Bona Sforza, widow of the Duke of Milan, commissioned a lavish book of hours in 1490 from Giovan Pietro Birago, a master of early Italian Renaissance illumination. It would not be completed for another thirty years by a master of Northern Renaissance painting, Gerard Horenbout. This makes the Sforza Hours a rare example of a book in which two separate workshops had a hand in its creation. This book is one of the last of its kind, for the age of the manuscript was ending due to the rise of the printing press.

It is also one of the earliest documented cases of art theft when pages of the unfinished work were stolen from Birago’s studio. All of this alone would make the Sforza Hours a remarkable piece, yet the pictures themselves are of the highest caliber of early Renaissance illumination.

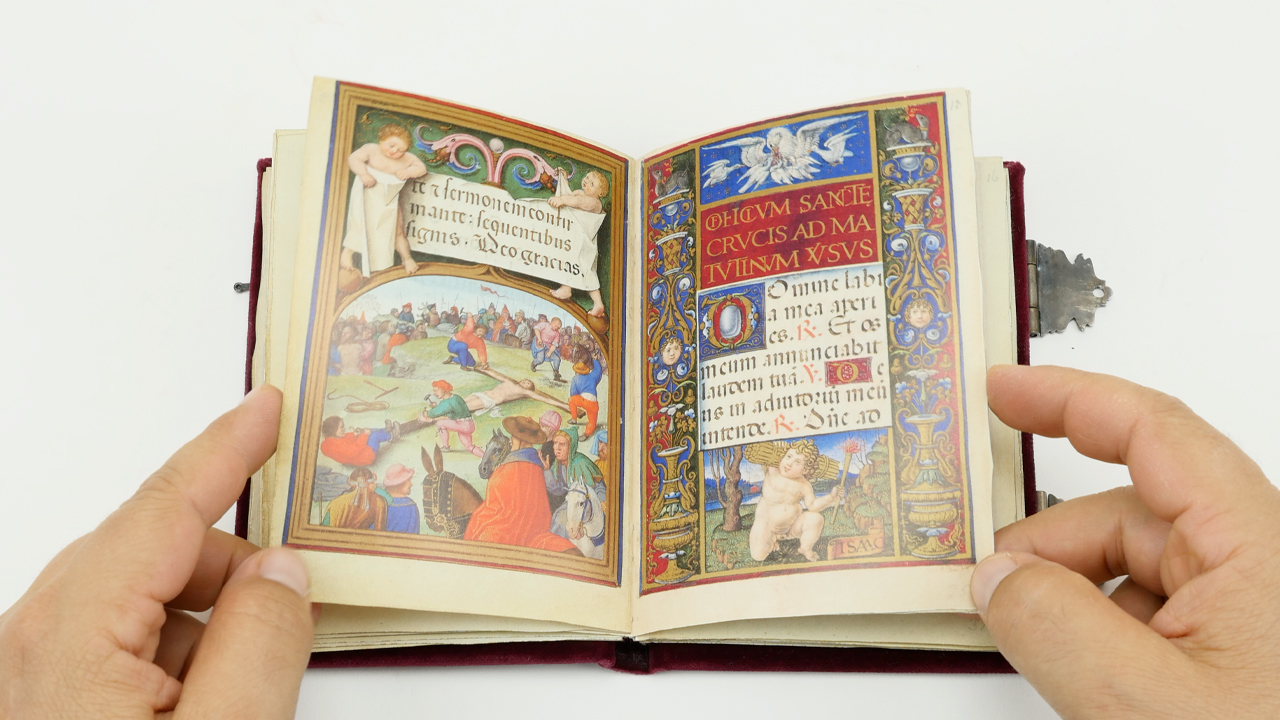

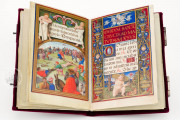

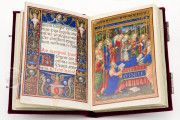

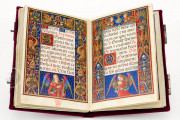

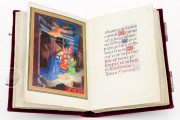

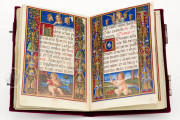

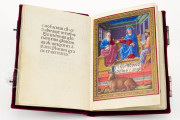

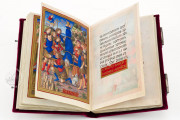

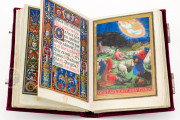

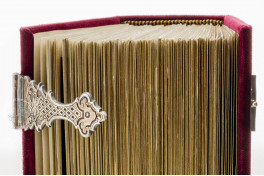

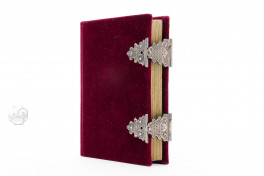

The text of the Sforza Hours is the Use of Rome in Latin written in black ink with rubrication over eleven lines in a single column. With sixty-four full-page miniatures, 140 text pages with decorative borders and numerous small miniatures and decorated capitals, the illustrative program is detailed and extensive, rich in vibrant colors and elegantly enhanced with gold.

A Pan-European Masterpiece

When Bona Sforza died in 1503, the book of hours she commissioned from Birago was left unfinished, in part due to the theft of some of its pages and in part due to familial estrangement. It eventually passed to Margaret of Austria who hired Etienne de Lale to complete the missing text after 1517 and Gerard Horenbout, later a court painter to Henry VIII of England, to complete the illuminations.

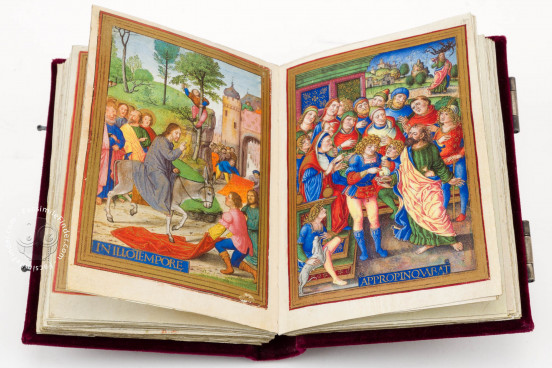

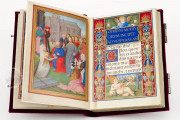

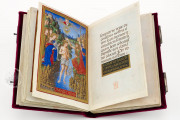

Horenbout was a master painter in Ghent and strove to match the Italianate style of Birago’s work for the sixteen additions he made to the manuscript. He included a portrait of his patron, Margaret of Austria, in the role of Elizabeth in the Visitation miniature.

A Renaissance Book of Hours

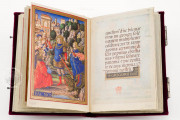

By the sixteenth century, the invention of the printing press had made books easier to produce and more affordable and the creation of handwritten books on parchment had once more become the domain of the elite. The Sforza Hours reflects this trend with its lavish, full-page images executed by masters in the field. The style of illustration also shifted. Rather than the staid Crucifixion iconography of the Middle Ages, Birago’s rendering is chaotic and disordered.

While the figure of Christ crucified rises centrally from the crowd beneath him, the figure of Mary is tucked into the middle ground with only her small halo separating her from the masses. Horenbout’s images have a calmer fantasy despite his efforts to copy the Italianate style.

Pages Stolen from Artist’s Workshop

In 1494, a friar stole a collection of pages from Birago’s commission for a book of hours from Bona Sforza. The stolen pages included the nearly completed calendar cycle. The pages were never recovered at the time and only recently resurfaced. Three of the stolen pages from the calendar resurfaced in the 1980s, two of which are also held in the British Library (Add. MS 80800 and Add. MS 62997) in addition to the image of the Adoration of the Magi (Add. MS 45722).

After Bona Sforza’s death, the unfinished manuscript passed to Duke Philibert III and after his death to his widow, Margaret of Austria. She completed the book and may have gifted it to Charles V and through him, it was taken to Spain where it was eventually purchased in 1871. It was presented to the British Museum in 1893.

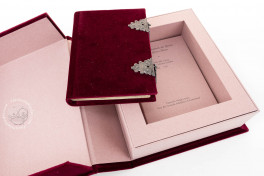

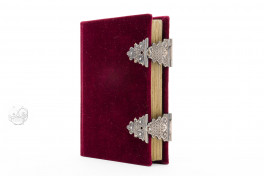

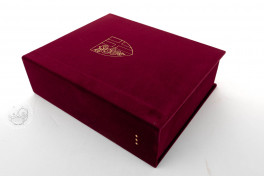

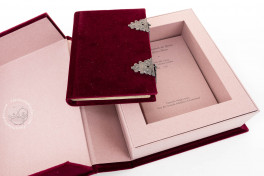

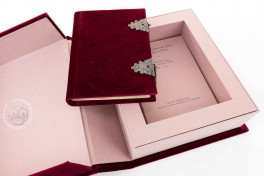

We have 6 facsimiles of the manuscript "Sforza Hours":

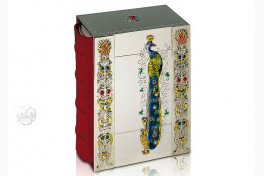

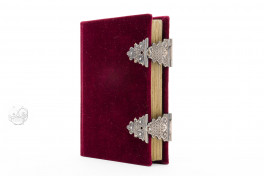

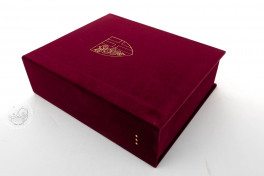

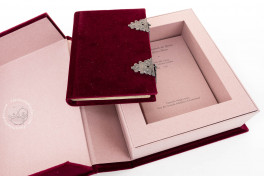

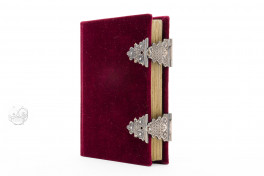

- Stundenbuch der Sforza (Complete Set of Four Volumes) facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag, 1993

- Stundenbuch der Sforza (Deluxe Edition) facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag, 1993

- Stundenbuch der Sforza (Standard Edition - Vol. 1) facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag, 1993

- Stundenbuch der Sforza (Standard Edition - Vol. 2) facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag, 1994

- Stundenbuch der Sforza (Standard Edition - Vol. 3) facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag, 1994

- Stundenbuch der Sforza (Standard Edition - Vol. 4) facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag, 1994