The only known scroll inscribed on metal, almost 2,000 years ago, has been the protagonist of a long and painstaking facsimile-making process. It took more than 40 years of work on its analysis and restoration, and now, thanks to high-tech tools the facsimile is finally ready. An article written by Facsimile Editions describes the adventure to the discovery of this work of art and the making of its facsimile.

The Copper Scroll, so named after the metal on which it is inscribed, is the only known Dead Sea Scroll inscribed on metal. It gives detailed instructions of the hiding places probably used to conceal the vast Temple treasure before the Romans ransacked the Temple in 70 AD.

The scroll names the locations of the many hiding places and lists a vast inventory of silver and gold but, tantalisingly, does not reveal where to start the search. It provides an independent confirmation of the importance of the Second Temple and is considered to be one of the best sources of first century Hebrew.

Henri de Contenson, a French archaeologist, and Józef Milik, a famous early Dead Sea Scrolls scholar, discovered the Copper Scroll accidentally in 1952 in Cave 3 near Qumran during a survey of the hundreds of caves along the western shore of the Dead Sea. The Copper Scroll was found in two pieces, rolled and buried in the cave. After 2,000 years hidden there, it had corroded and was too brittle to be unrolled.

Forty Years Worth of Work

In 1955, in order to separate and unroll the fragile scroll, the two rolls were sent to the Manchester College of Technology in England where, with a fine saw, they were cut into 23 cylindrical segments.

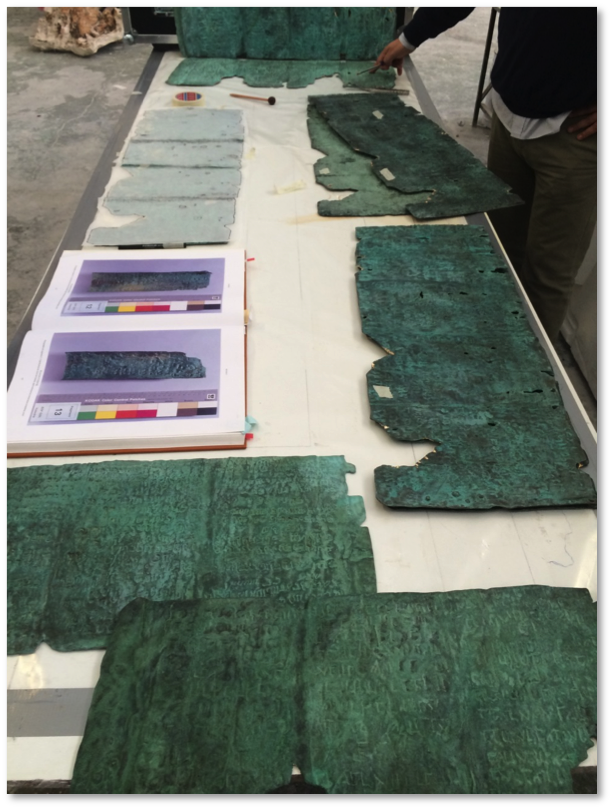

Forty years later, and after further deterioration, the segments were sent by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities to the Laboratoire EDF-Valectra in Paris for restoration and scientific, scholarly analysis. As part of the investigation and restoration, EDF-Valectra created flexible silicone moulds from the cylindrical segments. These moulds were then laid flat and joined to recreate (in negative) the three plates of the Copper Scroll. Using the silicone moulds, EDF-Valectra were able to create electro-formed bright copper plates to exactly reproduce the profiles of the original. Unfortunately, whilst a faithful technical reproduction of the texts, these electro-formed plates conveyed none of the ageing, corrosion or patina acquired over 2,000 years in the desert. Furthermore, the original EDF copies only reproduced the front face of the plates.

Utilising EDF-Valectra’s reproduction, Facsimile Editions of London worked for two years with 3-D imaging specialists, metallurgists and patinators to reconstruct the 23 strips into an aged, solid copper replica of the original scroll. The scroll, in three pieces, is approximately 2.4 metres in overall length and 30cm wide. Made of copper, the precise outline of the edges and holes of the original have been faithfully reproduced and finished by hand.

Using the latest technology the three EDF electro-formed plates were scanned in 3-D. These scans became the ‘master’ and the guide from which the new facsimile was created. Unfortunately EDF-Valectra only reproduced the front of the three plates. We needed to create the backs too.

Based on the knowledge that the plates were made by hammering the letters into the surface, we reversed the scans (effectively now a master for a negative image) to derive the information for the back.

The finished 3-D data files were then used to drive CNC milling machines to rout the pattern into high-density polycarbonate blocks, by far the most accurate and complicated part of the entire process. As far as is known, a double-sided object of this size has never been routed to such fine tolerances.

These routed blocks would become the new ‘masters’ for the lost-wax casting process. Experimentation was required in order to cast the panels to the same size as the original as the casting process causes shrinkage. In order to achieve the target size, several test panels had to be routed with injection waxes and test casts being made at each stage.

In the casting process there is no tolerance – a casting error cannot be retouched – it has to be cast again, and many were! Each panel is cast in sections delineated where they were originally cut during their ‘opening’ in Manchester. They are then reassembled and welded before finishing carefully by hand with direct reference to images produced during EDF-Valectra’s restoration.

Facsimile: a Good Substitute

How accurate is the facsimile? Simply by virtue of the production processes there will be dimensional differences but they are minor. There are also differences in the patina because a patina is a heat and chemical process that it is impossible to apply with either consistency or fine control.

From an electro-formed object we have made something that is as close as it is possible to get to the surface of the original and which imparts the look and feel of an ancient copper object made over 2,000 years ago. The facsimile edition, strictly limited to 20 sets, is presented in specially constructed, heavy-duty cases custom designed to fully protect the scrolls during transportation or long-term storage.