Fellow facsimile lovers, here is a treat for you: the finished version of an essay on the topic of distortion, soon to be featured on the Essays & Studies Series published for The English Association by Boydell and Brewer. I hope you’ll find it interesting!

The aim of this paper is to analyse the concept of distortion in relation to the transmission of textual objects through the creation of facsimiles. The general claim of the paper is that, paradoxically, distortion is an essential means to get rid of distortion; this concept will become clearer as we explain the different kinds of distortion that we encounter in the process of producing a facsimile edition of a medieval manuscript. Each type of distortion comes from a specific stage of the facsimile-making process.

As we retrace the process from start to finish, we will describe the four main stages of production – namely photo-set, pre-press, printing, and binding stage. Each stage will be discussed in relation to the type of alteration it causes or deals with. With reference to practical examples, it will be argued that distortion can be either positive or negative depending on context, use and aim. A sequence of manuscripts will be taken into consideration to further demonstrate how distortion plays a main role in the art of facsimile-making.

Starting from the definition of perception as the means by which we determine alteration, there will be a discussion of how the use of different colour systems can lead to different outcomes, in terms of perception and distortion. This discussion will take place in the context of the pre-press and printing stages. The latter will allow us to talk about how perception is fundamental in order to create a facsimile; although based on science and technology, it can be safely stated that the process of facsimile-making is far from being an exact science and it involves technical skills, art and craftsmanship in almost equal measure. For example, the process of colour proofing is a testament to such abilities and it relates to the concept of distortion, for its purpose lies in limiting such distortion to create a printed facsimile as close as possible to the original document.

One last aspect of distortion will also be mentioned, that is the “commercial” or exogenous one. With this terminology we are indicating nothing less than the alteration of facsimiles to the point where they cannot longer be considered as such. They gain new features and lose some old ones, all with the aim of making the product more attractive to the general public and to buyers, but to the detriment of historical and stylistic accuracy.

Finally, the paper will come to a conclusion claiming the complementary nature of printed facsimiles and digital scans. It will be stressed how the former, because of its etymology (meaning “make it similar”), needs to be as close as possible to the original, as opposed to digital images – a ground-breaking scholarly tool – which, however, cannot make up for the lack of physicality that can only be conveyed by the tangible object.

1. How Does Distortion Positively and Negatively Affect the Facsimile-Making Process?

Depending on the context, use, and aim, distortion can present itself as positive or negative.

Negative distortion affects the perception of the object of interest in a way that impedes the knowledge of such object. Positive distortion is a set of actions put in place by the makers of a facsimile in order to rectify negative distortion. In extreme cases, negative distortion can be deliberately applied by the very makers of the facsimile, for various reasons.

We will focus on three main types of distortion: endogenous, digital, and exogenous – each belonging to specific stages of the making process. The endogenous distortion belongs to the photo-set stage; the digital one to the pre-press and printing stages; and finally, the exogenous one to the printing and binding stages. We shall focus on each step to understand whether it affects positively or negatively the textual object and/or its making process, specifically in the context of facsimile production.

1.1 Endogenous Distortion

The first stage of facsimile-making is the photo acquisition, in other words taking photos of the object. This is the stage where we are to deal with “endogenous” or material distortion: it means that the alteration is caused by factors within the object itself. We must keep in mind that the scope of the paper is to analyse the inherent defect in relation to the process of duplication of a manuscript, and in no way represents a critique to the object’s nature per se.

The aim of photo-acquisition is to obtain images that will be used to produce the facsimile. Such images must be compliant with several technical requirements to allow the process of facsimile production to be successful. In the context at hand this type of distortion, which can prove to be potentially problematic, is sometimes still manageable and controllable.

To clarify, by factors within the object itself we mean features (alterations), depending on the material and the state of the writing support, that inherently distort the original that is being replicated. We should point out that the writing support we deal with is not the standard modern book as we know it; instead, we find ourselves facing codices, scrolls, or even papyri, and all of them present an innate level of distortion.

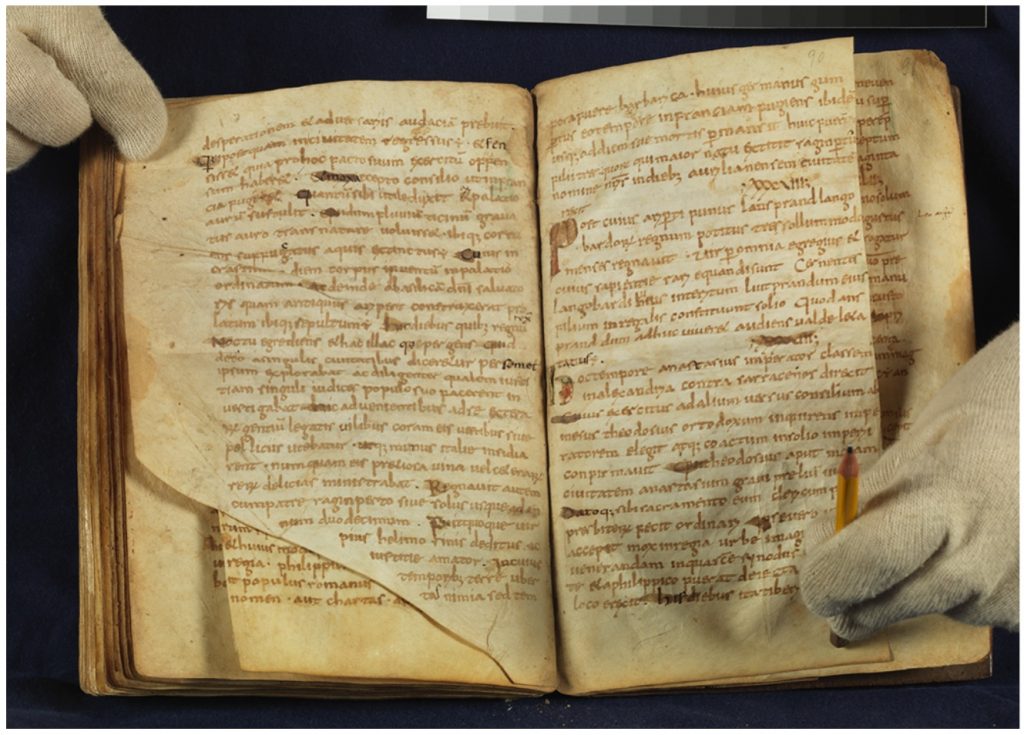

Particularly in this field, hand-made physical objects such as manuscripts bear several points of inherent distortion: at the gutter, for example, pages are bending inwards; parchment is usually wrinkled, with holes and defects; at times, single folios may have been sewn in, leaving a stub that by partly covering the following page hinders the photographing process. One could argue that these alterations be eliminated in order to produce a defect-free replica: however, the purpose of a facsimile is not to improve the original but to replicate it with all its flaws and defects. To do so, the team involved in such a process has first to normalize some of the complexities, to then recreate them.

1.1.1 Endogenous Distortion in Structure and Format of the Manuscript

To better illustrate the aforementioned statement let us examine a practical example. All of us have come across books particularly difficult to keep flat open due, for example, to a tight binding. Taking photos of a manuscript that can’t be forced flat open is challenging and results in images that represent the pages in a distorted format. To minimize this type of distortion, specialists use several means: among others, custom-built stands that keep the manuscript folios as flat as possible, in order to limit the distortion while keeping the binding safe (Fig. 1). Images obtained from an “undistorted” object will allow, at the end of the process, the replica to have, if not the same, then a similar endogenous distortion. This is ultimately the aim of every good replica: to give the beholder a similar experience of the original object.

The Oxford Menologion, with its series of miniatures revealing an extensive use of gold leaf, represents a good case study of another instance of endogenous distortion. Indeed, when dealing with manuscript facsimiles, more often than not we come across illuminated manuscripts. The term “illuminated” comes from the Latin illuminare, “to enlighten or illuminate”, which means to embellish a manuscript with the use of luminous colours (especially gold and silver).[1]

When faced with these valuable decorations, specialists of the field must come to terms with the issues they bring along with their beauty. The gold leaf, which is gold hammered into thin sheets, poses special problems while capturing photos of the manuscript. The light coming from the powerful lamps used to illuminate the manuscript reflects on the golden features of the miniature, leading to an undesirable shimmering that damages the quality of the photos (Fig. 2). This “negative” distortion is usually rectified by taking more shots of the same page from different angles (Fig. 3), giving the digital artist the means to accurately reconstruct the gold patterns in the facsimile edition to obtain a good representation of the original manuscript.

Both parchment cockling and gold leaf shimmering are negative to begin with, for they can potentially hinder the facsimile-making process; however, they can be controlled and managed leading to a product that undergoes a “counter-distortion”. Counter-distortion is usually obtained through manual (as in the case of flattening a folio with cockling) or digital processes (as in the case of gold reconstruction).

1.2 Digital Distortion

Once the photos of the manuscript are shot, the following step is to digitally work the images in order to obtain printing files. At this stage we meet the second type of distortion – namely the digital one.

Digital distortion may be described as negative or positive depending on the context: positive digital distortion is the use of tools to manipulate digital information in order to achieve a result; digital distortion becomes negative when, due to its inherent technical limitations, it affects the final printed product distancing it from the original.

The tools employed to create the positive distortion are, in themselves, neutral. The positive aspect of digital distortion consists in the technical skills and craftsmanship that specialists and experts apply to produce a facsimile that is as close as possible to the original. When managing this type of distortion, we are dealing with the struggles specialists have to face to avoid a misrepresentation of the item. Misrepresentation, we argue, is very possibly an inherent feature of digital imaging software; however, we shall focus on this aspect later, when comparing facsimiles and digital scans.

The standard definition for the word perception is “awareness of the elements of environment through physical sensation”.[2] Thus depending on our senses perception can be positive or negative; if we take the definition a step further, we may consider it as the means by which we determine alteration between two things, and it has a leading role when comparing a facsimile to an original manuscript. In the facsimile-making process perception is fundamental, especially at certain stages such as pre-press editing: what eventually gets printed somehow depends on the perception of the individual operating the machines. In this context, the role of perception is discussed in relation to the way colour systems have a leading role in the pre-press and printing processes, potentially resulting in a distortion originating in digital technology.

1.2.1 Colour Systems Explained

Knowledge of colour systems is useful in understanding the substantial differences between looking at a digital scan on a screen and looking at an object such as a manuscript or a facsimile. The technology underlying digital photography or printed/painted objects determines the perception we have of the physical object when examined on a screen in digital format or in real life. There are two main colour systems: the additive colour system and the subtractive colour system.

Computer screens, cameras and television use the additive colour system (Fig. 4): in this system, creation of images is based on the emission of light. Indeed, computers use backlit screens, composed of millions of tiny lamps made in three colours: red, green and blue. Each lamp can turn from completely off up to fully bright. Millions of lamps (or pixels) together, seen at a proper distance, create the illusion of images on the screen.

Keeping in mind that in the additive system, it is the screen that emits light, we shall proceed on to the second system, the subtractive colour system. In comparison to the additive colour system, the subtractive system (Fig. 5) is to be considered a steady and unvaried system, in that since the beginning of time it has always been used by artists to paint a manuscript, or presses to print colours, and, in general, by whomever created an image using colour on a surface. This system – based on a clear support and, in the case of a manuscript, clean parchment – creates images by adding layers of colours onto the support itself.

The substantial difference between the two colour system is that, while in the additive system light comes from within the emitters, in the subtractive system light comes from an external source, rebounds off the painted support and is reflected upon our eyes. The source of light affects our perception of colours and the idea is that the products of these two different systems are ultimately unparalleled, offering two different experiences.

Awareness of such systems allows us to understand the role distortion plays in the making of a facsimile. In fact, in the production of a manuscript facsimile there are at least two major changes of colour system: the procedure starts from a painted manuscript, which is an object made in the subtractive system; images of the specific object are taken using a digital camera, which works in the additive system; then, the digital information is post-produced on the computer, which we know is an additive system; finally, when the facsimile is printed, the digital information is converted back into the subtractive system.

Moving back and forth between different colour systems tends to create “negative distortion”, specifically distortion of the textual object and its representation in both the digital format and the printed format of the facsimile. The only means of contrasting such distortion is through the technical and artistic skills of print-makers (i.e. positive or counter- distortion). When technology falls short, specialists and their know-how come to the rescue and make up for the negative effects caused by the inherent limits of technology.

1.2.2 Negative and Positive Examples of Digital Distortion

The best example of specialist knowledge that solves an unwanted distortion is the expert use of imaging software such as Adobe Photoshop. This software allows the manipulation of digital information to obtain printable files, suitable to be used to produce a facsimile that is as close as possible, in shape and colour rendering, to the original manuscript.

An example of positive distortion is the use of digital imaging software to correct the original manuscript folio’s distortion. As it is not always easy to physically flatten wrinkled parchment during the photo acquisition and the photos of distorted folios would not be usable for facsimile production (Fig. 6), digital software is used to solve such problem. The process could be defined as controlled distortion, and hence can be thought of as positive, for by means of digital distortion applied to the photos, the print-makers are able to obtain printable files in order to produce a facsimile as close as possible to the original manuscript.

The Peterborough Psalter is a beautiful 14th century manuscript produced in the London region by three unidentified artists. The text is laid out in columns and written in blue ink and gold leaf. Photos of the manuscript are not sufficient to produce a facsimile edition of the gold features: gold leaf replica is in fact printed using special machines that apply the material following a specific, pre-determined pattern; the photos alone represent the unified view of the page, and not only the gold text. The printing pattern is determined by the technician who re-draws by hand the gold text and/or illustration onto the screen, creating the stencil to reproduce (Fig. 7 and 7b). The result of his work is a printing plate that will be used to apply the gold leaf replica to the facsimile.

This art is taken one step further when dealing with shell gold which is trickier not only to re-design but also to identify on the original manuscript. In some cases, in fact, this kind of gold can be barely perceptible in the context of the painted image: to create proper printing plates, curators and facsimile technicians carry out an extremely careful analysis of the original manuscript trying to identify every smallest stroke of shell gold on the manuscript.

1.2.3 Colour Proofing and Digital (Counter-)Distortion

It is worth noticing that the pre-press stage is not the only step where perception plays a relevant part, for the printing process is mainly based on it, both from an artistic and technologic point of view. Although art and technology can often be at odds, one claiming superiority over the other, in the field of facsimile-making they are much more allies than enemies, being ultimately complementary. One expression of this is the process of colour-proofing (Fig. 8) when both technical and artistic skills of print-makers are truly put to a test.

This painstaking process entails, at least initially, duplicating the most significant pages and details from the original manuscript and assembling them together in a proofing page (Fig. 9). The page is then printed and closely compared with the original manuscript. As there is no exact or numerical way to measure the difference in colouring between the facsimile and the original manuscript, every print-maker evaluates the quality of the proofing page according to his perception and knowledge.

When he notices that there is an inconsistency between the original manuscript and the proofing page, the print-maker works out the changes that need to be applied to the digital information in order to print a new, and more faithful proofing page. This process is repeated several times to achieve a proofing page that is as close as possible to the original manuscript and that will be the base for the production of the entire facsimile. This process is another example of controlled distortion applied to digital information: at some point in the process, colour information gets altered, and the only way to remedy this is to digitally distort it back. This process is thus an expression of how perception of the individual technician plays an important part in the detecting of shade differences between the original and the facsimile.

1.3 Exogenous or “Commercial” Distortion

After the photo-set, pre-press, and printing steps, we come to the last stage of production of a facsimile, which closely resembles the traditional bookbinding process. This process includes techniques such as cutting to shape, folding, gathering, and binding the book. This last technique makes the case for the last type of distortion we may encounter in the process of facsimile-making, that is the exogenous or “commercial” distortion.

We know that, in the past, luxury covers were sought-after by wealthy sponsors to decorate their manuscripts. In present times human beings have not changed much and appearance is still where the attention concentrates the most, which in our case means focusing on producing a beautiful binding. A large majority of facsimiles are sold to private collectors in Europe and, in order to increase sales to this type of customers, some less scrupulous publishers opt for the production of fake or counterfeit bindings. Producing a facsimile with something substantially different from the original manuscript is, as already stated, a voluntarily distortion that alters the quality of the final product.

Commercial distortion of the binding can unfold in three different ways: first, some publishers research and reconstruct what they believe could have been the original binding – with varying degrees of success in achieving a good result; second, some publishers take a coeval binding from a similar manuscript (perhaps from the same author or workshop), and use it for the facsimile – needless to say that the binding they choose is often much nicer than the one being replaced, looking to make it more pleasant to the eye; the third and final scenario, possibly the worst of all, involves publishers having a “dress to impress” moment: they design a fancy binding, usually with a lot of gold and stones, simply to impress customers and sell more. Luckily, the third group of the “fake binding” distortion is quite rare and mostly occurs with minor, unskilled publishers.

2. Digital Images and Facsimile: Frenemies?

This is the comparison between two important tools: facsimiles – discussed at length – and digital scans. To do so, a personal experience by Roger Wieck, curator of Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts at the Morgan Library, will provide our case study.

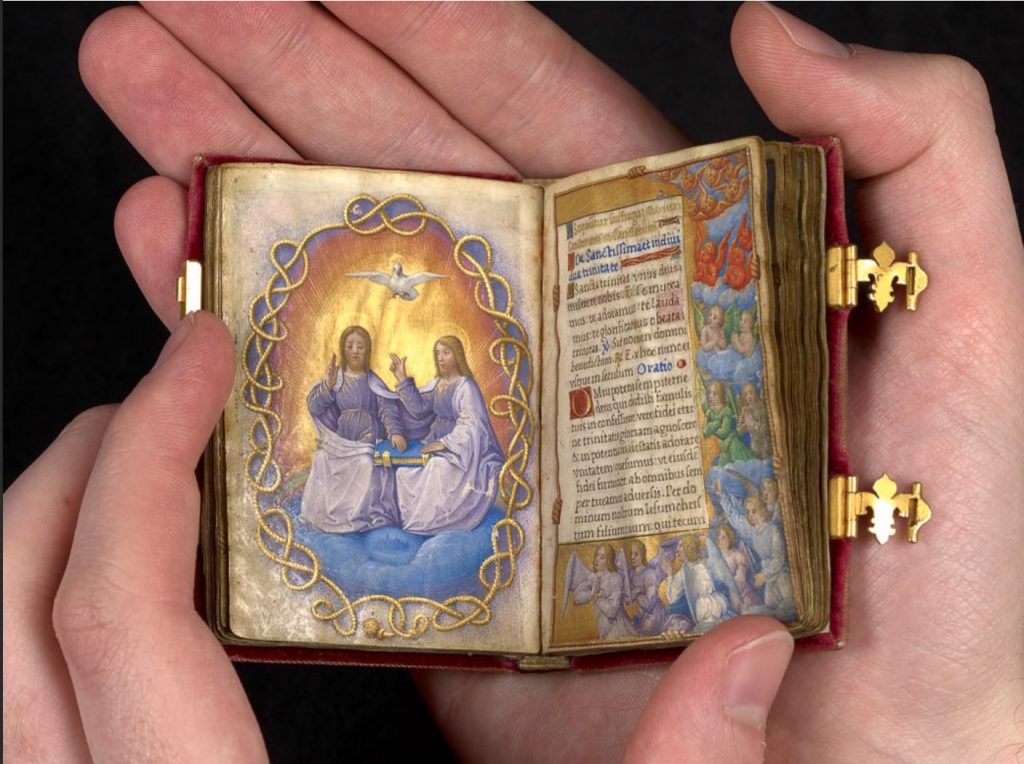

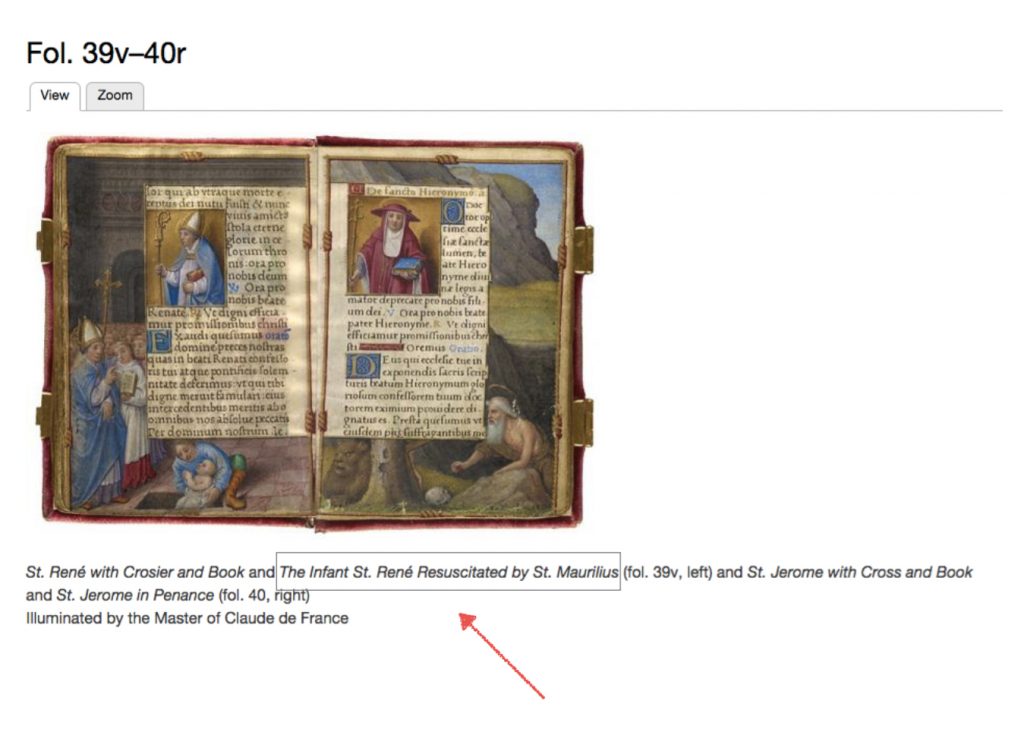

The Morgan library is in possession of a tiny and beautiful illuminated manuscript known as the Prayerbook of Claude de France (New York, Morgan Library & Museum, M. 1166). Less than three inches tall, and two and a half inches wide, it is a testament to the skills of the artists who produced this small and delicate item. This prayer book (Fig. 10) is dated around 1517 and was made for Claude, a woman who had married François de Angouleme in 1514, just a couple of years prior to his coronation. At the time this manuscript was made Claude was struggling to have her first male heir, having already had two girls. Like many queens of the time, she was expected to deliver an heir to the king.

Being this manuscript a very personal object of devotion, we can picture Claude carrying it during this time of trouble in her purse or dress pocket, in very close proximity to her body. Due to its purpose, the object is very small: this, combined with a tight binding, today makes it difficult to keep the manuscript open for proper analysis and, of course, for good image acquisition. Since the miniatures go all the way to the borders, such a fragile manuscript should never be handled more than absolutely necessary: to avoid excessive handling and at the same time encourage scholarship on the manuscript, it became imperative that good copies, both digital and printed, should be made.

In 2010, a facsimile publisher took the initiative and produced an accurate facsimile edition of this delightful work of art. The shooting of the manuscript was not an easy process: with it being so tiny and with such a tight binding, publisher and curator had to get really creative in order to keep the manuscript open without invasive tools, like fingers or polystyrene strips.

The result of the shooting is a set of digital scans of exceptionally high quality, which can be enjoyed for free online by anyone, anywhere, at anytime. Being fully accessible from any internet access in the world is one of the great, groundbreaking advantages of online digital repositories of images. The same scans were used by the publisher to produce the charming facsimile which can now be found in many public and private collections.

Roger Wieck claimed:

The daily companionship of the facsimile of the Prayerbook of Claude de France was inspiring and gave me the opportunity to live with the manuscript almost as Claude de France had done.

Roger Wieck was asked to write the commentary for the facsimile, and he stated that both the digital scans and the printed facsimile played an invaluable role in his work. As curator of the library, Dr. Wieck was entitled to visit the vault, home to the manuscript, as often as he wanted in order to peruse the original for his analysis; at the same time, being concerned with the conservation of the object, he was well aware that handling it more than absolutely necessary would have conflicted with his role of conservator, and put the manuscript at risk.

As he wrote the commentary he was constantly in the presence of the printed facsimile; he kept it on his desk while working, as a sort of “muse”, a pleasant substitute of the original. He claimed that the daily companionship of the facsimile was inspiring, and gave him the opportunity to live with the manuscript almost as Claude de France had done. At the same time, the digital scans allowed him to explore details of the manuscript that could have never been visible to the naked eye.

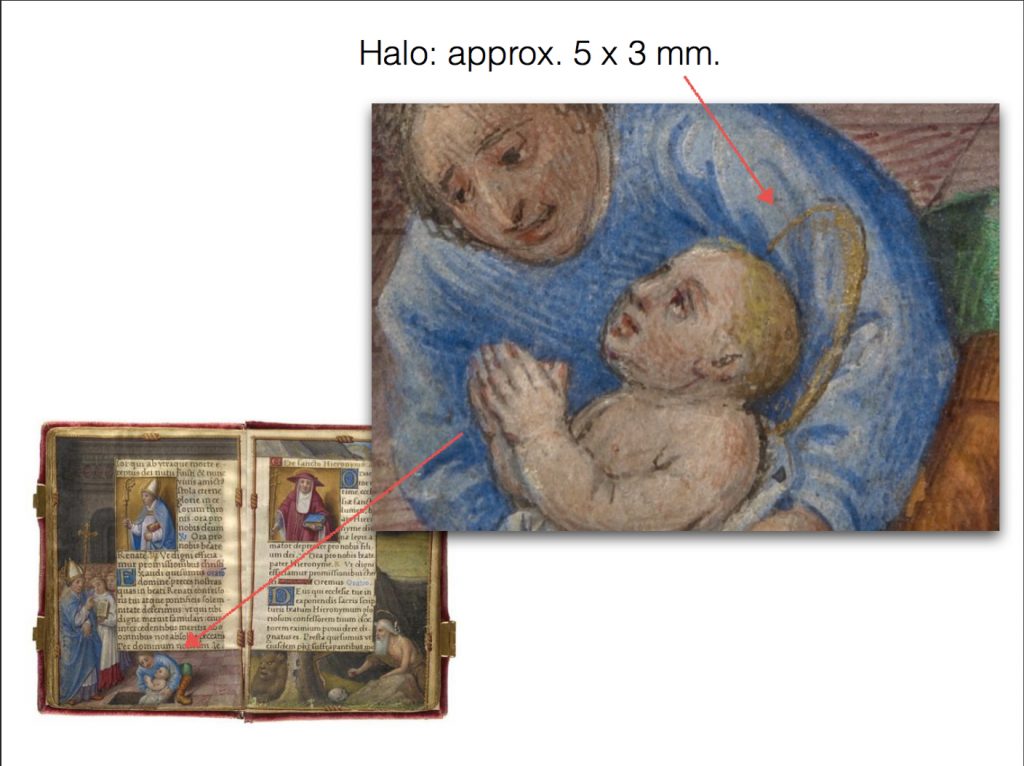

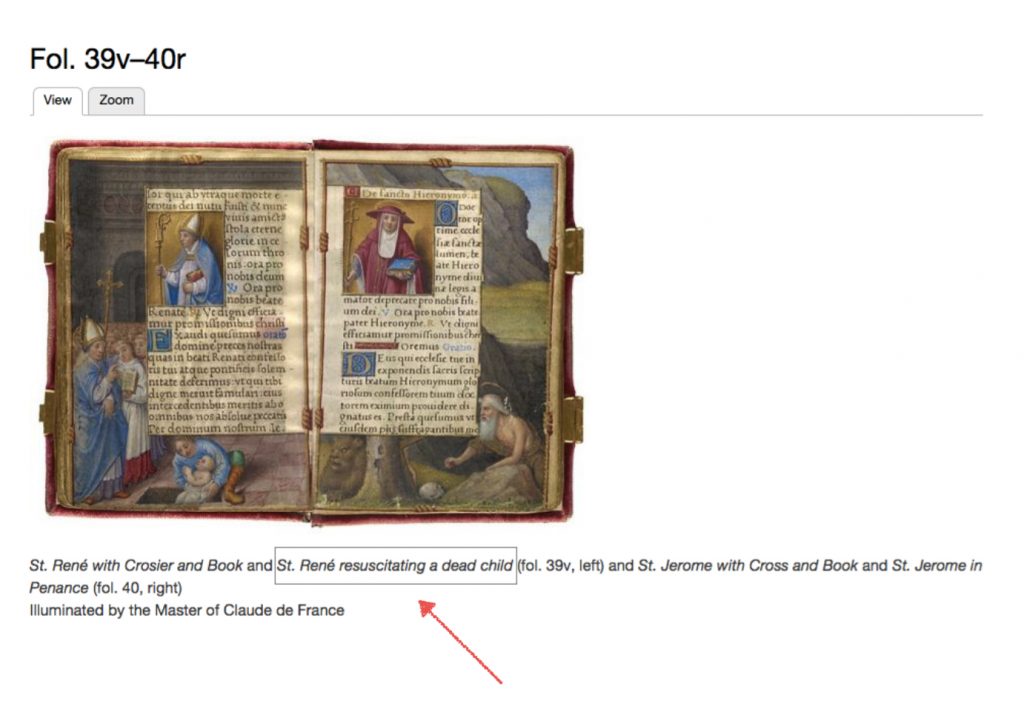

High quality scans can be zoomed to high levels and a close analysis of the miniatures revealed a detail which until then had gone unnoticed. Indeed, Roger Wieck observed the presence of an almost undetectable halo that completely changed the meaning of a painted scene. It is a single, very small stroke of painted gold, so small and blended with other light colours that Dr. Wieck never noticed it during his time with the original manuscript (Fig. 11).

As a testament to the accuracy of this story evidence can be provided; indeed, on the Morgan’s website it is possible to view all the openings of the manuscript with a short caption describing the miniatures. Before the website was updated just after the new discovery, the caption of Folio 39v read: “St. René resuscitating a dead child”, i.e. the meaning that Roger Wieck ascribed to that scene at that time, before observing the halo (Fig. 12). After spotting the almost undetectable feature, the Morgan Library’s curator has changed that caption to: “The Infant St. René Resuscitated by St. Maurilius” (Fig. 13).

A small detail was overlooked because of the understandable anxiety to preserve the manuscript and this essential element might have gone unnoticed, preventing us from having a clear and complete understanding of the scene; only thanks to the analysis of a digital reproduction was this realization made possible.

The conclusion of this story is both simple and staggering: even for scholars with direct access to the original manuscript; both printed facsimile and digital scans are exceptional tools for researching a work of art. Just like art and technology – previously discussed – they have complementary features: digital images are great for close analysis sometimes impossible with the manuscripts itself; printed facsimiles give us the opportunity to live with the object, to witness its physicality, to experience what our predecessors, from the creator, to the commissioner of the book, to the following owners, have experienced with that manuscript in their hands.

We have discussed the advantages that these two tools bring along with them; however, as with all things, nothing is perfect and some drawbacks are to be expected. We will now examine the disadvantages of printed facsimiles and digital images.

2.1 Can the High-Pricing of Printed Facsimiles Be Avoided?

The greatest shortcoming of printed facsimiles is certainly the price, which usually limits the potential library customers only to the wealthiest academic institutions.

However, the cost of production almost always justifies the high sale price: facsimiles are limited editions; every manuscript poses specific replication problems that need to be solved with creative solutions; and finally, the process of production is almost never standard or industrial, thus increasing the final cost of the facsimile.

A good example is the production of the noteworthy Très Riches Heures of the Duke of Berry facsimile, made in 2010 by Franco Cosimo Panini (Italy).

The facsimile was printed on a Heidelberger Druckmaschinen’s SpeedMaster XL 105, a 2-million dollar press produced in Germany (Fig. 14). It takes more than 3 hours to set it up in order to produce excellent quality facsimile pages and print a 1000 copies run of a single printing sheet. The same machine would be able to print 8000 copies of a regular book in a much shorter time, due to the less demanding setup time needed for a normal publication vs. a high quality facsimile.

A manuscript like the Très Riches Heures, 8 by 11 inches and 200 folios, normally fits on 25 printing sheets. In normal conditions, we could calculate to employ 3 hours for each side of the 25 folios, making a total of 150 billable hours of two skilled specialists and the SpeedMaster.

However, the specific case of the Chantilly manuscript is eloquent: in fact, several printing sheets needed to run through the SpeedMaster more than a single time. The most intricate of the pages are so rich in colours and decoration that the facsimile version needed to go through the press up to 18 times to properly replicate all the shades of the beautiful work of art. Including drying times, that single printing sheet containing 8 folios of the manuscript took over two weeks to be successfully completed.

This is just an example of the many that we could consider to explain why facsimiles may be very expensive to the final buyer. Moreover, the printing part is only one of the steps of the process that may take up to 18 months from photos of the manuscript to actual delivery of the facsimile. [3]

In conclusion, printed facsimiles, despite their cost and relatively limited availability, are very possibly the best next thing after original manuscripts, for they allow to experience the objects in their physicality as – one is to hope – they give the best compliance to the work of art they represent.

2.2 Digital Images: a New Era?

Digital images carry some advantages that make them one of the most groundbreaking tools for the study and diffusion of art history. The first and most obvious advantage is that, when publicly shared on the internet (through proper websites or even through social networks), digital images allow the widest access to information that until a decade ago were accessible only through physical movement of the object, or of the user.

The second important advantage is that digital images, when properly produced, allow levels of analysis that the naked eye simply cannot achieve, as we noted in the Prayerbook example above.

However, digital images cannot be considered facsimiles: despite the large amount of information that they are able to convey, they lack important elements of the original object and can mislead the perception and the knowledge of that object.

One caveat: when talking about distortion this paper has paid attention to its choice of words. Indeed, the expression “digital facsimile” was purposely never used, because using the word facsimile for digital images would be somewhat a distortion of the truth. The word “facsimile” comes from Latin and means “make it similar” or “made similar”. “Fac” may be in place of “factum” (made) or may be the imperative of the verb “to make”: in both cases, consistency with the etymology of the word prevents digital images from being considered facsimiles. Since a facsimile is something that is as close as possible to the object it represents in all its aspects, the idea of a “digital facsimile” would defy such definition. We reaffirm and there is no doubt that digital scans are a spectacular tool for teaching and research, but can we truly say that they can be manuscripts’ facsimiles?

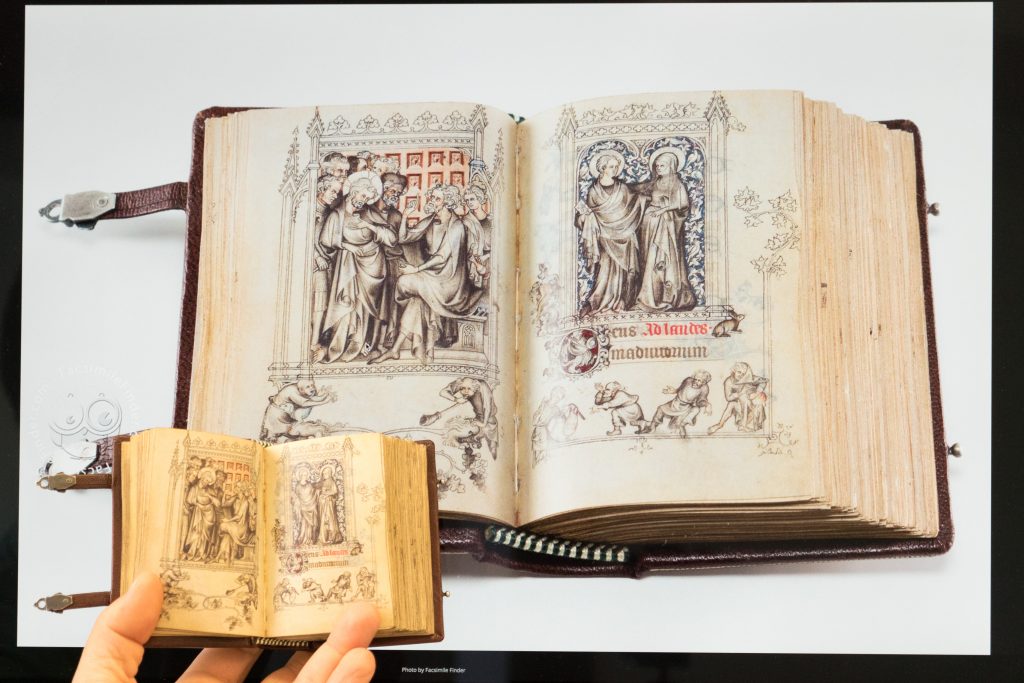

The manuscript Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux is a case in point (Fig. 15). The manuscript originates from the 14th century and was the first major French work to display delicate miniatures in the so-called demi-grisaille technique. The detailed precision of the miniatures is all the more impressive when considering that this codex is one of the smallest books of hours in existence, measuring a mere 3.5 x 2.3 inches. Yet, if one were to look at its digital scans on a big screen, one would not realize its size and as such he would not be able to appreciate it in all its delicacy. The digital scan would not convey all the aspects required by a facsimile, running the risk of misrepresenting the manuscript. Hence, albeit complementary, facsimiles and digital scans are not interchangeable.

This paper would like to encourage the quest for a different term to express the use of digital images in manuscript studies, so as to appropriately define this powerful, yet sometimes limited, tool. Ultimately, digital scans might convey to someone who has never seen a manuscript the distorted idea that an image on a screen is enough to appreciate the majestic beauty of illuminated manuscripts: all who had the privilege to experience a real illuminated manuscript know that the entirety of the object is as important as the beautiful images painted on the pages.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to analyse the concept of distortion in relation to the transmission of textual objects through the creation of facsimiles. This paper claimed that distortion is an essential means to get rid of distortion, that there is more than one type of distortion – namely, endogenous, digital, and exogenous – and that distortion can be regarded as positive or negative depending on context, use and aim. Firstly, we listed the three main types of distortion according to their positive or negative aspect. We explained that endogenous or “material” distortion means that the alteration is caused by factors within the object itself. This type of distortion, albeit potentially problematic, is sometimes manageable, as the case study of the Oxford Menologion has shown.

Furthermore, this distortion has been assessed as negative for it affects the facsimile-making process. The second type of distortion that was discussed is the digital one; it was claimed that this can be positive or negative depending on context. It is considered negative when the inherent limits of technology cause some printed products to be far from identical to the original; its positive aspect consists in the skills, art, and craftsmanship that specialists apply so as to produce a facsimile that is as close as possible to the original. Dealing with this type of distortion means that we are dealing with the struggles specialists face to avoid a misrepresentation of the item.

As case study for the digital distortion we referred to the Peterborough Psalter, a testament to the painstaking craftsmanship and patience of the experts. The last type of distortion dealt with is the exogenous or “commercial” which can unfold in several ways, with the sole aim of making the product more attractive to the general public and to buyers, to the detriment of historical and stylistic accuracy. This last one, of course, was assessed as negative altogether, as it sells something under false pretences. By looking at these three types of alterations, especially the first and the second, we have seen how distortion can get rid of distortion. In the case of the Oxford Menologion, taking more shots of the same page from different angles allowed the digital artist to accurately reconstruct the gold patterns, rectifying the negative distortion. In other words, to get rid of one distortion, namely the shimmering, specialists resort to another distortion, namely taking pictures from different angles, and then reconstructing the object.

The second part of the essay was dedicated to the analysis of how distortion is very much related to perception. Reference was made to the use of different colour systems – namely the additive and subtractive systems. While in the additive system light comes from within the emitters, in the subtractive system light comes from an external source, rebounds off the painted support and is reflected upon our eyes. This results into two different products, offering two different experiences, perceptions, and distortions. It was, indeed, discussed how the changes of colour system in the production of a manuscript facsimile are source of alterations; for this back-and-forth between different technologies allows much room for “negative distortion”. Credit was given to specialists who come to the rescue where the machinery and technology fail. In relation to this, it was stressed how art and technology should not be put to comparison in the field of facsimile-making, as they are extremely complementary, as in the colour-proofing process.

Finally, the paper focused on one last topic: the comparison between facsimile editions and digital scans, with reference to the Prayerbook of Claude de France and an anecdote by Dr. Roger Wieck. From his experience we found out that the daily companionship of the facsimile was inspiring to him, and at the same time, that the digital scans allowed him to explore details of the manuscript that could have never been visible to the naked eye, i.e. a small painted halo.

Just like art and technology, printed facsimiles and digital images have complementary features: digital images are great for close analysis that is often impossible with the manuscripts themselves; printed facsimiles give us the opportunity to experience the physicality of the object. Pros and cons were discussed, resulting into digital scans being more accessible and less expensive than facsimiles, but ultimately conveying a different experience to the user.

The paper also shed light on why we should not refer to digital scans as digital facsimiles: printed facsimiles and digital scans are not interchangeable, and digital scans could never substitute facsimiles altogether, as vice versa. Facsimiles, despite their limits and flaws, can truly enhance manuscript studies appreciation, granting people with no access an unprecedented artefactual experience; indeed, they partially fill in the void left by the absence of the manuscript. Digital scans, on the other hand, give a wide and easy access to images of manuscripts but run the risk of misrepresenting the physical object. Both are essential to the world of manuscript studies and both share a leading role in the field; each provides a different experience but ultimately they are the paramount tools that allow scholars and amateurs to appreciate both the obscure and illuminated past.

[1] Michelle Brown, Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts. A Guide to Technical Terms, Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum in association with The British Library, 1994), 69.

[2] Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. ‘Perception’. Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 11th ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 2003. http://www.merriam-webster.com/

[3] The most recent example that comes to mind is the Voynich manuscript, which, as claimed by the publisher, will be in production for about 18 months.