There are only three extant Beatus of Liébana manuscripts written and illustrated outside the Iberian Peninsula: the Berlin codex is, among them, the most peculiar. By Peter K. Klein

The Romanesque Beatus of Liébana in Berlin

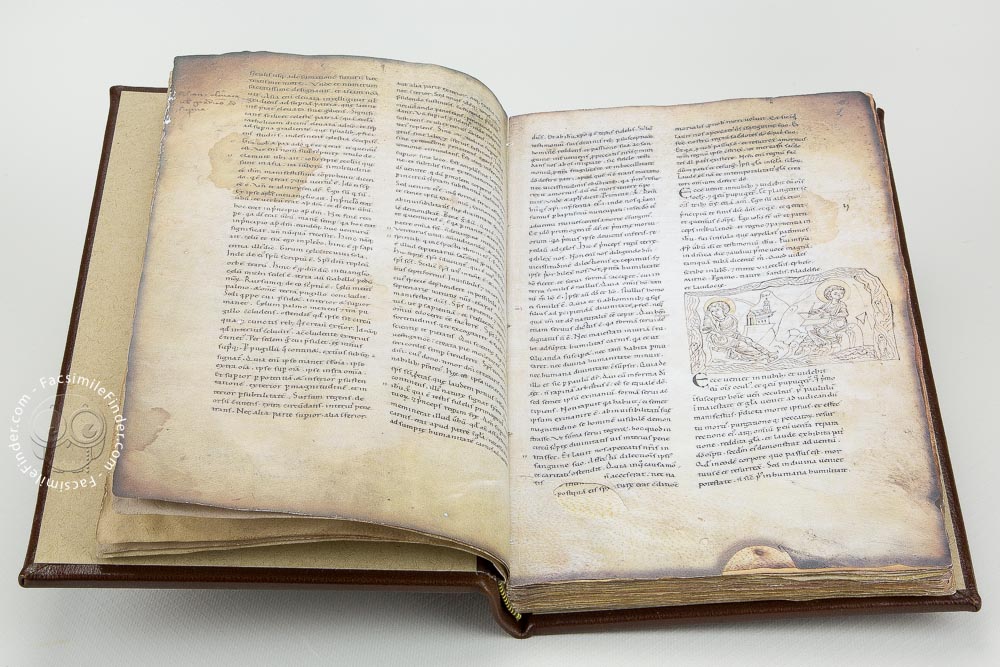

The Romanesque codex of the Beatus of Liébana preserved in the Staatsbibliothek, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, in Berlin (Ms. theol. lat. fol. 561) is one of the only three extant Beatus manuscripts written and illustrated outside the Iberian Peninsula.

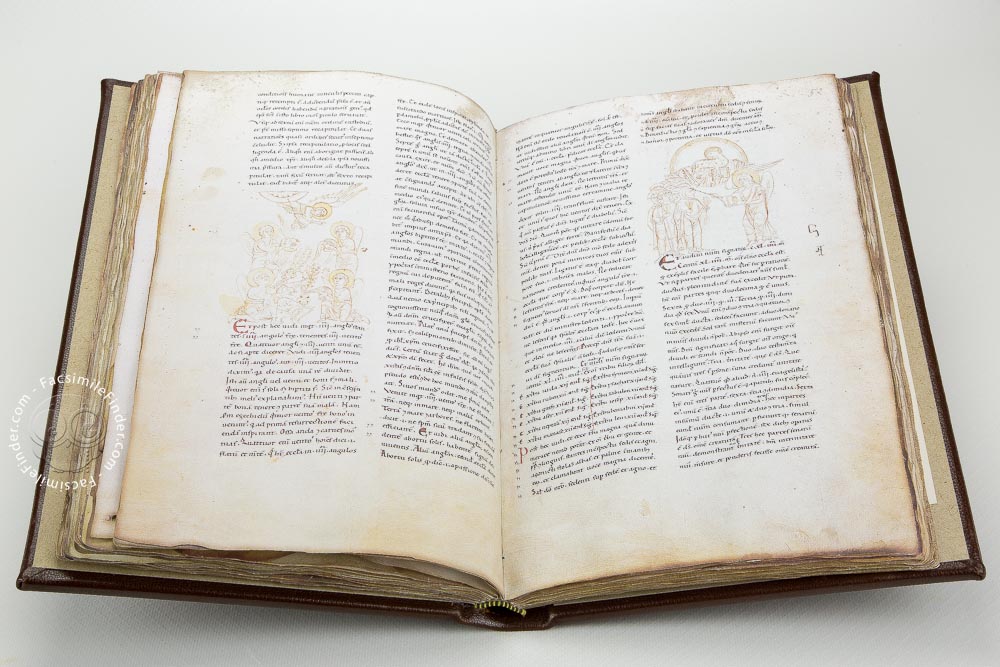

Moreover, its cycle of 55 illustrations generally does not correspond to the Beatus of Liébana iconography, but rather follows a tradition that was predominant in Central Europe during the Romanesque period. The Berlin codex was certainly made in Italy in the 12th century; however, its precise date and place of origin remain controversial.

A cycle of 55 illustration, not corresponding to the common Beatus of Liébana iconography

We also don’t know why a probably monastic library in Italy ordered a copy of an Apocalypse commentary whose tradition and influence were basically limited to the Iberian Peninsula. Hence, the Berlin Beatus codex poses many interesting and fascinating problems. Thus it is surprising that so far the Berlin Beatus of Liébana has received little scholarly attention.

Except for the fundamental study of the Beatus of Liébana manuscripts by Wilhelm Neuss, the Berlin codex has only been briefly discussed and described by Andreas Fingernagel in one of the manuscript catalogues of the Berlin Staatsbibliothek, and by John Williams in his Corpus of the illustrated Beatus manuscripts.

A manuscript with South Italian Beneventan influences

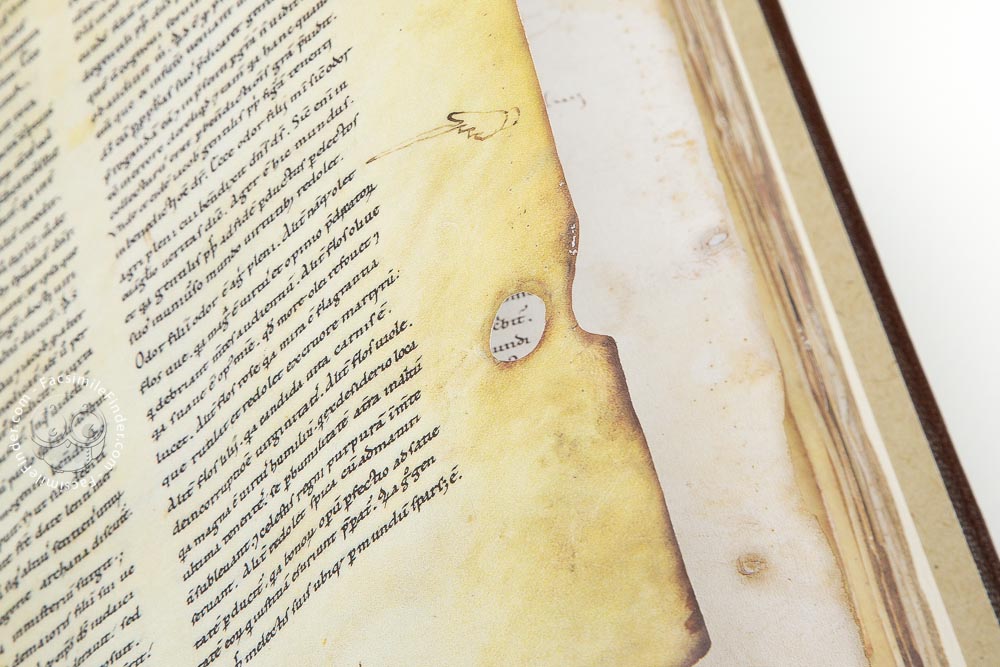

The Berlin Beatus of Liébana is a parchment codex of 98 folios. The folios normally measure 297 x 190 mm and must have been trimmed, at least at the lower margins, since part of the catchwords at the end of the gatherings are missing. The parchment of goat skin is not of high quality, with many holes and signs of wear.

Trimmed in the lower margins, folios are gathered in quaternions, with the exception of a quinio

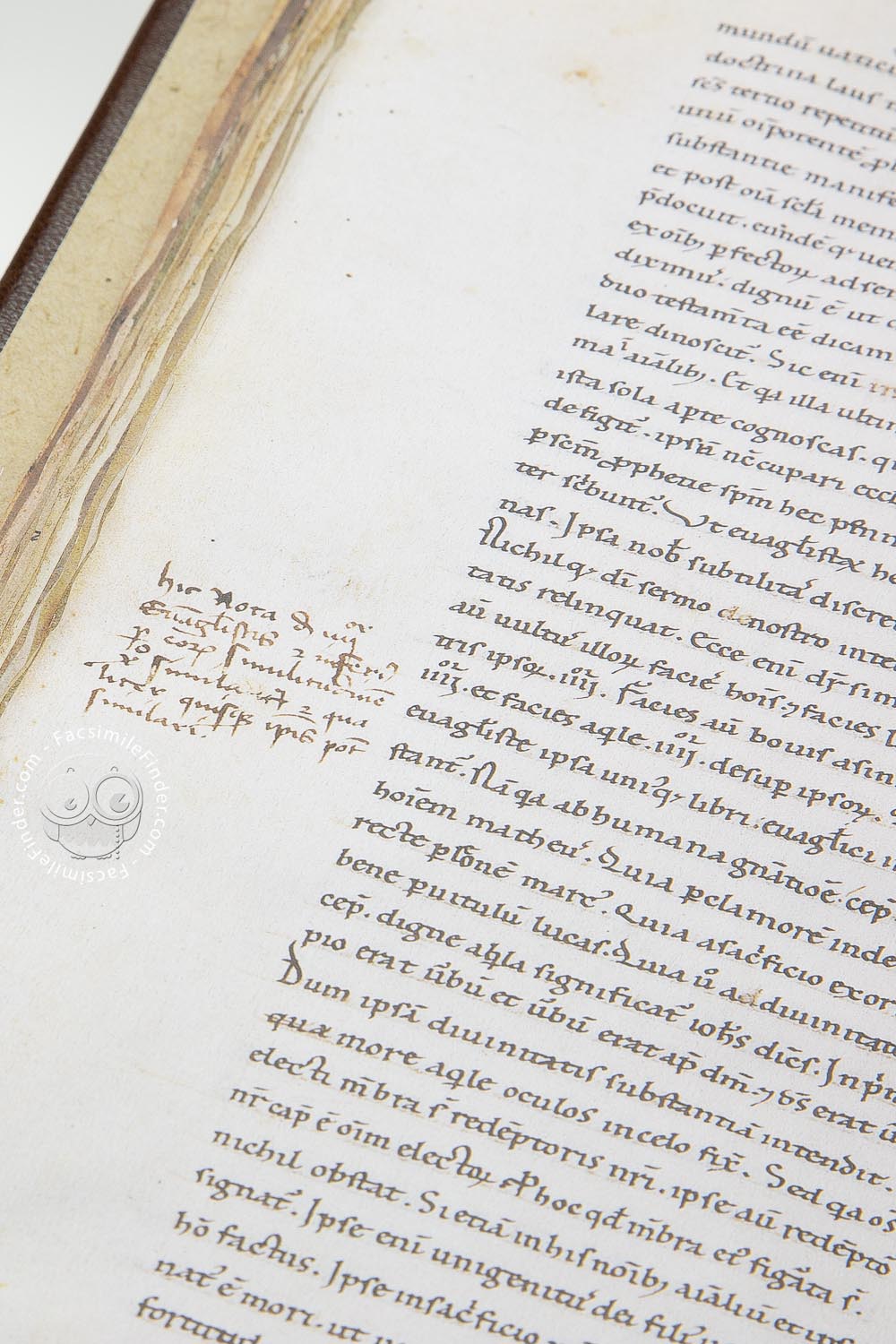

The text is written in double columns of 42 – 45 lines, in a Caroline or Romanesque script, with some influence of the South Italian Beneventan script. The nineteenth-century half-leather binding measures 310 x 198 mm, and on its spine carries the Italian title “Apocalisse con commenti e disegni a penna” (Apocalypse with commentary and pen drawings).

The codex has an older ink foliation in the right margin and a modern pencil foliation in the upper right corner. The gatherings are normally quaternios, i.e. quires composed of four double sheets of parchment folded in half to form eight leaves; the catchwords at the end of the gatherings appear in the lower margin. As an exception, folios 25 – 34 form a quinio, a gathering with ten leaves.

Content of the Beatus de Liébana, Berlin Codex

The text of the Berlin codex is limited to the Beatus commentary proper. It lacks all supplementary texts, such as the letter of dedication, the prologues, the Summa dicendorum (a kind of lengthy summary of the Beatus of Liébana commentary), the paragraph De Antichristo and the Antichrist Tables and, of course, all the supplementary texts which belong to the second family of the Beatus manuscripts which have the most recent, tenth-century edition of the commentary (since the text of the Berlin codex belongs to the older edition of the Beatus of Liébana manuscripts, the so-called Family I).

The Berlin Beatus of Liébana also lacks the passage on the time of the end of the world and the present time of the making of the manuscript, probably because the copyist of the Berlin codex found this passage theologically problematic; instead, he left part of the text column empty (fol. 52v). Nonetheless, the text includes the explanation of the precious stones of the Heavenly Jerusalem (Apoc. XXI, 18 – 20) which derives from the Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville (XVI, 7ff.), and which is illustrated in the other Beatus manuscripts, but not in the Berlin codex.

The Berlin Beatus, together with the Corsini, a copy at the Escorial, and the Vatican lat. 7621, form a subgroup of Beatus of Liébana manuscripts

There is also a confusion of the text sections between folios 33v and 37v, a confusion which recurs in the 12th-century Corsini Beatus (Rome, Biblioteca dell’Academia dei Lincei e Corsiniana, Ms. 40.E.6) as well as in two 16th-century copies in the Escorial (Biblioteca del Monasterio, cod. I.f.7) and the Vatican (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Cod. Vat. lat. 7621). With the latter two the Berlin codex also shares the incomplete end of the commentary (ending with the words “ita intelligendo”); therefore, these four manuscripts form a specific subgroup within the first family of the Beatus manuscripts.

Furthermore, in the Berlin Beatus of Liébana, the text of the commentary has been copied in a hasty and careless way, omitting nearly all of the chapter headings and often the paragraphs of the Apocalypse texts (called ‘storia’). This makes identifying a specific chapter or paragraph of the commentary very difficult.

A Beato of Liébana with no evident time and place

The Berlin Beatus of Liébana manuscript does not contain any reference to its time and place of origin. Hence, we have to rely on internal evidence, basically the paleography of the script and the style of one initial and the illustrations.

From the time scholars started to discuss the date and scriptorium, i.e. the place of origin, of this codex, there has been a consensus on two points:

- that the Berlin Beatus originated in Italy;

- that it has to be placed in the 12th century.

However, until today, there has been much disagreement about the precise date and place of origin.

Since the text critic Dom H. L. Ramsay had considered the underscript of the palimpsest on fols. 91 – 98 to be “Lombardic“, a nineteenth-century term for the Beneventan script, by a misunderstanding the theologian Wilhelm Neuss assumed a Lombardic, i.e. North Italian origin of the Berlin Beatus of Liébana. For decades this opinion was repeated by others scholars. The same applies to the paleographical dating of the script of the codex to the second half of the 12th century.

Recent discussion on the Beatus of Liébana in Berlin have suggested that the origin of the manuscript is Central Italy

However, these assumptions have been recently challenged on stylistic grounds, returning to arguments advanced in the 1930s by Albert Boeckler. On the basis of the decorated initial at the beginning of the codex and of the style of its illustrations, Boeckler had dated the Berlin Beatus in the first quarter of the 12th century or even around 1100, though he vascillated between the assumption of a South Italian or Central Italian origin, with Farfa as the probable scriptorium.

Beatus of Liébana - Berlin Codex, facsimile edition

A magnificent facsimile of the Berlin Beatus of Liébana is now available

View galleryConflicting views indicate that the question of time and place of origin is still controversial

In their recent discussion of the Berlin codex, both Andreas Fingernagel and John Williams have assumed that it had a Central Italian origin, expressing doubts regarding Farfa as its scriptorium; while Fingernagel also followed Boeckler in his early dating of the Berlin Beatus, Williams left the precise date open.

These conflicting or vacillating views indicate that the question of the time and place of origin of our manuscript still remains difficult and controversial, a question in which to some extent arguments of paleography stand against those of art history.

The German State Library, department of manuscripts owns the original manuscript of this Beatus facsimile.

The fine facsimile edition is published by Millennium Liber, Spain