The invention of printing is what primarly made the facsimile production possible, but the road was a long and hard one. What difficulties did the printers of the 15th century have to face, and what rewards did they eventually gain?

It’s not easy to make a facsimile: a lot of work goes into providing libraries, book lovers and collectors with the volume of their dreams. How can publishers reach their goal of making a true facsimile of a precious ancient book, so that everyone can enjoy the beauty and the riches the written tomes provide? Let’s see how it all began.

The Invention of Printing

Let us first approach the phenomenon of this book type from a historical perspective. Since the idea of making a facsimile is linked solely to the possibility of reproducing a manuscript for the first time as the relevant, existing technical means allow, then we would also have to start the facsimile’s history where our recording of printing begins.

Undoubtedly, the first printers strove to capture all the formal characteristics of the handwritten book in a form that could be reproduced ad infinitum. At the beginning of the printed book, the explicit wish was to have it match as closely as possible a handwritten codex. Originals were to be imitated and experienced vicariously.

This meant that the new technology’s possibilities were not used at their fullest. The moveable type was employed too much – more than ten times the letters in the alphabet. Abbreviations, ligatures, which were technically superfluous now, were cast in great abundance, just to approximate the manuscript look.

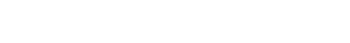

At the dawn of the printing history we find many printed books that attempted to mirror the appearance of manuscripts, as is the case of typological codices editions, the Biblia pauperum or the Speculum humanae salvationis. The Liber de Laudibus Sanctae Crucis by Hrabanus Maurus, first printed in 1503, represents a fine example whose 9th century marvelous picture poems had to be faithfully reproduced.

What mattered here was not the reproduction of individual versions – such as those made for the archbishop of Mainz, for the pope or for the emperor – but only their shared content, which also imposed formal outward requirements.

The Year 1600 – A New Kind of Book is Born

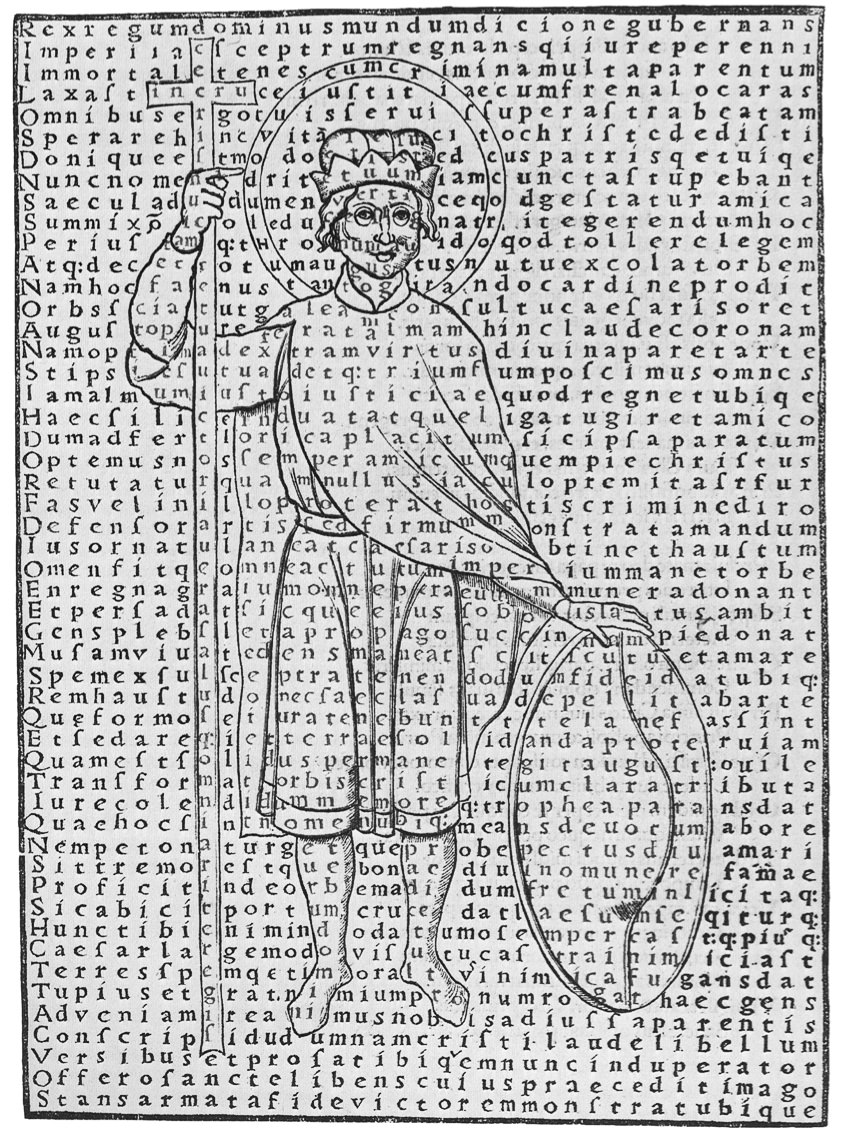

It is not until the 17th century that we encounter efforts to reproduce certain unica in their individual form. The oldest example concerns a Carolingian manuscript that can be found in Leiden today, the Phainomena by Aratos of Soloi (3rd century B.C.), in a Latin version dating from the second quarter of the 9th century.

When he was just 17 years old, Hugo Grotius acquired it and in the year 1600 had the manuscript printed according to the prevailing state of the art in those days. In doing so, he kept to the original’s page makeup, laying out the pictures and text exactly as seen in the original, while having the text set normally in Antiqua and placing the copperplate-engraved pictures next to it. He even adhered to the original dimensions. In his Aratea, Grotius laid out the pictures and text exactly as seen in the original.

Today, this Aratea in the Latin translation by Claudius Caesar Germanicus – the very same famous Carolingian Leidner manuscript with its 39 full-page miniatures – exists in a contemporary facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag. Where the reproduction in 1600 caused damages to the original still visible to this day, modern methods of making facsimiles guarantee the complete protection of this repository of transmitted classical knowledge.

Bumps on the Road

The 17th century also saw some less felicitous attempts at documenting individual manuscripts. For instance, the French antiquarian Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, circa 1620, desired to publish all the miniatures in the famous Cotton Genesis, which we can see today nearly destroyed due to a fire, and had the first copper engravings made. This edition, however, was just as little in evidence as the copper engravings edition of the miniatures from the Vergilius Vaticanus commissioned by the Roman antiquarian Cassiano dal Pozzo. In the Acta Sanctorum (collected Acts of the Saints) of the 17th and 18th centuries there were also many attempts to emphasize individual manuscripts and to document their pictorial decorations.

Thülemeyer’s Bulla Aurea

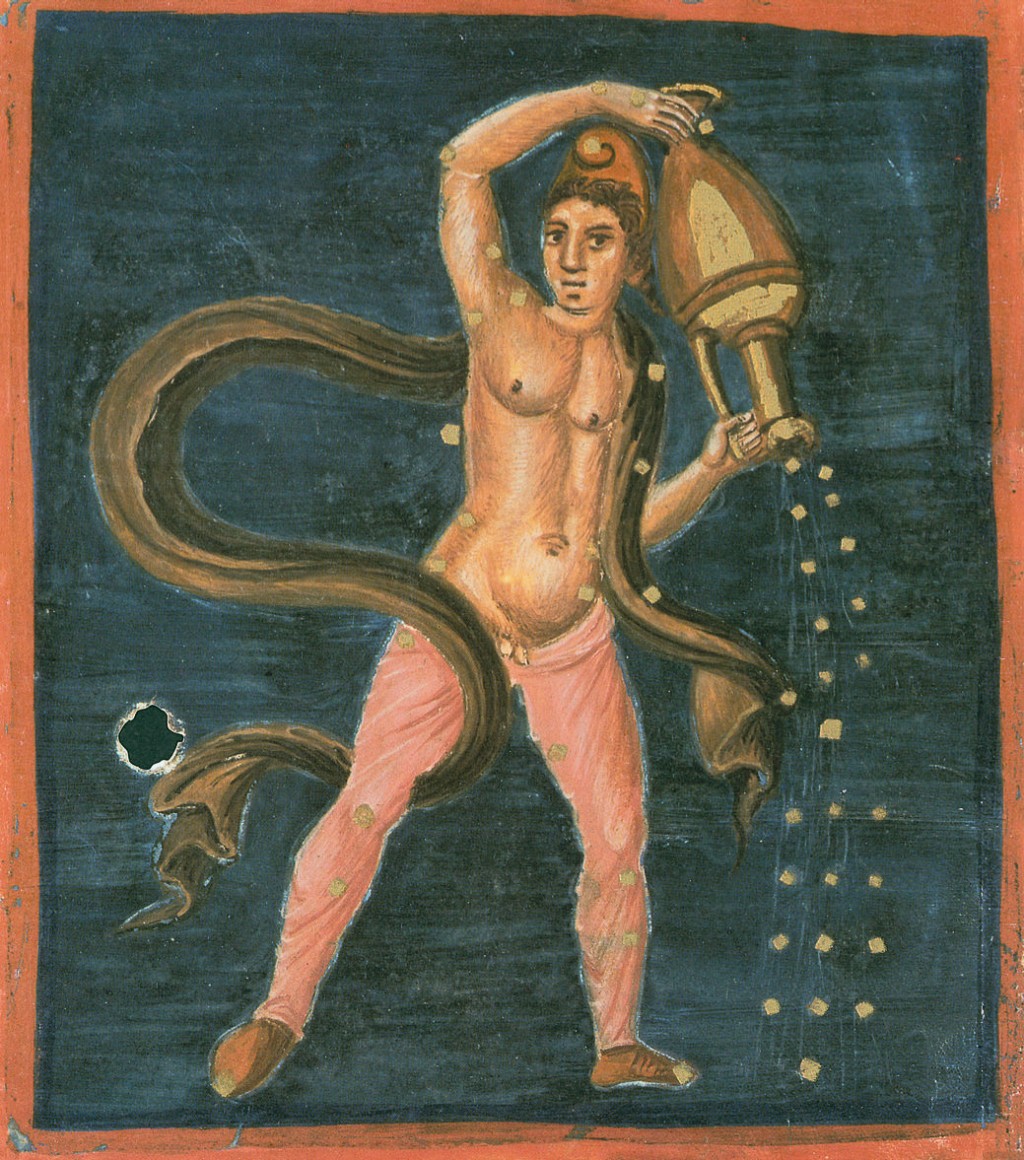

Only as the 17th century drew to a close it is possible to speak of another successful attempt at making a facsimile that resembles our modern conception. In 1697, the law historian Heinrich Günther Thülemeyer published his Tractatio de Bulla aurea (Treatise on the Golden Bull) through Friedrich Fleischer in Frankfurt. In the second part of this book we encounter the Copia Manuscripti Aureae Bullae Carolinae, quod in Augustissime Bibliotheca Caesarea Vindobonensis investitur ….

For this edition, the publisher came up with a very clever process that respond to modern ideas of making a facsimile and built on the ideas of Hugo Grotius from the Leidner Aratea. First, he had all of the manuscript’s miniatures engraved in copper in the original format and the text set identically line by line in Antiqua.

His concept of making a facsimile went so far as to match exactly the text and picture areas to the original format. Only the initial capitals were not individually engraved in copper, but instead were taken from the printer’s inventory. The rubrications were accentuated as well by setting them in cursive type. Thülemeyer only made an exception when it came to the Golden Bull’s title page: here he had the text and picture reproduced in the original size by a single copper engraving.

As is usual and mandatory for modern facsimile editions, Thülemeyer wrote a detailed commentary on the manuscript’s documentation, which today forms part of the holdings of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek under shelf number 338. In his commentary, Thülemeyer even had the ex libris of Emperor Friedrich III, from year 1444 – the famous AEIOU – reproduced, this too in the original size, in order to clarify the manuscript’s history and its outward appearance. He was thus also the first one to make the book’s cover part of the creation of a facsimile.

Conclusions

The history of facsimiles doesn’t end with the end of the century, but whatever innovation the following years have brought must wait till next time. Have some more info on this topic? Let us know and don’t forget to visit facsimilefinder.com to see an example of the very special Golden Bull!

Coming Next..

- The Story of Faksimile Verlag, Publisher of Fine Facsimile Editions – part 1

- Facsimiles and the Role of Illuminated Manuscripts: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 2

- What is a Facsimile: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 3

- How it All Began: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 4

- From Analog to Digital: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 5

- The Making Process of a Facsimile: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 6

- Challenges and Magic of Facsimile Production: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 7

- Binding, Paper, and Commentary: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 8

- Treasures of the Past: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 9

- Gems of the Middle Ages: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 10

- Flemish, Burgundian, and Biblical Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 11

- Middle Ages through the Manuscripts: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 12

- The Challenges of Gothic Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 13

- Ottonian and Charlemagne’s Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 14

Subscribe to Our Newsletter