Photography and digitalization made the greatest changes in the world of facsimiles. But what was the impact of technological advances in the facsimile making process? What kind of changes did they bring forth?

Here we are, back again for another dip in the past. This time we are approaching our years and the facsimiles get more and more perfect the closer we get to contemporary techniques. Let’s see what the Modern Era brought forth, and what the passage from analog to digital photography meant in creating a facsimile.

New 19th Century Methods and Opportunities

It was the invention of the chemically induced flat printing method of lithography, made by Alois Senefelder in Prague at the start of the 19th century, that first led to the beginning of continuity and an enormous upsurge in the art of making facsimiles.

These direct processes were the first to avail themselves of the water-repellent properties of fats and made approaches to the reproduction of halftones feasible. The lithography method, familiar to us today as an exclusively artistic technique, for its inventor and first users was a purely reproductive process.

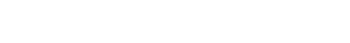

Therefore, it is no wonder that the first important work reproduced by this method was Dürer’s marginal drawings for the Prayer book of the Emperor Maximilian, today in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich. This edition appeared in Munich in 1807.

The Importance of Photography

However, the real revolution came with photography. Its copying technique, combined with various refined options for lithographic reproduction, eventually led to the collotype, a process invented by Alphonse Louis Poitevin in 1855. This first and oldest facsimile process made it possible to eliminate numerous elements of manual copying work.

The collotype’s reticulation, used in place of the familiar modern halftone dot, provided the ideal possibility of reproducing manuscripts as faithfully as possible well into the mid-20th century. Reproduction of pictures depended primarily on the photographic image, and subjective copying work was largely replaced by physicochemical objectivity.

It is barely possible to count all the facsimile editions that came into being thanks to this method during the 19th and 20th centuries and even as late as the period after the Second World War. The technique was used to its fullest throughout Europe to make old book treasures accessible and to preserve them. In 1899, the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, under Prefect Franz Ehrle, inaugurated its series Codices e Vaticanis Selecti.

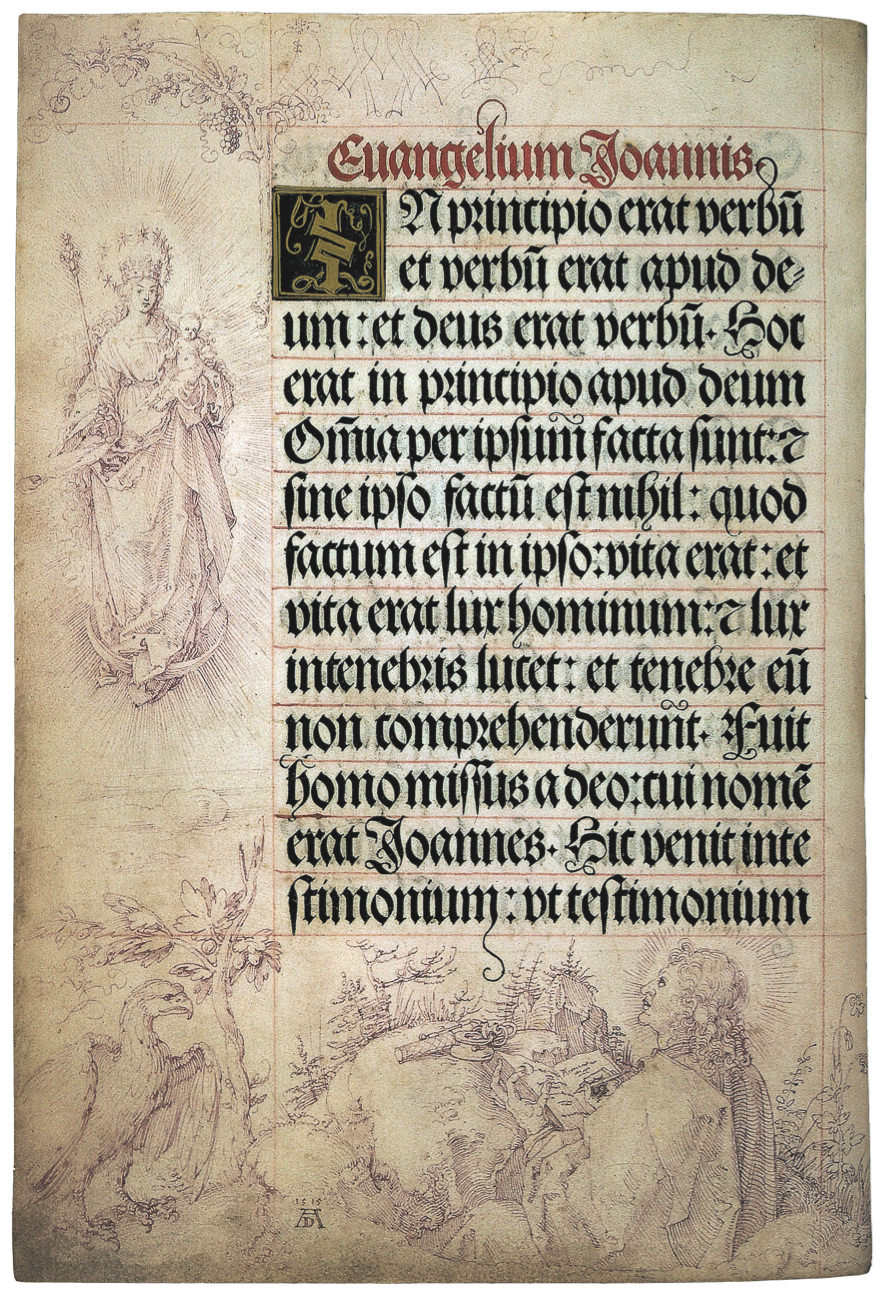

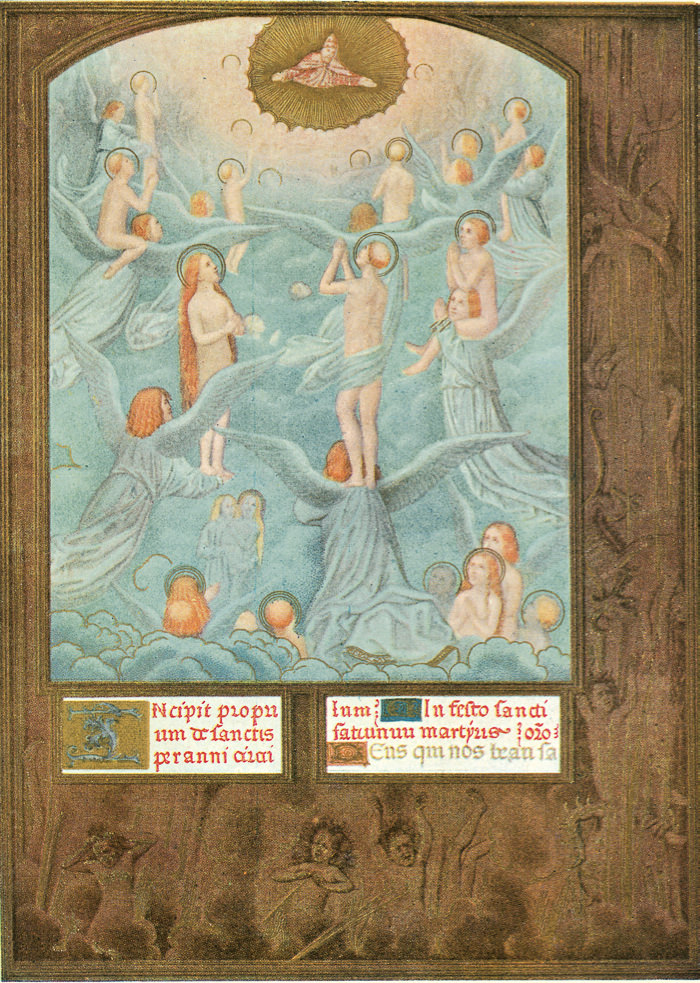

Still, even with collotype, the intervention by the lithographer (the term has persisted since the days of stone lithography) was still substantial, and went so far as having miniatures being forged. We need only recall the 1906 edition of the Breviarium Grimani (created circa 1510). In the reproduction, nude body parts, judged to be offensive, were masked with drapes of blue cloths, which in no way resembles the definition and the idea of the facsimile.

The Facsimile in Our Day

The decisive turning point in methods of creating facsimiles occurred eventually after the Second World War, when economic conditions in Europe permitted the bringing of the modern color printing techniques – regardless if copper gravure, letterpress or the modern flat screen printing methods, photoengraving and offset printing – to be used on the documentation of manuscripts as well.

The developments in the foremost production of large-format diapositives (Ektachromes) and the use of highly advanced reproduction cameras for creating color separations in pre-press to obtain clichés, copper gravure cylinders, photoengraving or offset mats, were decisive for reaching this turning point. Offset printing fulfilled the demands made regarding a facsimile edition, in which the first copy must look exactly like the last one of such a, most often limited, manuscript edition.

Finally, in the 1960s, triumphed the latest flat screen printing process, offset printing, that originated in America. When it came to color reproduction in the manuscript facsimiles making process, offset printing still faced competition due to letterpress printing. However, offset printing broke through, helped not only by the costs of the respective printing methods but also by the stability of printing color application. Soon, it fulfilled in the ideal fashion the demands made regarding a facsimile edition, in which the first copy must look exactly like the last one of such a, most often limited, manuscript edition.

The Advent of Digitalization

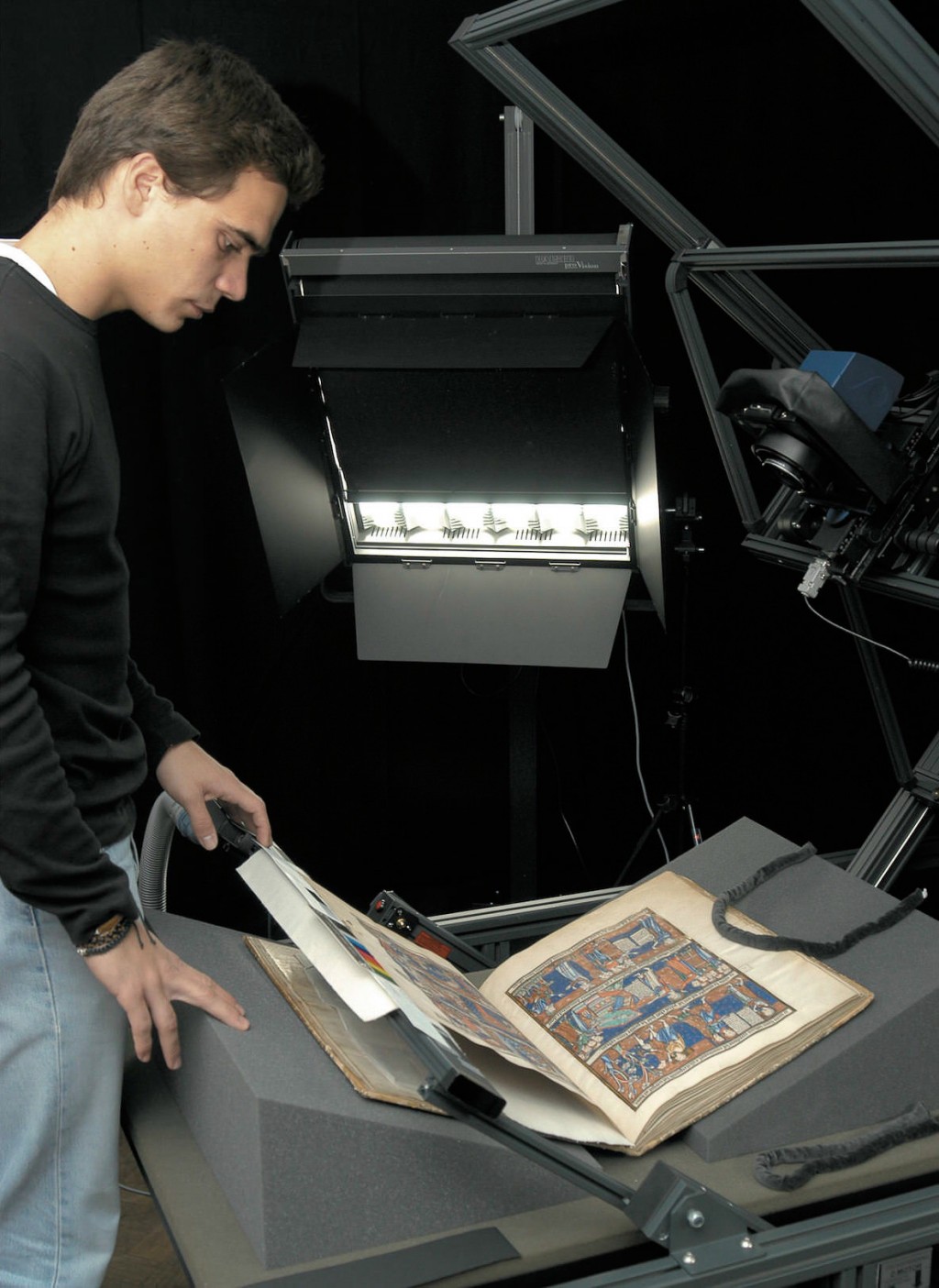

Another decisive development loomed during the second half of the 1970s, ultimately to prevail. The reproduction cameras up until then, in which the color separations, i.e., the films for the pre-press stage, were created, were replaced by repro scanners.

Since digitalization is also used for image data capture, i.e. in photographing the original, there are hardly any more obstacles that cannot be overcome in faithful color reproduction. This is not to impugn the quality of editions produced up until that point, for in the history of the color facsimile there existed editions that hold up against modern quality judgments, both during the years between the wars, and especially after 1960.

This is the case even when such manuscripts were selected for making a facsimile whose faithful reproduction could be guaranteed, given the technical means available in each case. Since digitalization is also used for image data capture there are hardly any more obstacles that cannot be overcome in faithful color reproduction.

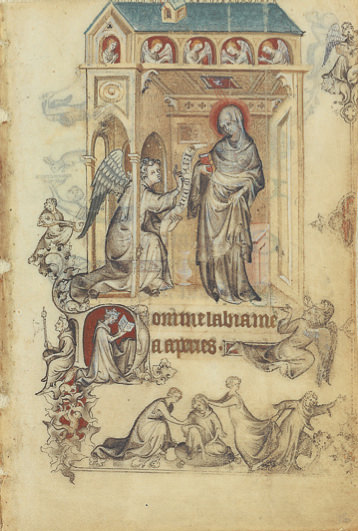

So, for example, the making of the facsimile of the Book of Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (The Cloisters), would not have been feasible prior to 1995. Today, there are no longer any limits to a perfect color reproduction and faithful tracing of all details. The facsimile, just like the original, can be inspected with the magnifying glass without missing anything.

But one thing still needs to be underlined at this point: we can only speak of a modern facsimile edition if a work of solid scholarly commentary accompanies the facsimile volume, to explain the codex in every aspect to the layman as well as to the scholarly specialist, as completely as possible and regardless of the discipline.

Conclusions

Thanks to modern techniques, and especially thanks to photography and digitalization, it is easier to produce copies of ancient manuscripts but this does not mean the process is without challenges. What do you think? Have you ever had the chance to admire a facsimile, or even an original manuscript? Let us know!

Coming Next..

- The Story of Faksimile Verlag, Publisher of Fine Facsimile Editions – part 1

- Facsimiles and the Role of Illuminated Manuscripts: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 2

- What is a Facsimile: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 3

- How it All Began: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 4

- From Analog to Digital: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 5

- The Making Process of a Facsimile: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 6

- Challenges and Magic of Facsimile Production: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 7

- Binding, Paper, and Commentary: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 8

- Treasures of the Past: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 9

- Gems of the Middle Ages: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 10

- Flemish, Burgundian, and Biblical Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 11

- Middle Ages through the Manuscripts: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 12

- The Challenges of Gothic Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 13

- Ottonian and Charlemagne’s Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 14

Subscribe to Our Newsletter