Illustrated manuscripts based on Beatus of Liébana’s commentary on the Apocalypse, the last book of the Christian Bible, offer a unique window into a time when the fragility of life focused the minds of Christians on not only the immediate afterlife but also the time beyond time.

What are commonly referred to as “Beatus manuscripts” are twenty-nine illustrated commentaries on the Apocalypse by Beatus of Liébana. These manuscripts, all in Latin, were produced between the last quarter of the ninth century and the first half of the thirteenth century.

The dedication of physical and human resources to creating so many rich copies of Beatus of Liébana’s text demonstrates the importance placed on spiritual salvation and the reckoning of the soul. These aspects remain timeless and to experience one of these manuscripts is as poignant today as it must have been a millennium ago.

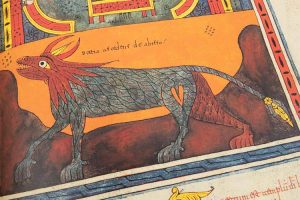

The vast majority were made in northern Spain, the early works being Asturian and Leónese, the later being Castilian. Most are extensively illustrated with brightly colored, detailed pictures showing the events of the Apocalypse and abounding with monsters, angels, and the famous Four Horsemen. It is a rich and unique manuscript tradition that spans three centuries and reflects the ongoing religious, cultural, and political strife of medieval Spain.

Beatus of Liébana and his Commentary on the Book of Apocalypse

Beatus of Liébana was a monk who was born ca. 730 and lived and wrote in the Kingdom of Asturias until his death ca. 800. He was highly influential in eighth-century Christian philosophy as a teacher to Alcuin of York and influential politically in his role as confessor to Asturian royalty. He was a powerful opponent to the adoptionist Christology debated at the time, which argued Christ was the adopted son of God, thus denying the Incarnation.

His most famous work is his commentary on the Apocalypse, written in 779 and revised in 784 and 786. The commentary was widely read throughout Western Europe and Beatus of Liébana’s somewhat cynical but hopeful message flavored with contemporary similes and sayings makes the work personal and relatable thus adding to its popularity.

The Beatus Model

The earliest Beatus manuscript was almost certainly illustrated and served as a model, direct or indirect, for all that followed. This initial manuscript likely adapted iconographic conventions from early Christian Apocalypse images, as reflected in the Trier Apocalypse.

The illustrative cycle of the archetypal Beatus manuscript includes 108 canonical images, seven images relating to the commentary text including the mappa mundi, eight prefatory images of the evangelists, fourteen pages of diagrams charting the geneaology of Christ, and a final eleven illustrations for the commentary on Daniel. Additional images such as the Alpha and Omega were often included.

The nearly three dozen surviving Beatus manuscripts and fragments are kept in libraries and cathedrals throughout Western Europe and North America. Although few today can read the Latin text, the illustrations bursting with their colorful beauty and monstrosity are as enigmatic and engaging as ever.

Although there is a well-understood model for manuscripts based on Beatus of Liébana’s commentary on the Apocalypse, each copy is unique and presents the illustrations with their own format, colorations, and inclusions.

Picturing the Apocalypse

The fantastic events of the last days have piqued the imagination of artists throughout the Middle Ages. The partnership of the biblical text, Beatus of Liébana’s commentary, and its images is central to the Beatus manuscripts. While the paintings can certainly function as visualizations for the memory, they are not straightforward illustrations, nor could they be with creatures such as beasts with seven heads and places such as heavenly cities.

Indeed, they served as guides for the imagination of future calamity and unmaking, providing a concrete starting point for ruminations on what is to come. Indeed, Maius, the illuminator of the Morgan Beatus, wrote

I have painted in series pictures for the wonderful words of its stories, so that the wise may fear the coming of the future judgment of the world’s end.

Early Beatus Manuscripts

Nine illustrated Beatus manuscripts survive from the tenth century. Their painting style is due to the combining of influences from Carolingian Christian and Iberian Islamic sources. The interlaced initials and figural illustration follow practices of manuscript production from Insular and Carolingian monasteries, yet stylistic details such as horseshoe arches in depictions of architecture and the preference for geometric rather than vegetal patterns are influences drawn from the local Iberian traditions.

Bold, earthy colors and a distinctive figural style create a unique pictorial tradition.

Late Beatus Manuscripts and Royal Patronage

Whereas early Beatus manuscripts tended to be of monastic origin and for monastic use, copies of the later twelfth through the thirteenth century, while still monastic in origin, enjoyed royal patronage. The early Iberian style gave way to new influences, especially the Byzantine influence found in western Romanesque art and later the International Style of European princely courts.

Instead of executing faithful copies of both text and illustration, this later group sees greater divergence in artistic style. This gives late Beatus manuscripts a greater resemblance to other works from European areas—such as England and France—rather than being distinctively Spanish in style.

Extant Illustrated Beatus Manuscripts and Fragments

after John William’s census, published posthumously in 2017.

| Manuscript | Date | Origin | ||

| Silos Fragment | Last quarter of the 9th century | Northern Spain (Asturias? San Millán) | ||

| Morgan Codex | ca. 940–945 | San Salvador de Tábara | ||

| Vitrina 14-1 Codex | Mid-10th century | Kingdom of León (San Millán de la Cogolla?) | ||

| Valladolid Codex (=Valcavado Beatus) | June 8 – September 8, 970 | Kingdom of León (Monastery of Valcavado?) | ||

| Tábara Codex | July 27, 970 | San Salvador de Tábara | ||

| Girona Codex | July 6, 975 | San Salvador de Tábara | ||

| Vitrina 14-2 Fragment | Second half of the 10th century | Kingdom of León | ||

| Urgell Codex | Last quarter of the 10th century | Kingdom of León | ||

| San Millán Codex | Last quarter of the 10th century and first quarter of the 12th century | Castile (?) and San Millán de la Corolla (?) | ||

| Escorial Codex | ca. 1000 | San Millán de la Cogolla | ||

| Facundus Codex | 1047 | León, royal scriptorium (?) | ||

| Fanlo Codex | ca. 1050 (17th century copy) | San Andrés de Fanlo (?) San Millán de la Cogolla (?) | ||

| Saint-Sever Codex | Third quarter of the 11th century | Saint-Sever-sur-l’Adour | ||

| Burgo de Osma Codex | Begun January 3 or June 3, 1086 | Sahagún, Monastery of Saints Facundus and Primitivus | ||

| Turin Codex | First quarter of the 12th century | Catalonia (Girona or Ripoll?) | ||

| Silos Codex | April 18, 1091 and July 1, 1109 | Santo Domingo de Silos | ||

| Corsini Codex | Second quarter (?) of the 12th century | Sahagún, Monastery of Saints Facundus and Primitivus | ||

| León Fragment | Mid-12th century | Kingdom of León (region of Astorga?) | ||

| Berlin Codex | 12th century | Southern Italy | ||

| Manchester Codex (= Rylands Beatus) | ca. 1175 | Castile (region of Burgos? Toledo?) | ||

| Cardeña Codex | ca. 1180 | Castile | ||

| Lorvão Codex | 1189 | Monastery of Saint Mammes, Lorvão | ||

| Navarre Codex | Late 12th century | Navarre (?) Astorga (?) | ||

| Las Huelgas Codex | September 1220 | Toledo (?) Santa Maria la Real de Las Huelgas (?) | ||

| Arroyo Codex | ca. 1200–1235 | Region of Burgos (?) | ||

| Rioseco Fragment | 1200-1250 | Castile (?) | ||

| San Pedro de León Fragment | ca. 1000 | Kingdom of León (?) | ||

| Milan Fragment | Mid-11th century | Southern Italy | ||

| Geneva Codex | Mid-11th century | Southern Italy |

Bibliography

Williams, John. Visions of the End in Medieval Spain: Catalogue of Illustrated Beatus Commentaries on the Apocalypse and Study of the Geneva Beatus, ed. Therese Martin. Late Antique and Early Medieval Iberia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

Williams, John. The Illustrated Beatus: Corpus of the Illustrations of the Commentary on the Apocalypse. 5 volumes. London: Harvey Miller, 1994–2003.

Revenga, Luis, ed. Los Beatus. Exhibition Catalog. Chapelle de Nassau, Bibliothèque royale Albert I, 26 September – 30 November 1985.

Mundó A. and M. Sánchez Mariana. El Comentario de Beato al Apocalipsis. Catálogo de los códices. Madrid : Joyas Bibliográficas, 1978–1980.

Neuss, Wilhelm. Die Apokalypse des Hl. Johannes in der altspanischen und altchristlichen Bibel-Illustration. Das Problem der Beatushandschriften. [Spanische Forschungen der Görres-Gesellschaft. Reihe 2. Bd. 2/3]. Münster: 1931.