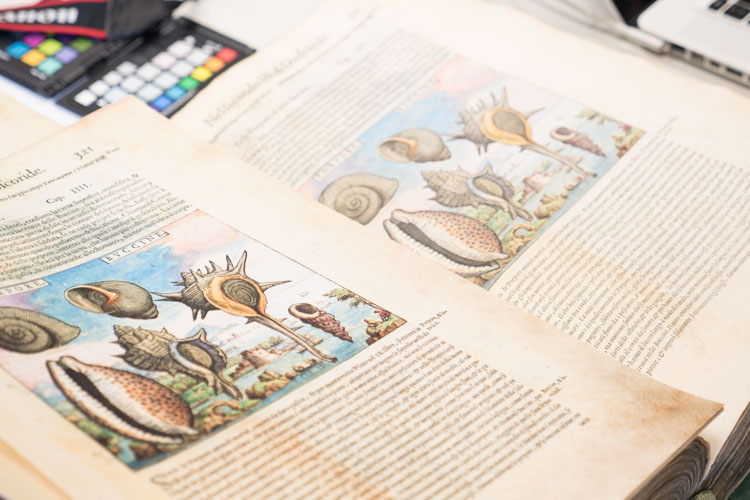

The manuscript must have high-quality paintings. It might not be enough to have drawings by famous artists: we could reproduce the work of an artist who is not very well known, but who stands apart in his area. It is better to have manuscripts with lots of miniatures: contrary to popular belief, having much text but not a lot of illuminations doesn’t make the facsimile much cheaper. The gold is always a bonus, because it gives value to the collection of private customers and, when applied properly, it’s a pleasure for the eye; so, the more illuminations the book has, the better it is. By choosing a manuscript rich in illuminated details, we give the most value to the money the collector spends on the facsimile.

You can read the full interview with Gunter Tampe here.

Producing a facsimile that contains no images and only written text has almost the same production cost as producing one with illuminated folios. All of the initial work, the printing cost, and the cost of binding are almost the same. Since customers particularly appreciate books with richly colored images, it is rare for books without images to be chosen to become high-quality facsimiles.

Once the manuscript is chosen, publishers sign an exclusivity agreement with the owning library of the original manuscript so that the published facsimile is formally authorized, and the rights won’t be released to other publishers for at least 10-20 years.

Photography According to Strict Quality Standards

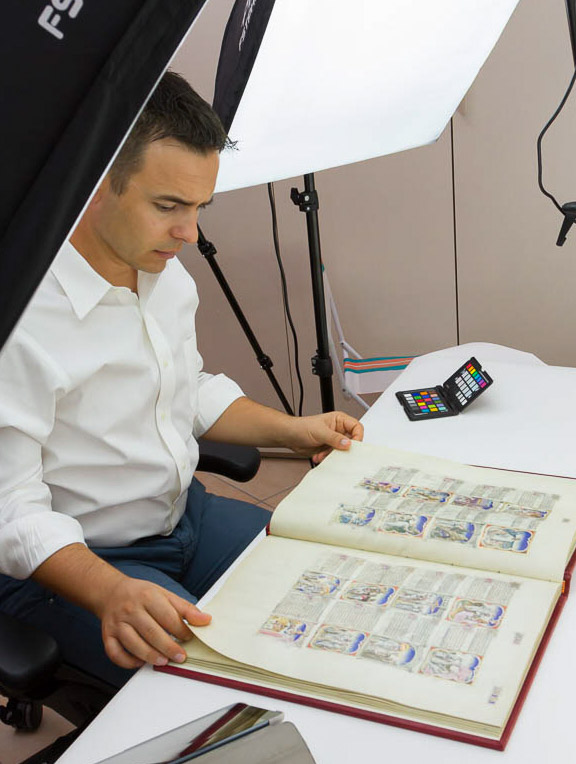

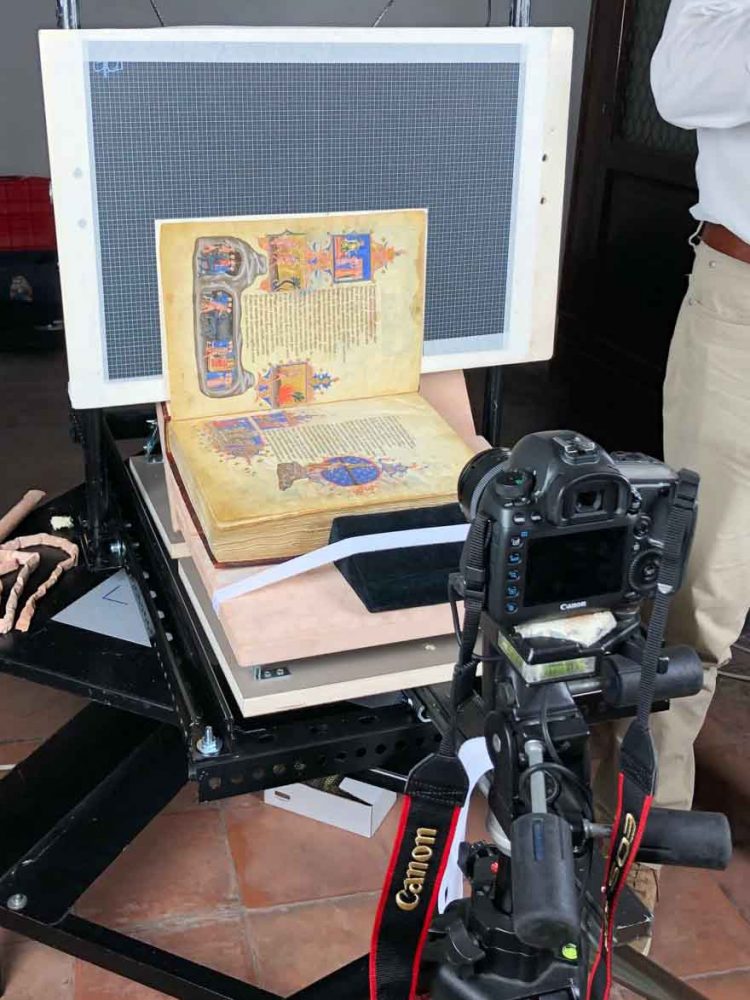

The second step in the production of a facsimile is the photography work. Photography is either executed by the library staff, or by an external staff hired by the publisher. Publishers tend to prefer the second option because they have better control over the outcome of the quality of photos taken. The quality standard of photos for a printed facsimile is much stricter than the quality required for a digitized version.

The most difficult part of photographing manuscripts in order to reproduce them in print is the distortion that is both intrinsic to the object– the manuscript–, and to the technology – the cameras and photography work. You can learn more about distortion in our article “Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: Liability or Asset?”

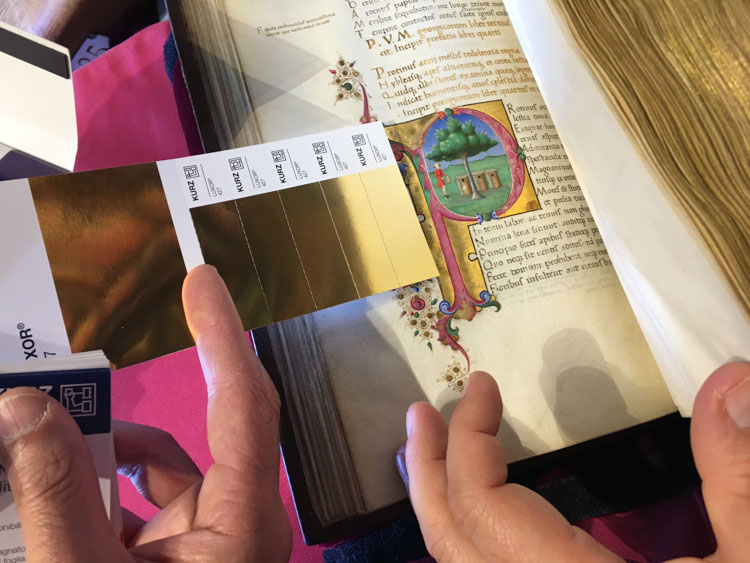

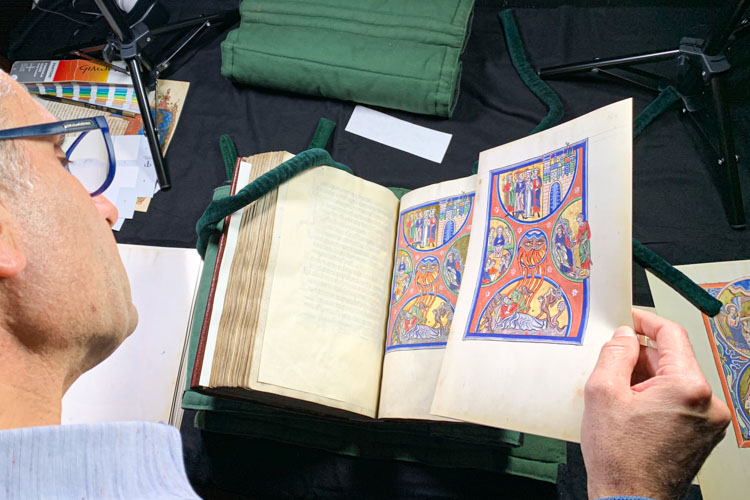

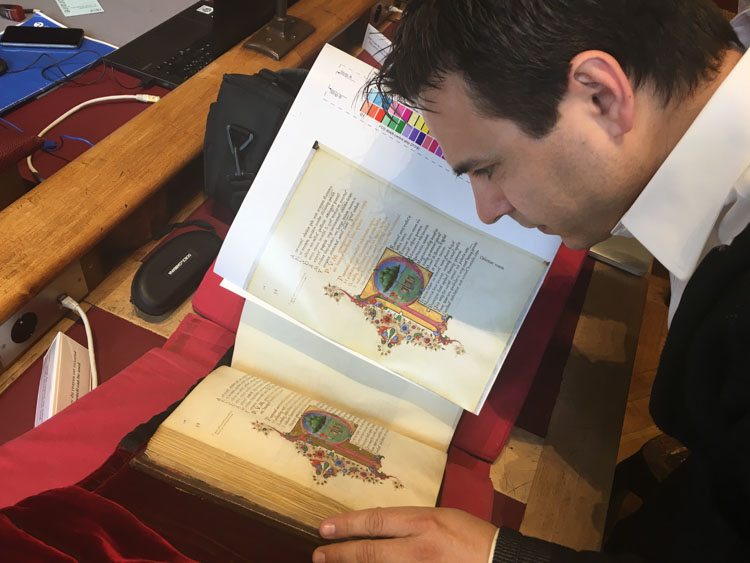

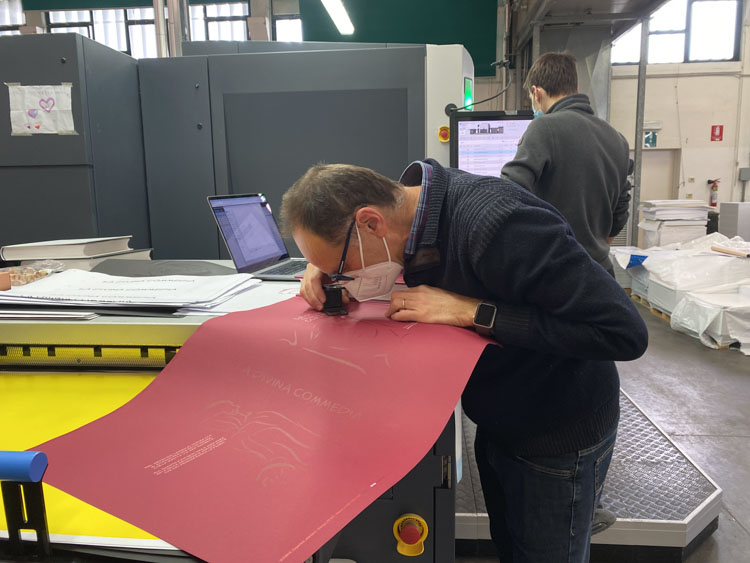

Pre-Press: Getting Rid of Distortion and Adjusting Colors

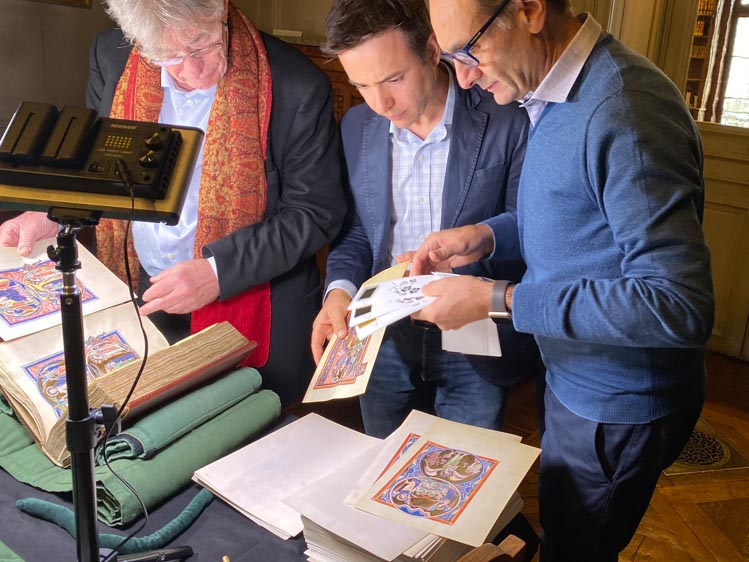

Pre-Press is the third step in producing a facsimile. In this step, Pre-Press Technicians fix the distortion originating from the photographic process, as well as digitally adjust colors after referring to the original manuscript in comparison to physical color patches. This often requires multiple trips to see the original manuscript in its owning library in order to make sure the printed proofs are truly as faithful as they can be to the colors in the original. Make sure to check out our article on my color-proofing trips to the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal to see the Psalter of Blanche of Castile for a more in-depth look at this process!

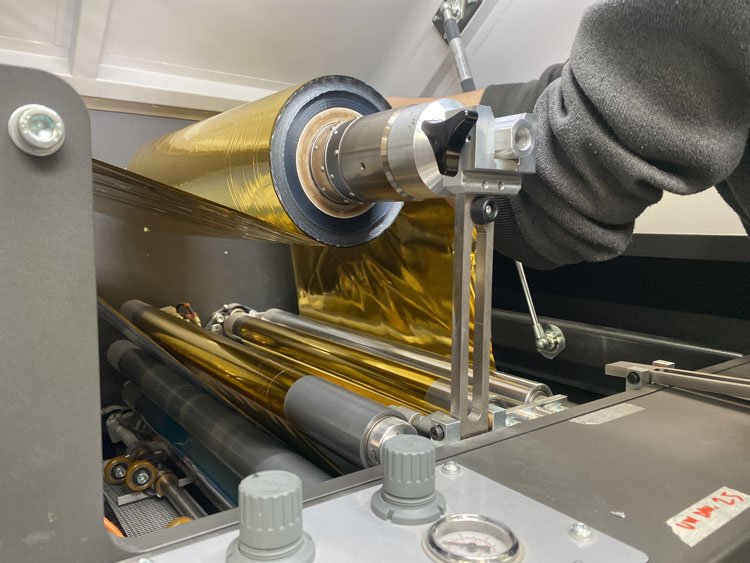

Printing on High-Quality Paper with the Ultimate Presses

When all of the pre-press work is done, the next step in production is printing. Printing of deluxe facsimiles happens on the most advanced presses on the market. Even though there are hundreds of such machines scattered all over Europe, there are very few publishers able to use them to print facsimiles. Each new manuscript that becomes a facsimile has its own unique features, and the press staff has to find new ways, new methods, and new workarounds to meet the challenges of a new production.

The choice of paper plays a key role in production. Facsimiles can be printed on many different types of papers, but the most commonly used paper today is called “Pergamenata,” a product by Fedrigoni, a famous paper mill in Italy. The quality of this paper is fantastic, as it feels more like parchment than regular paper – but it also has its own drawbacks. Indeed, it is both very expensive, up to 15 times in comparison to other quality paper, and very unstable from a dimensional point of view, making multi-layered printing very challenging. This leads to why there are very few press technicians who are able to properly print on this special paper and therefore able to print deluxe facsimiles on their presses.

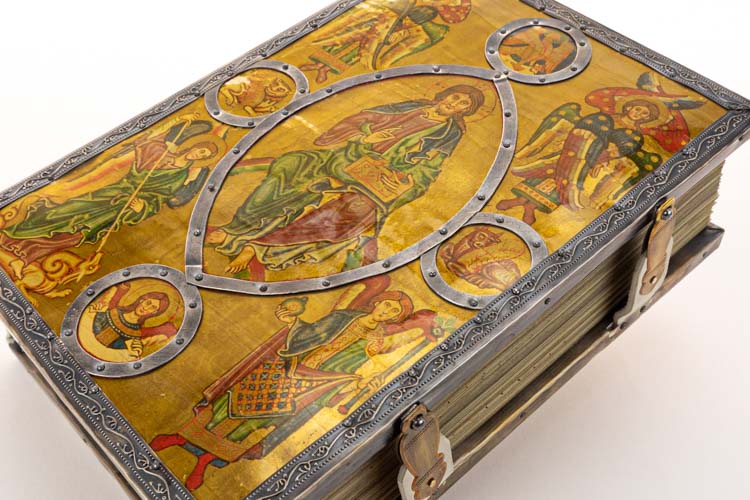

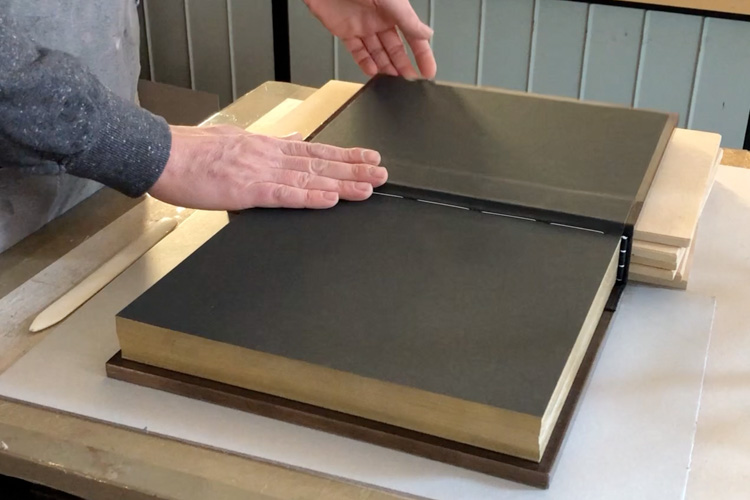

Bookbinding: Craftsmanship from the Middle Ages

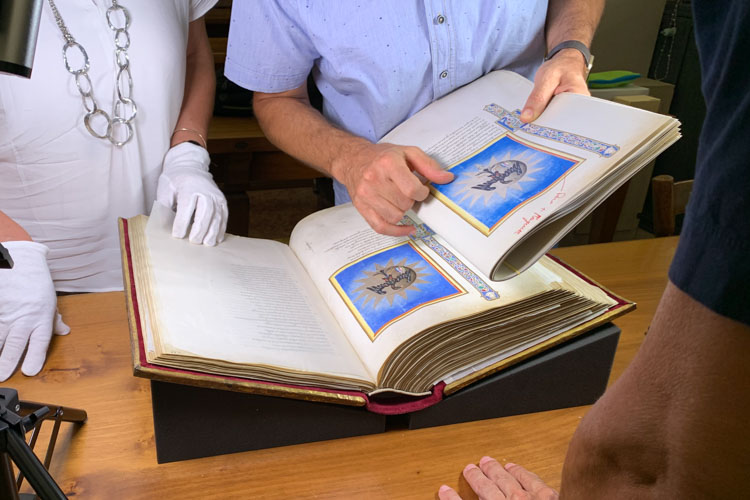

The last step to produce the facsimile actually looks very much like the production of a manuscript in the Middle Ages. Printed flat folios are now cut to shape, folded and collected in gatherings. Finally they’re bound together and the hand-made covers are attached to the book body.

This is one of the most expensive phases of facsimile production, and is still done in traditional book binderies throughout Europe. Traditional bookbinding in Europe is a craft that survives today in part thanks to the facsimile industry.

Classroom Use of Facsimiles: Two Fruitful Cases

In this part of our talk, I spoke about my experience with helping art historian Elizabeth Teviotdale as she was teaching a graduate seminar on codicology and Latin paleography at Western Michigan University in 2020. You can learn more about this experience from Elizabeth’s perspective in her blog post “Teaching Special Collections in the Time of COVID-19”.

Kiana Jones spoke about her experience regarding teaching and research in relation to the medieval facsimile collection at the University of Pittsburgh’s Frick Fine Arts Library. She spoke more broadly about the library as a special place where students from all over the U.S. experienced book art for the first time – in an accessible, hands-on way that they wouldn’t likely experience in a museum or a gallery. She touched on the kinds of questions and discussions that facsimiles generated in the classroom, and focused specifically on her involvement with Professor Shirin Fozi’s exhibition seminar and the challenge of translating materiality for a digital exhibition. You can see the culmination of this project in the digital exhibition “A Nostalgic Filter: Medieval Manuscripts in the Digital Age”.

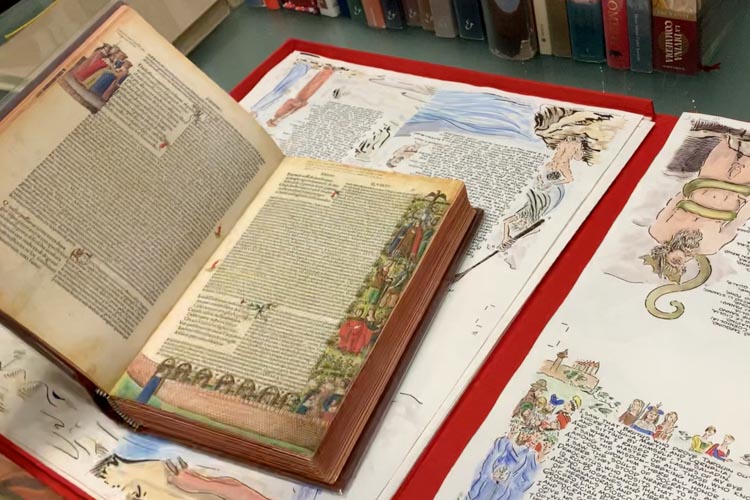

Manuscript Facsimiles in the Studio of an Artist

Lastly, artist George Cochrane discussed his experience using facsimiles throughout the 7-year artistic process of creating his manuscript “La Divina Commedia – The New Manuscript”. He touched more broadly on accessibility of facsimiles, how physically seeing and holding each facsimile was important to the process, and how having multiple Divine Comedy facsimiles open at once helped inform his magnum opus. You can learn more about how medieval manuscripts and facsimiles informed George’s process in this blog post.

Thank You!

I’d like to thank librarians Shalimar Fojas White and Jessica Evans-Brady from the Harvard Fine Arts Library for their invitation to speak at Harvard, and my colleagues Kiana Jones and George Cochrane for their collaboration on this panel.

Interested in having me as a guest speaker at your University to talk more in depth about the production of facsimiles? Send me an email and let’s chat!