Did you know that ancient cooking manuals contained humor and parody? Or why Dante called one of his poems “The Banquet”? Take a peek in the kitchens and dining rooms of bygone centuries!

When we think about happiness, one of the first sights that pop into our minds is a rich table filled with all kinds of sweet and savory specialties, a good bottle of wine, with a large group of family or friends sitting around it. In all of human history, people have prepared and enjoyed food not just for nourishment, but also to establish social relationships. Humans become what they eat, yet what they eat is what they are — by consuming food, every society absorbs parts of their culture.

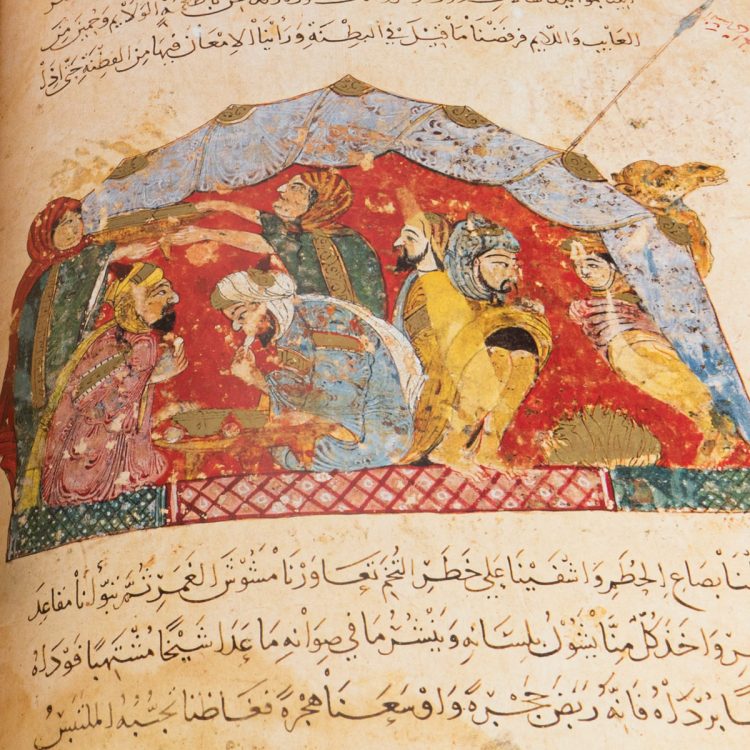

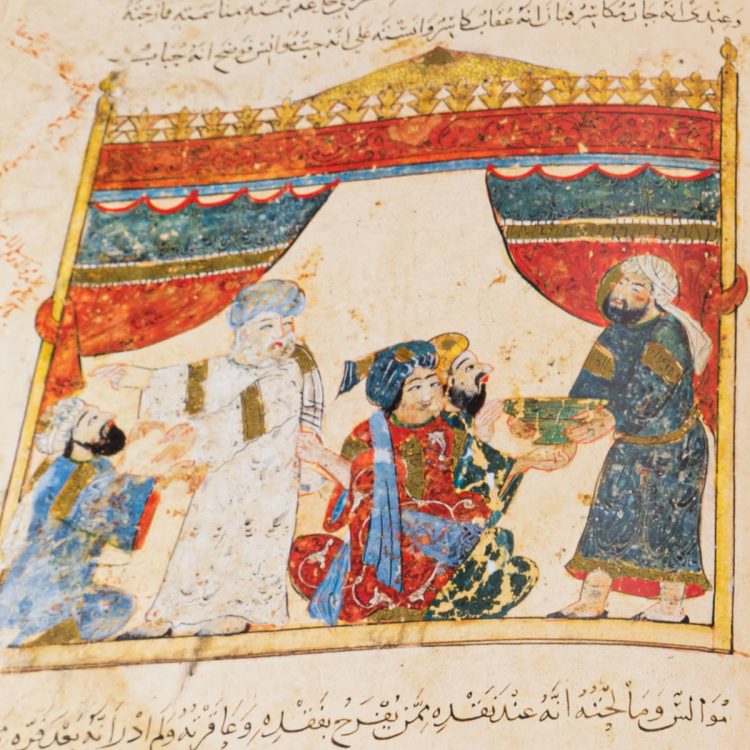

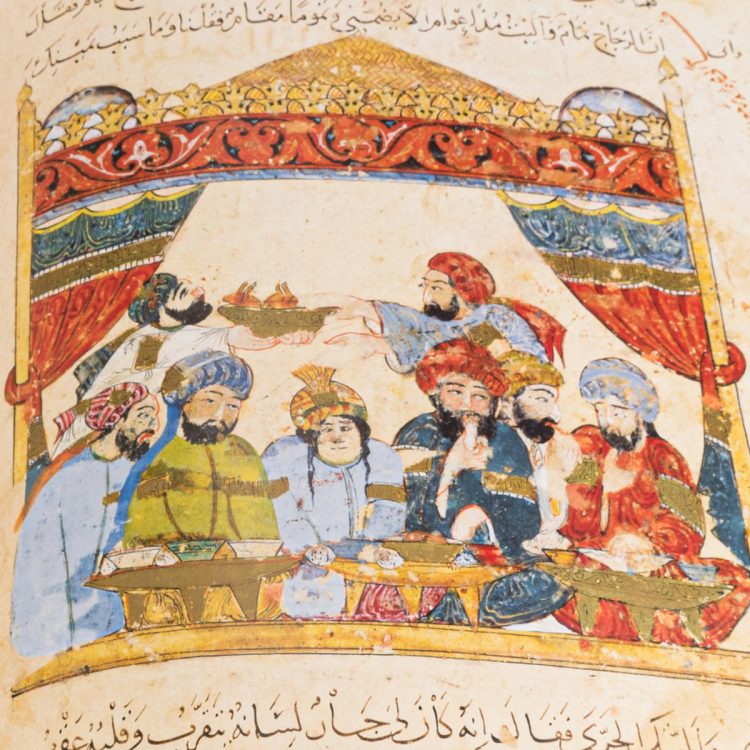

Cooking raw ingredients represents a transition from nature to culture and even from nature to society — food is naturally raw and cooking it is a form of cultural development. Our species probably started developing social skills while eating and talking around a fire. The word “conviviality“, often referring to a friendly atmosphere during a meal, comes from the Latin terms cum (together) and vivo (live). Since the oldest times, taking part in a banquet meant feeding not just the body with succulent game dishes, but also the soul with poetry readings and music.

In the 1st century BC, the Roman biographer Cornelius Nepos praised his friend and patron of the arts Titus Pomponius Atticus with the words:

At his banquets no one ever heard any other entertainment for the ears than a reader; an entertainment which we, for our parts, think in the highest degree pleasing; nor was there ever a supper at his house without reading of some kind, that the guests might find their intellect gratified no less than their appetite.

Dante Alighieri called one of his best-known works Convivio, “The Banquet“. In the 1304 poem, he offered a “banquet of culture” not to intellectuals, but to ordinary people who had not had the chance to study, in the hope that they would “feast on knowledge“.

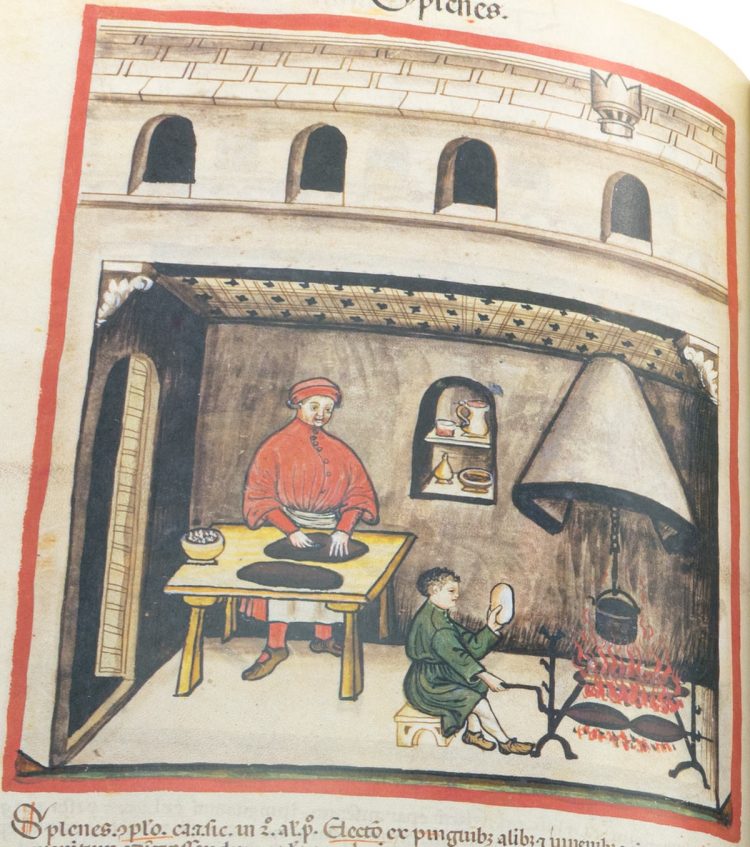

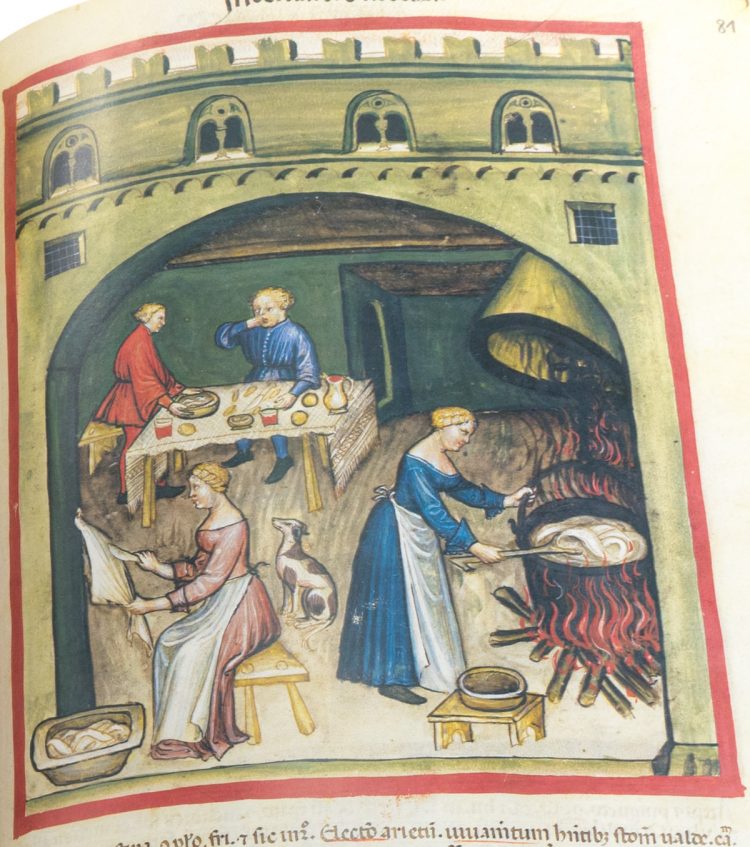

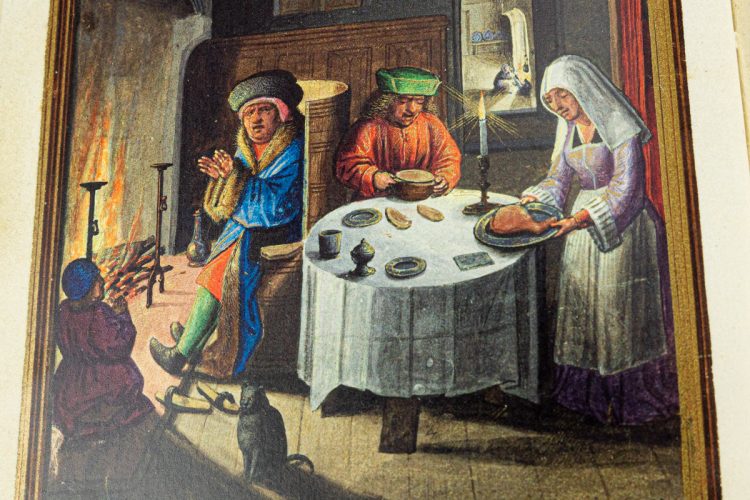

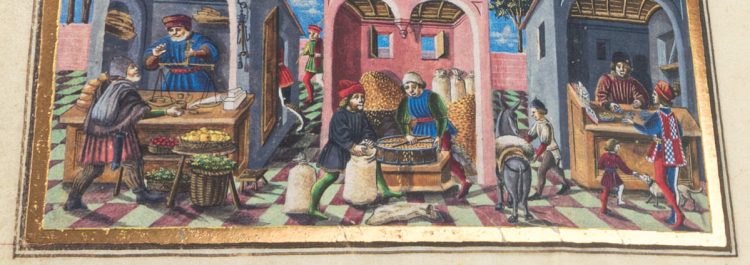

For thousands of years, eating has been related to power, identity, and belonging. Every society in all corners of the globe, from the windswept plains of Northern Europe to the lush jungles of Southern America, has decreed strict rituals, recipes, and traditions related to food. The kind and amount of nourishment were — and are — strictly linked to wealth and social class: while Renaissance nobles devoured lavish banquets, their indigent neighbors languished in hunger.

In specific social situations, the shape of the table stands for hierarchy: in English and other languages, a “round-table meeting” refers to a discussion among equals. In past centuries, even serving one part of the meal instead of another could determine a shift in power relations.

Meals can also define the social roles and connections among those present. Medieval monastic communities used to dine together in the refectory, whereas hermits refuse to share food as a symbol of separation from the rest of society. Even nowadays, working lunches favor business or diplomatic relations.

In certain societies, especially in the past, men dined sitting around a table while women served the food. Cooking manuals provided not just recipes, but also information on the condition of women and their role inside and outside the household. Ever since their origin, recipe books provided a chance to elevate human beings through idioms and proverbs, aphorisms and moral principles, while also mocking those who drank alone, trusted the wrong people, and ate too much, warning them that listening to one’s stomach rather than to one’s brain often proved unwise.

This article is partly based on the volume La Tavola racconta… Dal nettare degli dei alla cioccolata del re, edited by Giovanna Lazzi and published in partnership with the Riccardian Library in Florence and the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities.