When we discovered the connection between a 15th-century astrology manuscript and a nearby humanist church, we wanted to see it for ourselves. Follow us on a trip to Renaissance Rimini!

“With none other than you could I speak more joyfully about the stars”, wrote the poet Basinio da Parma to his patron Sigismondo Malatesta in the opening verses of the poem Astronomicon. Inspired by ancient Greek knowledge of the cosmos, the work is regarded as the first Italian humanist poem to deal with the planets and stars and is dedicated to one of the most multifaceted leaders of 15th-century Italy.

Ruler of the Adriatic town of Rimini since his 13th year, Sigismondo went down in history for being at the same time a daring condottiere, poet, and patron of the arts – his fascination with classical antiquity and his ambition for personal acclaim left the city two imposing monuments, the fortified mansion Castel Sismondo and the Tempio Malatestiano, a pagan-inspired temple built on the ruins of a Christian church.

A bitter enemy of the Papal States, Sigismondo surrounded himself with the most gifted artists of his era – Leon Battista Alberti, Filippo Brunelleschi, and Piero della Francesca, to name a few – to foster artistic growth and make his dynasty immortal, a cultural plan the Tempio Malatestiano and Basinio’s Astronomicon were both part of.

This strange church is one of the earliest extant buildings in which the Neopaganism of the Renaissance showed itself in full force. – J. Addington Symonds

Born near Parma, Basinio studied at the courts of Mantua and Ferrara, whose libraries held copies of Aratus’ Phenomena, a didactic poem on constellations and weather signs composed between the 3rd and 4th centuries BC. Similarly, in his Astronomicon, Basinio gave an elegant description of the celestial sphere, zodiac and non-zodiac constellations, the motion of five planets and the effects of the sun and the moon.

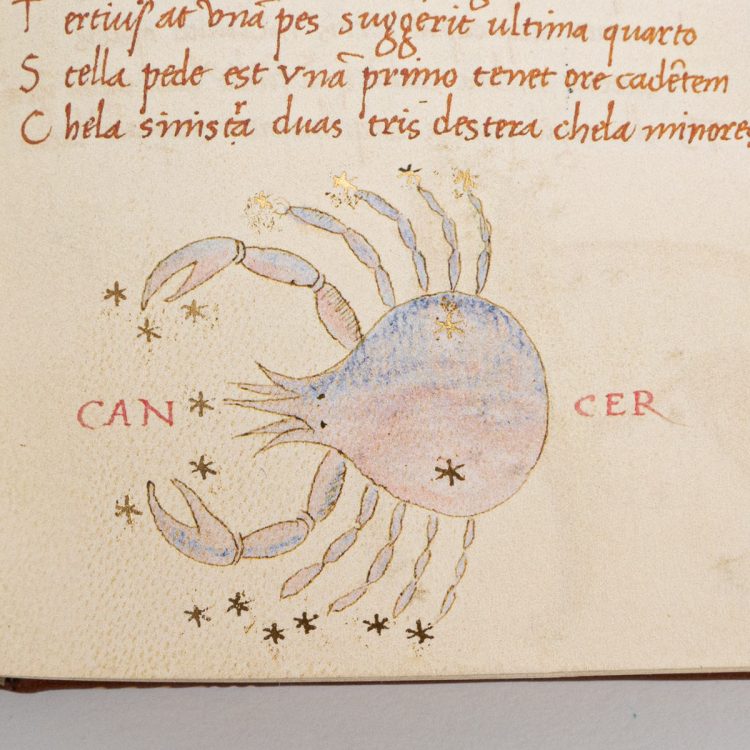

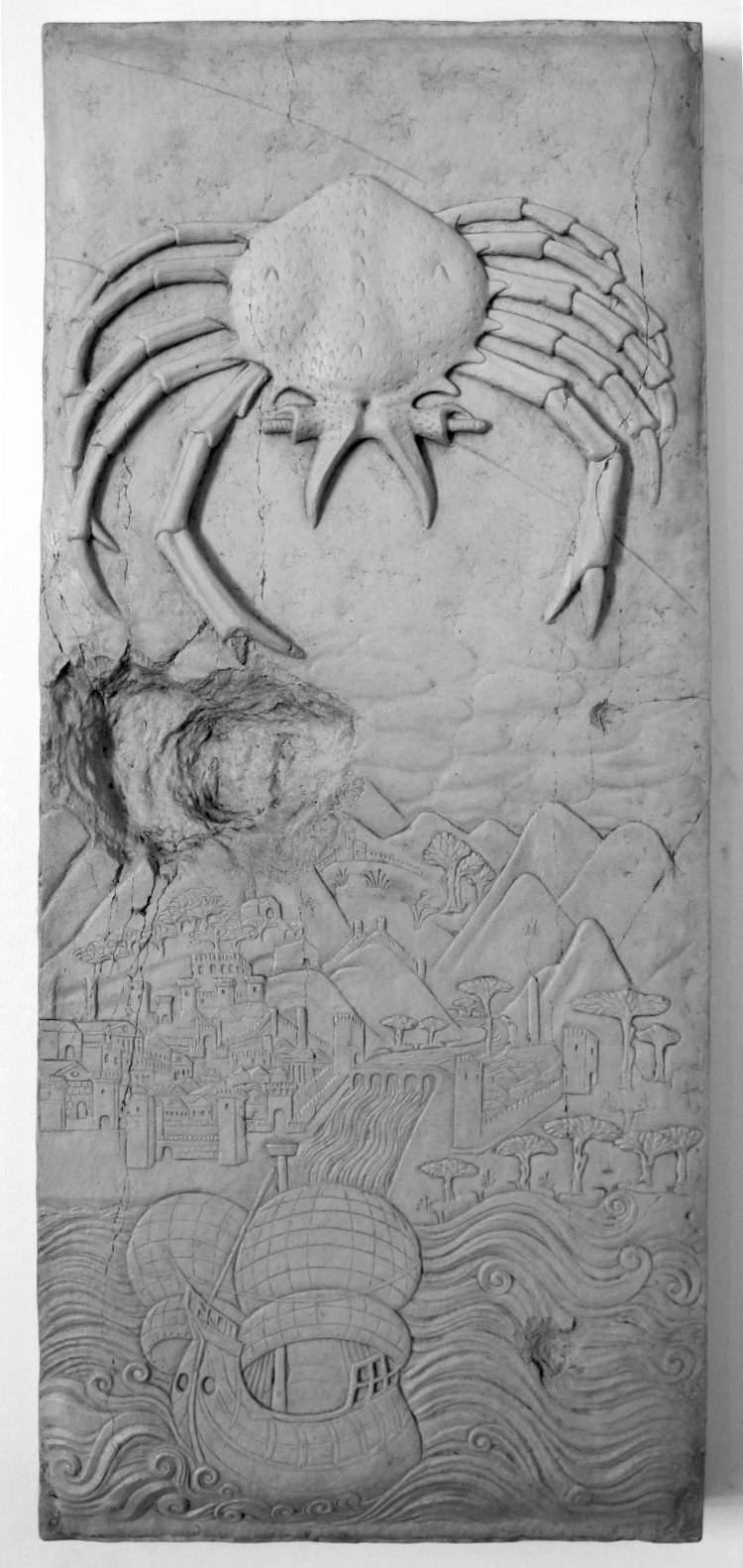

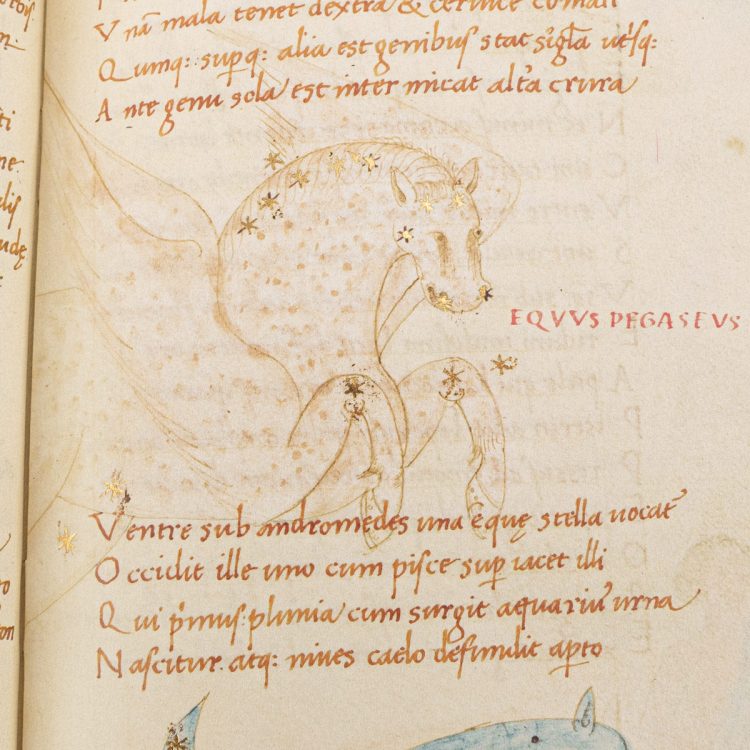

The hexameter poem features thirty-eight illustrations drawn in the so-called papyrus style, i.e. placed in the blank spaces of the text block. In each constellation, the stars are illuminated with gold and shine every time the page is turned. Basinio and his patron Sigismondo shared a passion for ancient Greek language and science – many of the constellations in the Astronomicon are also carved into the marble walls of the Tempio Malatestiano. According to scholars, Basinio da Parma himself chose some of the allegories for the church’s decoration.

Nothing but the fact that the church is dedicated to S. Francis, and that its outer shell of classic marble encases an old Gothic edifice, remains to remind us that it is a Christian place of worship. It has no sanctity, no spirit of piety. – J. Addington Symonds

When we found out about the deep connection between the manuscript we were leafing through and the main church of Rimini, a town just a few kilometers away, we decided to admire its marble reliefs with our own eyes.

It did not take us long to spot the constellations: in the right-hand nave, not far from the entrance, is the Cappella dello Zodiaco (Chapel of the Zodiac), also called Chapel of the Planets or Saint Jerome. One of the most stunning chapels of the building, it is rich in bas-reliefs attributed to the Renaissance sculptor Agostino di Duccio, portraying the planets and the signs of the zodiac. But what remained etched in our minds is the image of 15th-century Rimini, with its Roman bridge, fortified walls, harbor, and Sigismondo’s towering mansion in the background. Above the hills, guarding the town is a crab as big as the sun: it is Cancer, the zodiac sign of Sigismondo Malatesta.

When Basinio da Parma learned about his impending death in 1457, he left Sigismondo an epic poem in 13 volumes entitled Hesperis, an ancient Greek book containing the works of Homer and Apollonius, and asked him to be buried inside the Tempio Malatestiano. We saw his grave on our way out of the church and paid our respects to Basinio da Parma, a symbol of Italian humanism.

Greek Astrology throughout the centuries

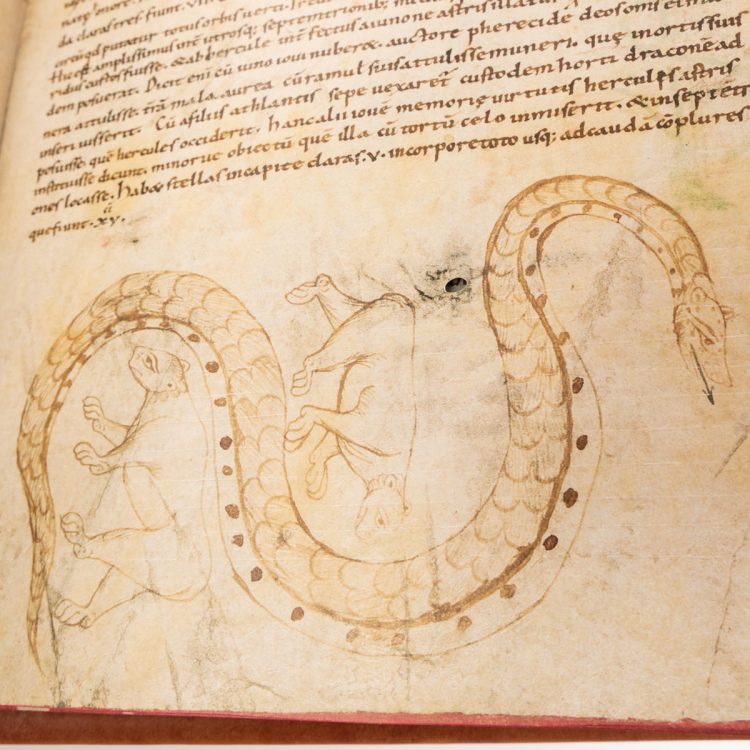

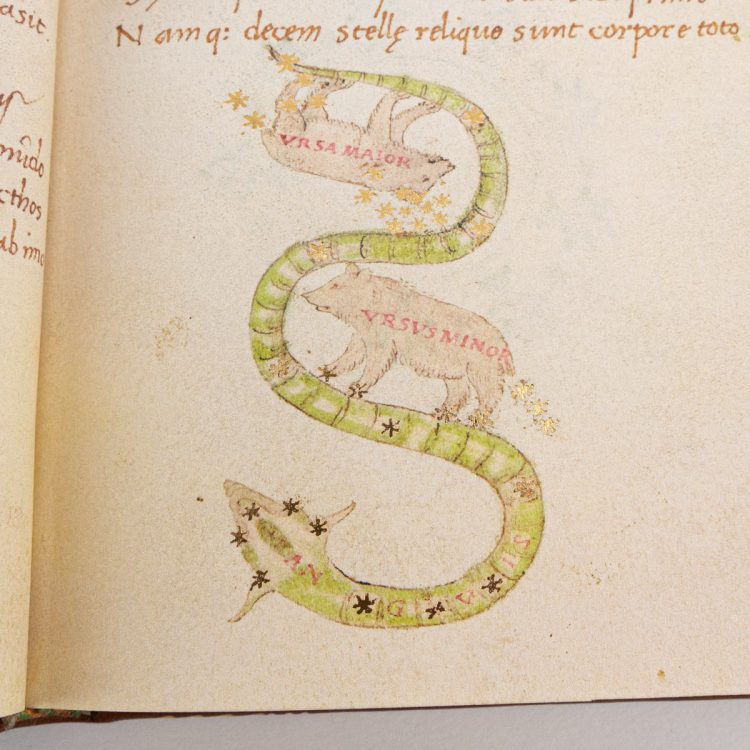

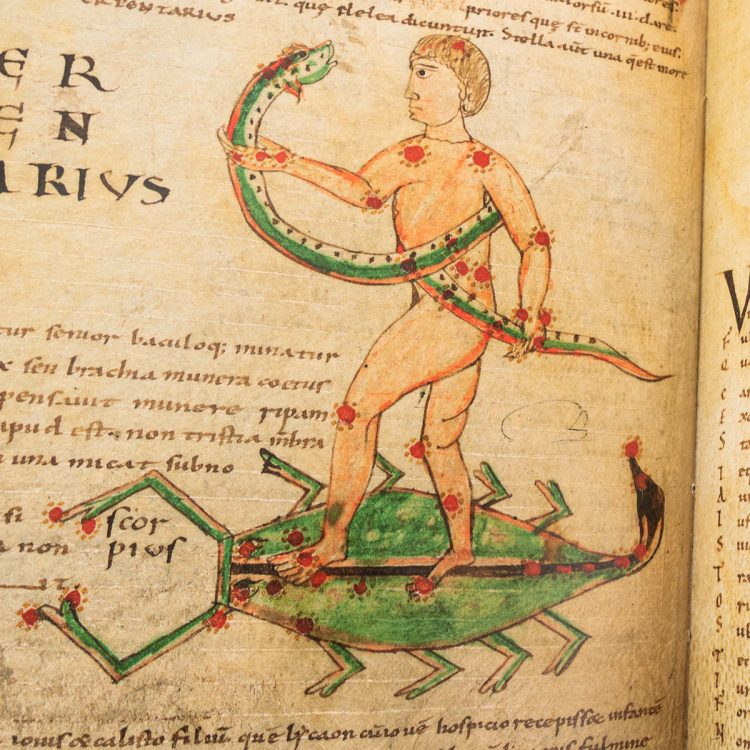

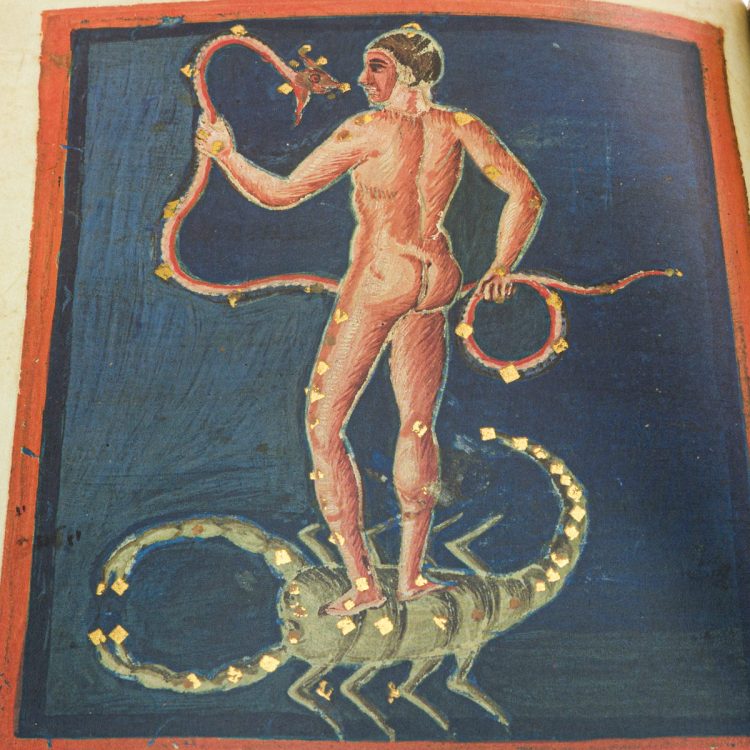

Aratus’ Phenomena inspired a wealth of literature, among which two Carolingian manuscripts known as Aratea and Aberystwyth Aratea, the former originating in 9th-century Aachen or Metz, the latter composed in France around the year 1000. By comparing the constellations in the Aratea, Aberystwyth Aratea, and Astronomicon, we can trace the changes in iconography over five centuries.

The Little Bear and the Great Bear

On either side the Axis ends in two Poles, but thereof the one is not seen, whereas the other faces us in the north high above the ocean. Encompassing it two Bears [Ursa Major and Minor] wheel together – wherefore they are also called the Wains. Now they ever hold their heads each toward the flank of the other, and are borne along always shoulder-wise, turned alternate on their shoulders.*

The winged divine horse Pegasus

Beneath Andromeda’s head is spread the huge Horse, touching her with his lower belly. One common star gleams on the Horse’s navel and the crown of her head. Three other separate stars, large and bright, at equal distance set on flank and shoulders, trace a square upon the Horse.*

The Scorpion

When the Sun scorches the Bow and the Wielder of the Bow, trust no longer in the night but put to shore in the evening. Of that season and that month let the rising of Scorpion at the close of night be a sign to thee. For verily his great Bow does the Bowman draw close by the Scorpion’s sting, and a little in front stands the Scorpion at his rising, but the Archer rises right after him.*

*Quote from Aratus’ Phenomena, translated by G.R. Mair.

Stay tuned for NEW FACSIMILES and news by publishers at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

We will be back soon!