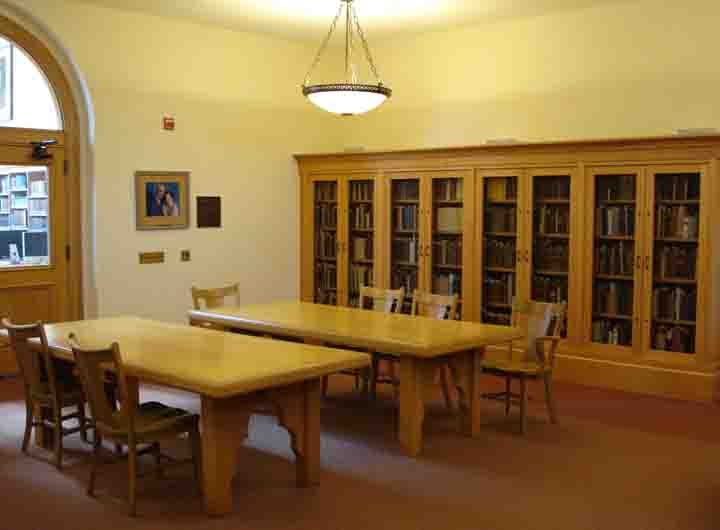

Have you ever sat in the Barchas Room at the Special Collections in Stanford and witnessed a real teaching class with a brilliant Faculty? Well, I did, today, and I was thrilled!

Last year, during my 40-day trip through North America, I met Professor Elaine Treharne at the Department of English of Stanford University. She’s a delightful person and I was very pleased to talk to her about facsimiles I was promoting at the time.

During the meeting, we discussed the different approaches publishers have in producing their facsimiles; while saying goodbye, she mentioned she would have been interested in having me participate in one of her classes at Stanford.

And a year later…

Today, almost a year later, I was sitting in the Barchas Room at the Green Library with Professor Treharne, 11 students and a couple of guests. *gulp*

The lesson was part of Professor Treharne’s course The Material Book: a course whose aim is to “(literally) deconstruct the material book and examine its inventiveness; its metaphorical capaciousness; its role as icon, fetish, container, weapon and monument of collective memory.”

She takes the materiality of books very seriously and you might want to have a look at her blog and the scaring story of a mutilated manuscript she shared with the world.

Eleven students able to stay sharply focused for a 3-hour lesson

The lesson started at 2pm and went through different phases, over the course of 3 hours. It was striking to see how 11 individuals were able to stay sharply focused for what I believe is a very long period of time for such a highly demanding mental activity. Professor Treharne certainly has the great merit of clarity, with that extra bit of humor that made the lesson engaging and pleasant.

First, the students were asked to read from a 12th century excerpt of a manuscript; each student read a phrase and the discussion was mostly focused on abbreviations and how to treat them in transcription. Then, Professor Treharne went over Gothic scripts, explaining the differences and showing how to write some letters on the blackboard.

Facsimile + iPhone: the perfect match to present a manuscript

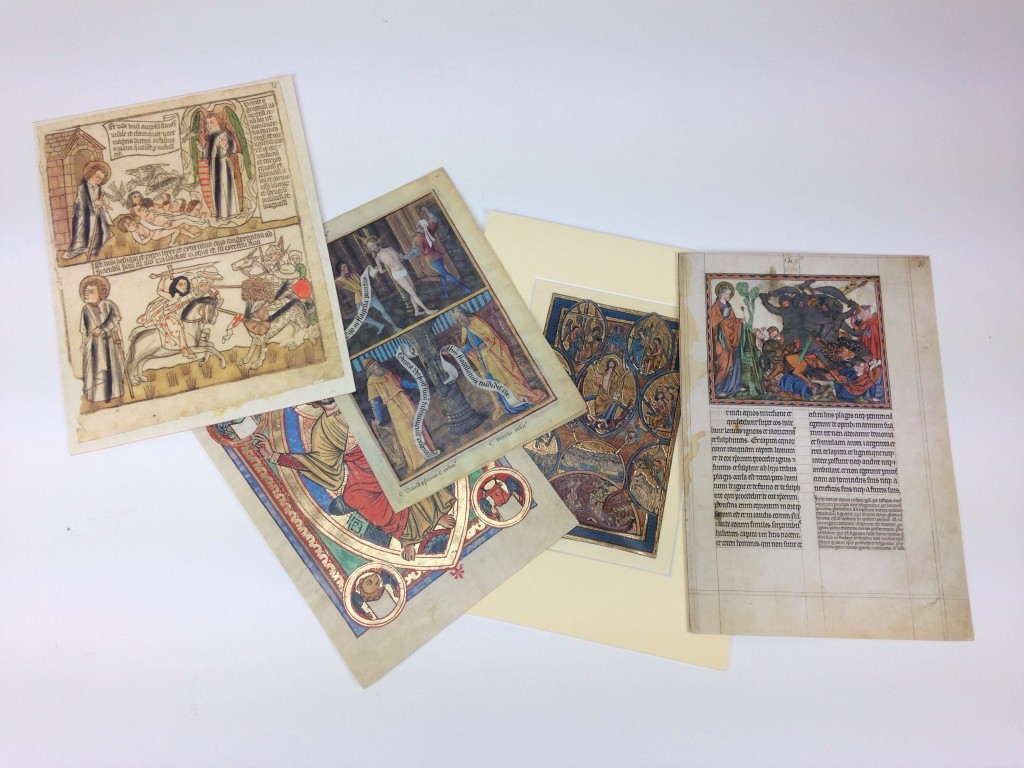

After a short break a student, Christine, made a brilliant introduction and survey of the Codex Calixtinus: she used the facsimile (Kaydeda, 1995) opened on a specific page with neumatic notation, and her iPhone, playing a recording of the page’s 3-voice canon. An interesting mixture of media to discuss the history and features of a manuscript preserved 9140km away from us.

Then, it was my turn. *re-gulp*

What are facsimiles good for?

I started with an excusatio non petita begging for forgiveness on any weirdness in my English and proceeded with my main point:

What are facsimiles good for? In other words: how can a facsimile be useful for a scholar who works in a digital environment?

The answer is seemingly a simple one: the facsimile edition of an original manuscript we have not access to, is the means that allows us to have the closest experience we possibly can of that specific ‘relic’.

Facsimiles are lossy (as every reproduction is)

The problem is that the production of a facsimile is, like every reproduction, a lossy procedure. The visual and physical data has to change its status two or more times, losing details at each passage.

I tried to make my point through a comparison:

when we go to an orchestral performance (concert), the experience we get from the physical movement of the air “pushed” by instruments is a strong one, and certainly different if we listen to that very same performance a month later on the most fabulous hi-fi system. Why?

Are the most fantastic speakers able to reproduce the sound of a full orchestra?

Well, a hundred musical instruments create an amount of waves that are captured by hi-tech microphones; even if the microphones are the state of the art in technology, they’ll never allow the perfect recording of all the subtleties of a live experience (something is lost.)

Wait, it’s not over! The analog or digital signal we get from the microphones has then to be reproduced, and even if it’s on the best speakers on the market, is it enough to live the same experience we had at the concert hall? No, everyone will tell you that it’s great to listen to music at home, when we have a minute, without driving miles to reach a concert hall, but no, it’s not the same experience. There’s something missing.

Facsimiles are recordings of beautiful documents and they do their best in order to re-create the experience with all the limits a reproduction has.

The production of a facsimile edition

In order to explain the difficulties in creating a facsimile, I quickly went over the main steps in its production:

- the act of taking photos of the original document

- “pre-press”: the digital manipulation of the visual data, in order to prepare it for the printing press

- the actual printing and treatment of paper once it’s printed (trimming, aging, etc.)

- book-binding

Each steps deserve a post (and maybe more) alone, so I’ll keep that as future homework for the blog.

What’s in a word: speechless emotions thanks to facsimiles

Once I ended my description, some facsimiles were passed to students and Professor Treharne asked them to use a single word to describe what they just saw and heard. I’ll write those words in the order I remember them, which is most likely the order of importance in my memory:

- uncanny

- noisy

- realistic

- laminated (ugh!), but in a good sense (phew!)

- luxurious

Lastly I got some questions, and I clearly remember the last one, by Adam:

What can’t facsimiles replicate that we can only experience in originals?

A lot, if you ask me.

And I would have loved to leave a concluding thought to this brilliant group of people, but time ran out and so I’ll leave it here, for their eyes to read:

the beautiful imperfection of original documents, which is partially reproduced by facsimile editions and very partially conveyed by digital images, is an experience that we must crave for and try to experience as much as possible because there are no real substitutes to that experience, but only surrogates that can increase the desire to actually reach for the original work of art and satisfy our need for beauty and knowledge.